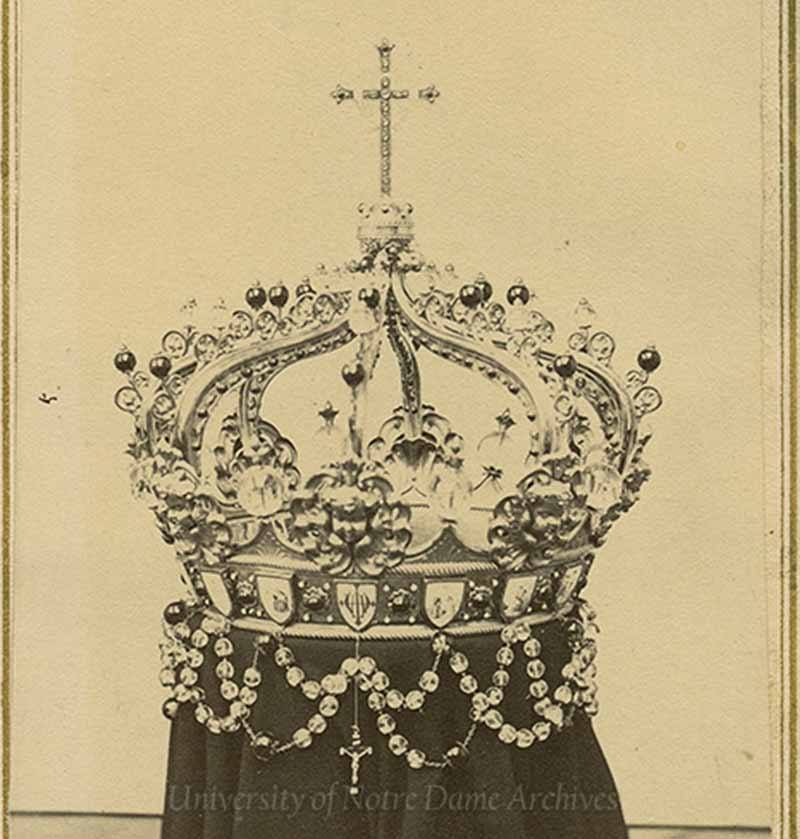

For years, it’s been the subject of fascination and inquiry for visitors to the Main Building (Golden Dome): a large crown, much too large for a human head, in a display case by the elevators. A plaque inside the case tells some of the story, but there’s much more to know about this University treasure...and another tiara that remains at the center of campus intrigue.

Origin Story

Notre Dame’s French founder loved being an American.

Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., literally kissed the ground when he arrived from France. When the first University commencement exercises were held on July 4, 1845, Father Sorin invited the South Bend community onto campus for festivities that included a reading of the Declaration of Independence, patriotic songs and a play. It became a local tradition to celebrate Independence Day at Notre Dame.

Father Sorin named Washington Hall after the American founding father he most admired. When the Civil War broke out, he dispatched seven priests from his fledgling University —more than he could reasonably spare — to serve as chaplains in the Union army. Suffice to say, Father Sorin’s embrace of the United States was full and unquestioned.

Yet Father Sorin’s French roots ran deep, if only by necessity. He took 42 transatlantic trips after founding Notre Dame, often to France to raise money and awareness for the University. The University’s connections to France remained strong and steadfast in those early decades, and in turn, the notoriety in that country of a small Catholic school in the American west began to rise, even in the highest levels of French society. Father Sorin was close friends with French emperor Napoleon III.

This was the context in which Rev. Joseph Carrier, C.S.C., was dispatched on a mission to France in 1866. Father Carrier, French-born and not long removed from his deployment as chaplain with the army of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, was a pioneer in science education at Notre Dame. His objective on this trip was to acquire specimens for the University museum, as well as lab equipment. He was apparently quite successful, procuring more than 50 boxes of supplies and a large telescope, a gift of the emperor. Father Carrier even secured an audience with Napoleon III, whose support for Notre Dame was rooted not just in his personal relationship with Father Sorin, but also in a desire to establish an outpost of French culture in the American frontier.

