Living Stones

For these students, it's so much more than a pilgrimage

This story is part of a series covering Notre Dame’s presence in Jerusalem. All images and video were captured prior to the pandemic. The University is monitoring the global coronavirus situation with the hope of returning to normal study abroad programming when it is safe to do so.

If they were jet-lagged, they didn’t show it.

Just as the sun was rising on a Sunday in late July, a dozen Notre Dame undergraduate students filed into the lobby of the University of Notre Dame at Tantur. Less than 24 hours before, the members of the group had landed at Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion Airport. Today, they were embarking on a walking tour of Bethlehem. The highlight of the itinerary was clearly a visit to the Church of the Nativity, but it was evident from the outset this would be about more than a pilgrimage.

In this story

Hannah Hemphill Former Academic director of the Jerusalem Global Gateway

Hannah Hemphill Former Academic director of the Jerusalem Global Gateway Emilia McManus ’20 Political science major

Emilia McManus ’20 Political science major Analisa Pines ’21 American studies and Spanish major

Analisa Pines ’21 American studies and Spanish major Angie Appleby Purcell Notre Dame Global’s senior director for internationalization

Angie Appleby Purcell Notre Dame Global’s senior director for internationalization Rev. Russ McDougall, C.S.C. Former Tantur Ecumenical Institute rector

Rev. Russ McDougall, C.S.C. Former Tantur Ecumenical Institute rector

They filed out, walking through Tantur’s ample landscape, replete with olive trees, grape vines and a small but initially productive archaeological survey area, and through a steel gate at the edge of the property. Then down a narrow dirt road, to a wider, four-lane road, where on weekdays hundreds of Palestinians cross through the checkpoint and wait to catch the bus into Jerusalem. The students walked along the edge of the security wall, then through the checkpoint turnstile themselves, to get into Bethlehem.

The scenery changed dramatically. On the Palestinian side, graffiti covered much of the wall the height of an arm’s reach, much of it political in nature. You didn’t need to be able to read Arabic to get the message. In one scene, there was a depiction of a dove with an olive branch, a symbol of peace, yet the dove was wearing a flak jacket and had a target painted over its breast. It was perhaps the first sign many of the students had seen of the tension in the region. Perhaps it was not unexpected, but it certainly gave way to reflection.

St. Jerome famously said, “Five gospels record the life of Jesus. Four you will find in books and the one you will find in the land they call holy. Read the fifth gospel and the world of the four will open to you.”

And while it’s true that there is much to be learned and experienced here when it comes to faith and the life of Jesus, the University seeks to couple those incredibly important moments with attentiveness to the current complexities in the region.

“We started off the day in a deeply religious mindset, where we saw the place of the birth of Jesus. And as a Catholic that is one of the most important places you can go and feel as close as you can to God, and your faith.” —Emilia McManus

“It’s always a matter of remembering there’s a plethora of narratives,” said Hannah Hemphill, academic director at the Jerusalem Global Gateway. “So it’s looking at the itinerary and trying to strike a balance of the narratives.

“I consider it a job where my mandate is not just simply exposure to information, but its formation,” said Hemphill. “I see that as the mandate of Notre Dame. They take very seriously the pursuit of truth, the pursuit of justice, and I see that as translating very well into a program like this.”

The narratives in this three-week summer study program are provided by Hemphill, and also by various in-country guides. These scholars and nationals provide not only historical, but also present-day context.

Sometimes, they provide a twist on a familiar story. At the Church of the Nativity, the students’ guide, Kamal, ushered the group through the shrine of Jesus’ birth and into the neighboring Church of St. Catherine. A sign posted on the door reads, “If you enter here as a tourist, you would exit a pilgrim. If you enter as a pilgrim, you would exit as a holier one.”

Kamal led the group down a staircase into a series of caves. One of them is where St. Jerome translated the Bible into Latin. In an adjoining cave, Kamal gathered the group and offered an interpretation of the famous “no room in the inn” passage found in the Gospel of St. Luke. Kamal suggested the text implies that indeed Mary and Joseph found lodging, but the space was so cramped that there was in fact no room for a woman in labor. This, combined with the context of Jewish laws around cleanliness, made it likely that indeed the Holy Family moved from the spot currently marked with the shrine … to the space where the students currently were seated, in the cave beneath the Church of St. Catherine. To mark the occasion of their presence in Bethlehem, at least very near the spot venerated as the place where Jesus was born, Kamal led the group in singing “Silent Night.”

