Face to Face

Community-based classes help students learn Spanish

Pilo Bueno Jr. grew up as a migrant farm worker traveling around the country, following the harvests in a circle that started in Texas, went through the Carolinas and Indiana, and ended in Michigan or Colorado. Then it repeated, nonstop.

He was born in South Bend when his parents and their older kids had jobs picking tomatoes in Michigan. The family of eight traveled in one car. Between all the work and the constant moves, Bueno dropped out of school in fifth grade.

“We never had a home; home was where the next crop was,” Bueno said. “It was hard. My knees were always dirty and the fertilizer would turn our hands green. People would look at us funny and not want to touch us.”

He eventually ran away at age 16, drifting into manufacturing and truck driving before returning to South Bend and working his way up in auto repair. He earned a GED and business degree later in life and opened his own auto body and sales shop in Mishawaka. His parents finally stopped traveling and settled nearby.

The Buenos’ rich family story unfolds in Spanish over the course of several weekly meetings with two Notre Dame students at El Campito, a west-side nonprofit preschool and childhood development center. Bueno is one of many in his own family and others sharing their stories with students in Associate Teaching Professor Tatiana Botero’s community-based learning (CBL) class, “Immigration and the Construction of Memory.”

“Students get to learn these complex stories of immigration and family,” Botero said. “Learning the issues firsthand can be a real eye-opener to Notre Dame students. Their final reflections on getting to know the families are really powerful.”

Student Marc Philippon wrote that interviewing immigrant families “brought the class material to life,” while the project helped celebrate their journey to create a new life for themselves.

“The information I learned in this class provided me with entirely new knowledge about an issue that I had known little about before,” Philippon wrote. “But more significantly, it left me with a sense of discomfort on the current state of many immigrants in this country and a strong desire to shed light on the injustice they face and be a voice for them.”

While there are more than 200 community-based classes across Notre Dame, few faculty members have jumped in with more commitment than those in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, especially those teaching Spanish. CBL classes engage in a sustained partnership with community centers and schools through service or educational activities relevant to coursework. Spanish students in these classes average about 1,500 hours of service per year in South Bend.

Botero’s 13 students met in groups with several generations of bilingual or Spanish-speaking families to produce a book in Spanish laying out their story in writing and pictures. Elena Mangione-Lora’s class in Spanish translation worked with Holy Cross Elementary School to provide translation services for Spanish-speaking families at financial and reading literacy nights that the school offers.

The Romance languages department began experimenting in the CBL format about a decade ago when Marisel Moreno, an associate professor of Latina/o literature, took her classes to volunteer and speak Spanish at La Casa de Amistad, a west-side youth community center. Moreno discovered that live interaction with native Spanish speakers transformed learning the language from theoretical to real and inspired greater effort and cross-cultural understanding.

The department now offers six or seven CBL classes each year and even hired a director, Rachel Rivers Parroquín, who has a dual appointment in the Center for Social Concerns. Parroquín teaches a Latino children’s literature CBL course and facilitates the partnerships between community organizations and a half-dozen Notre Dame Spanish instructors.

“It’s not that students don’t want to study literature, but they want to see a practical application and practice their skills,” Parroquín said.

Mangione-Lora partnered with Holy Cross last year when Notre Dame’s Alliance for Catholic Education (ACE) began a Spanish immersion pilot program there. The west-side grade school had seen declining enrollment for a decade as the neighborhood changed from largely Polish to black and Latino.

Katy Lichon, director of the English as a New Language program in ACE’s Catholic School Advantage campaign, said Holy Cross called her while she was working with the Institute for Latino Studies on a program feasibility study. What was once the diocese’s largest grade school, with about 1,000 students, was looking for innovative ways to stay afloat.

“We had already been thinking about the changing demographic of the Catholic Church, and the need for programs that honor the language and culture of our diverse children and families,” Lichon said.

The immersion program, started in 2017 with pre-K, is taught 90 percent in Spanish at first and moves over the years to half and half. By adding a second class in addition to the traditional English one, school enrollment grew about 30 percent and should keep rising as the program moves up a grade each year. Lichon showed her support by enrolling her daughter, Mary Francis.

“There’s a wait list for these classes, just exciting things that are happening,” she said.

Last year, Mangione-Lora’s CBL class helped the new immersion program get off the ground by translating startup materials for the families: introduction videos, pickup procedures, registration forms, handbooks and disciplinary procedures.