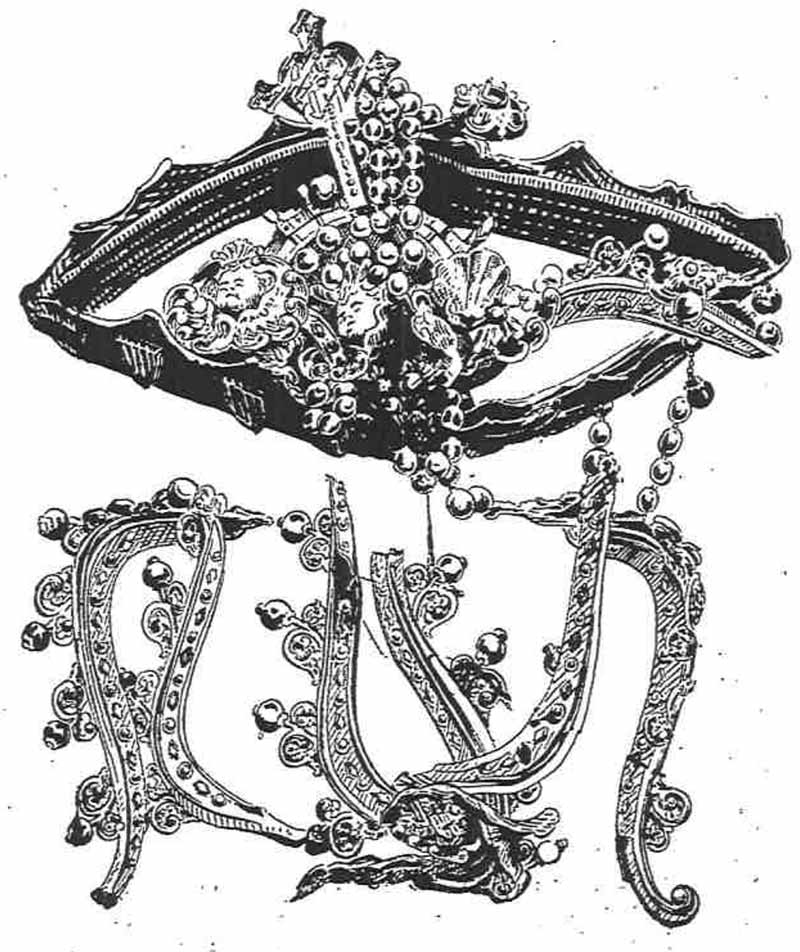

Father Carrier picked up two other items of particular importance on this trip: two crowns, each remarkable in their own way. One was a stunning crown gifted by the empress Eugenie, Napoleon III’s wife, worn on the occasion of their wedding. According to the Notre Dame Scholastic, Eugenie’s crown was “a crown of solid gold, studded with precious stones and inlaid with pearls.”

The other crown was a magnificent work of art, designed by Father Carrier and commissioned by the University with the help of 30 benefactors: a crown 20 inches in diameter at the base, two-and-a-half feet in the middle, and two-and-a-half feet tall.

According to Scholastic, “not a particle of inferior metal” was used in its creation. It was made out of 23 pounds of pure silver and nearly two pounds of gold. Hundreds of precious stones lined the arches, monde and cross at its top. Around the band, the crown featured images of the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary, stamped with the names and cities of residence of the benefactors who donated to make the piece possible. In total, the piece weighed 52 pounds.

The crown was fashioned by “one of the best and most promising young silversmiths of France,” according to Scholastic. The purchase price was $3,500 ($101,650 today), though Scholastic notes that the artistic value of the crown was likely much higher. It took five workers three months to build.

It was meant to occupy space at the literal top of the University. The crown was designed to sit atop a statue of the Virgin Mary that adorned the Dome above the University’s brand-new Main Building. Given its beauty and planned place of prominence, the crown was something of a singular campus icon, a source of pride in the University and in the faith. It was a visual signifier that Notre Dame was well on its way to actualizing the lofty ambitions Father Sorin articulated at its founding.