It wouldn’t be the last alternate viewpoint presented that day. After a stop in the Mosque of Omar and Bethlehem’s “souk” (the city’s marketplace — one sensed it hasn’t changed an awful lot since the biblical era), one of the students offered some thoughts on the experience.

“I think we saw two narratives,” said Emilia McManus ’20, a political science major and peace studies minor who is eyeing a career in international peace building. “We started off the day in a deeply religious mindset, where we saw the place of the birth of Jesus. And as a Catholic that is one of the most important places you can go and feel as close as you can to God, and your faith.

“And then we were reminded later in the day, as we came out of the church and as we spoke with our tour guide, who was a Palestinian, that there are people that still live here. So while the area is deep in history, deep in legacy and tradition, there is still strife in the region because of political struggles.”

The intermixing of moments of spiritual and personal reflection, and moments of jarring, evocative reality, typifies the course. That’s part of the intricacy of the Holy Land: It is of singular significance to the three Abrahamic religions, and that layering is evident throughout. But woven into that is a territorial and political conflict that many have heard about, but relative few have observed up close. Perhaps no other place put the geopolitical dynamic in focus more clearly for the group than the visit to Hebron.

“We were not prepared for that,” said Analisa Pines ’21. “All I knew was that it was a Muslim city that had a lot of historical significance in Islam, but did not know much more. We knew there was a (Jewish) settlement there, but I didn’t really know what that meant or what that would look like.

“Just walking through the streets, they’re all covered by netting, because the settlers will often throw things at the Palestinians. … It was really eye-opening to see that firsthand.

“There was a point where we got to walk into the settlement, and we had to leave our tour guide behind because he’s not allowed in,” Pines said.

“As outsiders, not even from this land, we could travel wherever we wanted,” McManus remembered. “As a Palestinian tour guide, he was restricted in certain places. He’d stop at certain checkpoints and say, ‘You guys go ahead; I have to wait here.’”

There were moments of optimism too, the students said. McManus pointed to the “dual-narrative tour,” during which a Palestinian and Israeli took the students to various sites, explaining the significance of each location from their respective points of view. Somewhat predictably, the guides pushed each other verbally and disagreed passionately at times. But for McManus, it was a small indication that coexistence can be achieved.

For Pines, sharing meals with Palestinian and Israeli families on each side of the security wall showed something similar: that despite the very real struggle and tension in the region, many families simply try to carry on with the normal rhythm of life. While these families were separated in a forceful way physically, the gap in geography and perhaps in values was not quite as imposing. And for Pines, whose father is Jewish and mother is Catholic, it was a chance for a new Shabbat experience.

The Old City

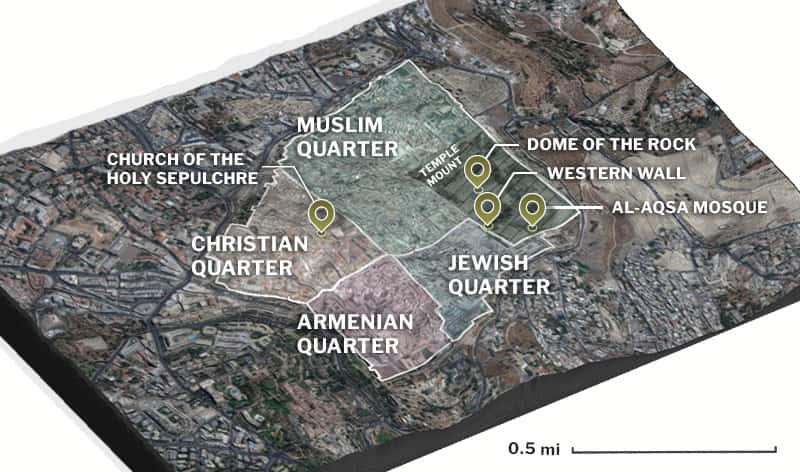

The Old City is divided into four quarters named for the ethnic or religious identity of most of the people who live in them. The Old City is small, measuring roughly a square kilometer. Yet approximately 40,000 people live here, 27,000 of them Muslim. The current walls around the Old City were built by the sultan Suleiman in the 16th century. Editor’s note: We recognize any map of this region is open to interpretation based on differing perspectives. The maps in this series are meant to be representational, not an endorsement of any of those perspectives.