This year, her class translated for Spanish-speaking families at after-school events that promoted educational literacy. In mid-April, the Notre Dame students sat in the Holy Cross cafeteria with three families to translate a presentation about building a diverse home library that promotes youth reading.

“Our role is to support the presenters,” Mangione-Lora said. “The students don’t just translate the presentation. They also prepare a specific glossary of terms used in the topic. And they decided to have two translators at each table rather than one up front, because we found the English speakers zoned out during the translations, and it created separation and tension.”

The students not translating recorded the presentations to create their own written translations, which were later reviewed in class to evaluate different word and meaning choices. Several students lingered after the presentations to talk more with the families.

Mangione-Lora said the challenge of the CBL format is that the teachers must be flexible and give up much of their control. She never knows exactly who in the community will show up. “It’s like planning a wedding and not knowing who’s coming,” she said.

Yet she and Botero both said the advantages of personal interaction with Spanish speakers easily outweigh the logistical difficulties.

Students are warned at the beginning that they should expect to put in extra time and adjust their schedules for the regular visits. Botero requires her students to get a CITI certification in responsible human research before the class even starts. The people the students meet often come from such different backgrounds that the training helps to bridge the gap.

For instance, one student group learned the story of Claudia Ramirez and her extended family of two sisters, two daughters, three grandkids and even her ex-husband. Ramirez said she left San Luis Potosí in Mexico to visit the United States for the first time in 1981, obtaining a visa to attend a friend’s wedding in Houston.

But she had her purse snatched at a bowling alley and lost all her money and identification. Just to go home, she had to take a job for two months at a hotel. But the experience got Ramirez thinking. “I saw the schools, and decided I’d love for my kids to have these opportunities,” said Ramirez, who like Bueno is bilingual.

After about six months back in Mexico, she decided to join an uncle in Miami but found few jobs there outside of farm work and restaurants. In 1986, she moved to South Bend, where an aunt lived, and worked dozens of different jobs over the years, usually two or three at once. She managed to land a job at Notre Dame that helped her put her kids through college.

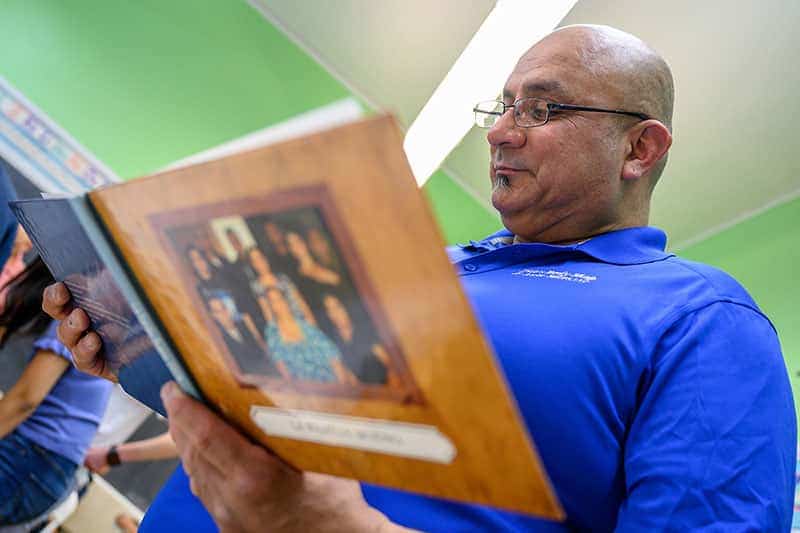

On a late April day at El Campito, the student groups presented their semester-long projects to the families, who brought traditional Mexican dishes for a communal dinner. The students read cards in Spanish thanking the families for their participation and patience.

The families crowded around the history books, pointing and laughing at pictures and stories based on hours of interviews. They ask the students questions, like how they created a visual family-tree genealogy. Botero and Parroquín said this bonding is one of their favorite parts of CBL classes.

Ramirez’s grandkids go to preschool at El Campito, which is in the building where her children went to the former St. Stephen’s School. That’s how she heard about the class offering to turn their oral history into a family memento.

“Being here and this process brought back a lot of memories,” Ramirez said. “The students make a big effort to speak Spanish. They learn from us and we learn from them.”