Father Carrier returned from France in time for the University’s consecration during the Feast of Corpus Christi on May 31, 1866. A large celebration took place that day, with more than 5,000 people from all over the country coming to campus. The New York Herald issued glowing coverage of the event, declaring, "the ceremony will eclipse everything of the kind which has ever taken place in the United States." The statue of the Virgin was dedicated that day as well, though the Rosary Crown was not installed then. Instead, the crown was placed on display inside, under the Dome, awaiting one more voyage across the Atlantic. As it was, thousands filed past to behold its beauty.

In August, Father Sorin took the crown to Rome. He planned to have Pope Pius IX bless it during an audience with the Holy Father, though that was not the main purpose of the meeting. Father Sorin sought the pope’s approval on another matter, and perhaps in a move meant to garner favor, he purchased a life-sized statue of the Virgin Mary sculpted by the pope’s nephew. Father Sorin returned to campus the next month, having secured the blessing, the approval and the statue.

Here, an important decision was made. University officials thought better of placing the Rosary Crown atop the statue on the Dome, thereby exposing it to the elements. They decided to place the crown in the Sacred Heart Church instead, suspending it over a similarly sized statue of the Blessed Virgin inside. Empress Eugenie’s crown would be situated similarly. It was placed on the head of the statue of Mary that Father Sorin purchased in Rome, which was displayed in a separate part of the church.

It proved to be a fateful choice. In April 1879, the Main Building and several buildings around it were burned to the ground — but the Sacred Heart Church was relatively unscathed.

The crowns were apparently largely undisturbed in the church for years, even amid seeming constant renovation of the building. In the fall of 1886, the Lady Chapel was being added on the north side of the church. In this state of transition, the building was relatively insecure.

It was an opportunity a small group of criminals exploited.

“Impious Hands”

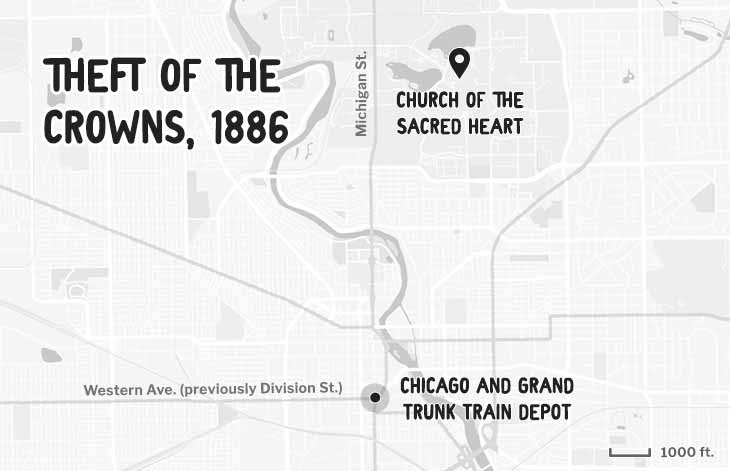

In the early morning hours of Oct. 6, thieves broke into the church by prying off a number of boards used to close up an opening at the construction site. Upon entering, they placed a ladder against the wall and scaled it to remove the Rosary Crown from its high station, and absconded with it and assorted other plunder.

According to the South Bend Tribune’s evening edition from that date, at about 4 a.m., two off-duty South Bend police officers — Officer Metz and Officer Casey — happened to be walking home after their shift when they noticed three men carrying “bundles” along the city’s Division Street (now Western Avenue). Finding their presence a bit suspicious, the officers asked what they were doing. The men responded they had just arrived on the Lake Shore train from Elkhart. But there was a problem with that explanation: There was no Lake Shore arriving at that hour. Knowing this, the cops asked the men to step into the train depot so they could search their bundles.

Here it’s best to pick up the Tribune’s account of what transpired next:

“Metz and Casey finding the fellows were unwilling to go made an attempt to force them into the passenger house when they all three dropped their bundles and made a break to run. The officers shouted ‘halt,’ but this command had no effect, and Metz shot at one who dropped in the street car track on Michigan Street and began to groan. Casey paid his attention to the other two who fled in an easterly direction. He shot at them five times, but in the darkness and fog which prevailed at the time was unable to see their forms distinctly, and they escaped, probably unhurt.

“Meantime Metz went after his man, and found, as he supposed, that he was not hurt, but only pretending.”