Editor’s note: We recognize any map of this region is open to interpretation based on differing perspectives. The maps in this series are meant to be representational, not an endorsement of any of those perspectives.

“I thought I knew all about Shabbat, but it was not like my Shabbat,” she said. “There were prayers I didn’t know, some things that were unusual. But eating dinner with both of those families was a really cool insight into the different cultures that you’re not necessarily seeing when you’re getting the tours and hearing the history.”

Yet even the tours in the summer study course offer quite a bit more than just a walk by landmarks. In one particular morning in the Old City, students experienced the Jewish Quarter with their guide, Hannah.

“One of my favorite days on the trip we sat for maybe two hours as our guide pointed out the different ways Jews were dressed and the things they were eating and doing. It showed where they were on a spectrum of observant Judaism,” Pines said.

“I thought I had a lot of knowledge of Jewish history, but it showed me I didn’t,” she said.

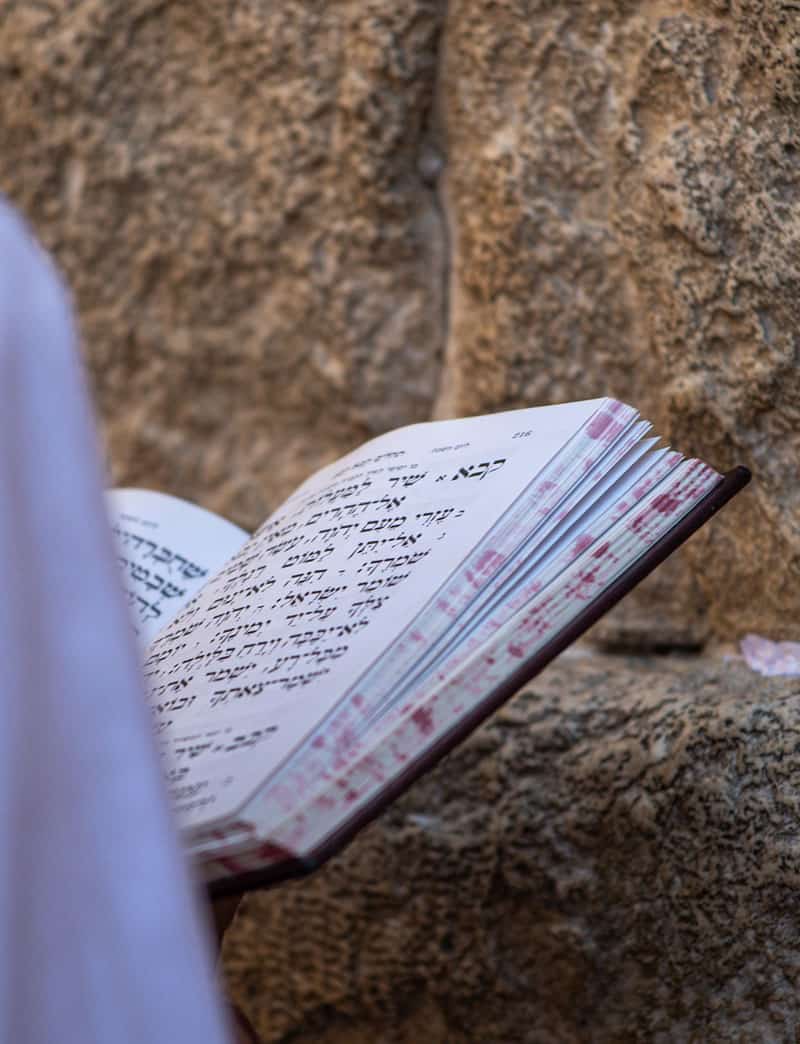

However, there was one spot in the Old City with which Pines was familiar: the Western Wall, one of the holiest sites in Judaism. It was the final stop for the group during the morning in the Jewish Quarter. The students joined throngs of pilgrims and tourists at the site, the remaining piece of the Second Temple. The wall itself formed the western edge of the support structure for the Temple Mount, which today holds the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque, controlled by Muslims. Jews returned to prayer here for the first time in centuries after the Six-Day War in 1967. Pines had heard a lot about the site throughout her life, and discussed the opportunity to go there during the trip with her father.

“My dad actually started crying,” she said. “He told me it would be really meaningful if I could put a prayer for our family in it, and so I did. I got choked up.”