The officers retrieved the bundles and proceeded to question their suspect. And then they noticed something odd about his clothing. Again from the Tribune:

“The man’s vest stuck out in rather an unshapely manner and upon unbuttoning it a jeweled crown of large size dropped to the floor. It had been twisted and bent to conform somewhat to the shape of the man’s form.”

Upon hitting the floor, the Rosary Crown shattered into pieces.

Inside the bundles police found items including gold crosses, precious stones and another crown made of silver, which was completely destroyed.

The account of the robbery in the Scholastic gives a glimpse into what was taking place on campus in the meantime. It reported that “robbers broke into the magnificent Church of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart at Notre Dame and stole the two valuable crowns from the shrine of the Blessed Virgin.” The theft was discovered as the community was gathering for religious exercises at 5 a.m., at which time they noticed the long ladder the thieves had left at the scene.

Campus officials immediately called the police, and were informed that a suspect was already in custody. That suspect, incidentally, denied any involvement in the robbery. He said he came upon the other two men as he was heading to the train station and apparently was asked to carry some of the loot.

The theft made headlines nationally. The New York Times, Washington Post, and many other prominent papers picked up the story. The South Bend Tribune described for its readers the significance and station of the crown on campus, writing, “It was seen and admired by thousands of people from all parts of the world … until stolen last night by miscreants, whose impious hands destroyed its beauty forever.”

Rebirth

The loss of the Rosary Crown was a devastating blow to the University. The dollar figure mattered little; the psychological toll was crippling. Its status as the first offering made to the Blessed Virgin during the dedication in May 1866 gave it immense significance. Now, this tangible token of the Notre Dame spirit and mission appeared to have met an unceremonious end on a train station floor. Scholastic gave voice to the mood on campus over the loss of the crown:

“This large and beautiful crown was intended to be a precious and fitting souvenir of an event ever to be remembered in the annals of Notre Dame and worthy of a foremost place in the history of religion and education in America. As such even more, perhaps than its material and artistic value, this crown was treasured by all, and given its public, prominent place pendent over the beautiful marble statue of the Immaculate Conception in the church. The associations connected with it, the memories which it recalled, the bright hopes of which it was the harbinger, gave it a value to the community at Notre Dame far more precious than what its costly material and artistic workmanship could give it in the eyes of others.”

The remnants of the crown were returned to campus, where it remained an open question whether it could or should be repaired. The arches were completely detached from the band, and what stones that remained on the arches were badly damaged. The Rosary beads strung below the band were grotesquely mangled and the cross broken off.

Yet the idea of restoring it seemed worth exploring, even if it was an unlikely proposition. There’s a bit of a gap in the record, but several months after the theft Scholastic reported that a silversmith in Chicago had been secured to refurbish the crown as best he could.

If there was a desire to return the crown to its place above the Blessed Virgin statue, it likely faded when the restored crown was received back at Notre Dame. The crown was mostly back to its original shape, but was structurally irredeemably compromised. It spent time in the Sacristy in Sacred Heart Church before eventually being moved to the Main Building some years later.

Today, the crown still bears the marks of its ordeal of 135 years ago. From inside its display case on the fifth floor of Main, you can still see where the arches were bent, and where the monde is not quite securely fastened. Wires and rope hold the form in place as it rests on a custom pedestal. Opening the display case and touching the crown reveals just how fragile the piece is. The arches wiggle with the slightest brush and the whole shape of the thing seems rather precarious.

If its structure is lacking, its beauty remains. The Mysteries of the Rosary are still brilliantly stamped on the band, with the names of the benefactors clearly legible. The stones shine bright amid the natural light of the window above its display. It is easy to imagine the splendor with which the gold gleamed on that day of consecration in 1866. Not as many stream past as did then, but those who do are taken with the same sense of imagination at this larger-than-life emblem of the University’s lofty ambition and indomitable character.

The Eugenie Crown

The record of ill-fated campus tiaras does not end with the Rosary Crown.

As noted, two crowns were stolen from the church in 1886. What was the significance of the other crown retrieved from among the robbers’ loot? Was it the crown gifted by Empress Eugenie?