The Old City is a wonder unto itself. It covers only about a square mile of land, with a population of approximately 40,000 people, more than half of whom are Muslim. The winding streets are layered on each side with shops no larger than a one-car garage, selling everything from pottery to spices to touristy garb. (One shop even had the Notre Dame monogram emblazoned on a T-shirt with Hebrew lettering.) You walk through these streets and you can’t help but to feel in the world. The history and the significance hit you immediately after entering one of the gates, along with the diversity of sight, sound, smell and language. The wonder and charm of the Old City comes not just from being home to holy places, but also from maintaining a sort of immunity to time that makes it much easier to imagine those sites in their contemporary context.

On the opposite side of the Old City from the Western Wall is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, venerated as the site of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial. Some students went there early one morning, before the crowds arrived. A group of Korean pilgrims was celebrating Mass at the time. The morning light shone through the windows and bounced off the hundreds of lamps and chandeliers, brass statues and icons, and coated the shrine at the spot of the crucifixion in a glowing white brilliance. Down a flight of steps and across the main hall stands the shrine of Jesus’ tomb. A monk was holding vigil at the head of the shrine. McManus struck up a conversation with him.

Site of Christ’s Tomb

In the first century, this site was a small abandoned quarry just outside the city walls. Archaeologists have confirmed it was the site of a Jewish cemetery at that time, with tombs cut into the rock face. Scholars have pointed to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as a likely spot for Jesus' crucifixion and burial, based on biblical and extra-biblical sources. This graphic shows the first-century topography and how the current Church is situated in that context.“They have some … not conflicting, but differing ways of honoring where Jesus was buried,” she said. “We saw on the back end of the shrine a location of a stone, and that’s where it’s believed Jesus’ head was laid, so there’s a whole shrine dedicated to that spot.

“Ecumenism is one area, theology is another, but our role as an institution of learning is to engage all disciplines the University has to offer.” —Angie Appleby Purcell

“It’s fascinating. I was expecting to see the interplay of the three Abrahamic faiths, but to see divisions or at least different interpretations (among Christians) of the way that Jesus was crucified and buried helps you reflect more on your own faith.”

Which is a reminder of why the University began its presence here in the first place.

“I am encouraged and inspired by that early mandate,” said Angie Appleby Purcell, the senior director for internationalization in Notre Dame Global. “We are a university engaging and advancing scholarship, research, and inquiry on all levels. Ecumenism is one area, theology is another, but our role as an institution of learning is to engage all disciplines the University has to offer.

“Father Ted [Hesburgh] said, ‘A university is a place where the Church can do its thinking.’ And Tantur is a prime example of how that’s playing itself out, and still does.”

“Tantur is a place that has brought scholars and students and committed lay people and clergy from all over the world,” added Father Russ McDougall, C.S.C., rector of Tantur Ecumenical Institute. “And by sending its own students here, by having Notre Dame faculty come here for their own research, they have engaged with all of those people who’ve come from different parts of the world.”

The students are coming to Tantur in increasing numbers. The study abroad program is more popular than ever, with enrollment increasing by almost a third over last year. The program was initially offered only in the spring; now there is a fall semester offering as well as the summer program, which Pines and McManus completed. In each, students are afforded the opportunity to experience much of the breadth of region: from Galilee, to Tel Aviv, to Petra in Jordan, and of course Jerusalem. Moreover, the program includes classes at partner institutions in the region like Hebrew University and Bethlehem University.

“By sending its own students here, by having Notre Dame faculty come here for their own research, they have engaged with all of those people who’ve come from different parts of the world.” —Rev. Russ McDougall, C.S.C.

“The undergraduates are exposed in ways that root them more deeply in the local context than perhaps some other study abroad opportunities,” said Appleby Purcell. “Immersive experiences are a part of the curriculum and the students can’t help but be exposed to a lot of things in an area of the world that for most of them is brand-new.”

But with that exposure comes a need to strike a balance, and with that, an opportunity to impart learning that goes beyond factual recall and imbues a pilgrimage to commemorate the events of the past, with a reminder of the present.

“Our professor Hannah (Hemphill) had a great saying,” said McManus. “She said a lot of people come to the Holy Land expecting to see the sites on a pilgrimage. But while they see the old stones, they miss the living stones, the people who are living here today. That really stuck out to me, because there’s more going on here than just the religious significance.”