Turns out, it wasn’t. According to the Tribune, “the other crown was a small one made in this country and it originally cost $100.” Scholastic also does not identify the smaller crown as the gift of Eugenie, an extremely odd omission if it was the case. Moreover, the Eugenie crown was reportedly made of gold; the crown recovered from the robbery was made of silver.

Then where was Eugenie’s gift? Was it safe inside the church? Again, apparently no.

The story of what befell Eugenie’s crown may blur the line between truth and legend, with just enough evidence to make a rather surprising conclusion tantalizingly feasible. Piecing together information from a variety of sources, a picture emerges of a possible fate of Eugenie’s crown. According to this account, it’s still technically on campus … but may never be recovered.

It begins in the aftermath of the 1886 robbery. The story goes that someone at the University, likely fearful of another break-in, removed Eugenie’s crown and placed it in the laundry where criminals would not think to look for it. The problem was, this individual apparently didn’t tell anyone of their actions. The crown remained in the laundry for an undetermined amount of time before eventually turning up at Holy Cross Seminary, on the west side of St. Mary’s Lake. (The building was built in 1889 and was later called Holy Cross Hall, and was eventually demolished in the late 1980s.)

By the time of its arrival at Holy Cross, the crown apparently had faded in its beauty, wanting for upkeep and a good polish. The young seminarians used it for an altar decoration for devotions at first. Later, it was used as a stage prop for the annual Christmas play. After the turn of the century, this was apparently its main function. Plays performed in Washington Hall and even locally in South Bend featured the crown as a prop. But it always was returned to the seminary.

The crown continued to fade in appearance, likely adding to the presumption among its handlers that it was inauthentic. It was last seen intact in the late 1920s, hanging on a peg in the boiler room, before falling and finally shattering. An employee, believing the crown had finally exhausted its usefulness, swept it into the ash pile.

From here, the pile allegedly containing the crown of Eugenie, empress of France, was loaded into a dump truck. As was customary at the time, the truck backed into St. Mary’s Lake, near Old College, and dumped its contents to the bottom.

The University allegedly learned of the mistake through bizarre happenstance. An employee found some of the jewels that had been embedded in the crown and pocketed them, believing they were likely very intricately detailed pieces of polished glass. He returned to his native Netherlands for a vacation and showed the pieces to his sister. His sister then decided to have a little fun. She attempted a prank on her fiancé, taking the pieces to her beau and telling him they were jewels gifted from another suitor.

As fate would have it, the fiancé was a jeweler’s apprentice. He suspected they might be real and examined the pieces to verify his hunch. He was correct. The supposed pieces of glass were, in fact, diamonds. The employee sent word back to Notre Dame, telling them of this discovery, but by then it was too late.

It sounds a bit like a well-crafted piece of folklore, but the tale of Eugenie’s crown was accepted as fact by many at the University in the 1930s and later, including many seminarians, who would have had direct knowledge of the matter. Some attesting to the story's veracity even used the crown in plays and saw it hanging in the boiler room.

Of course, unquestioned belief doesn't account for some of the incredible circumstances of the story. For instance, why would a gift from a royal ally of the University be treated so haphazardly? Didn't anyone know it was missing? It's an unlikely prospect, to be sure, but consider this: In 1933, the South Bend News-Times reported that a six-foot bronze crucifix, another gift of Napoleon III, was discovered as workers removed a wall during yet another renovation of the Gregori frescoes in Sacred Heart Church. According to the article, “No one remembers when the cross was first ‘missed’...many priests had heard of its being given to Notre Dame and wondered where it was.” In other words, the crown would not have been the only royal gift to slip from the collective campus view.

And there’s one more piece of circumstantial evidence that may lend credibility to the ash-pile-in-the-lake theory. Records show that the University did employ a handful of immigrants from the Netherlands at the time the Eugenie crown may have met its unfortunate fate. A Brother Willibrord Polman, one of these immigrants, ran the campus bakery and brought other men from his homeland to work for jobs around the University. Thus, it’s possible that one of Polman’s countrymen was the person who visited home, custodian of the last remnants of the Eugenie crown.

At very least, there's enough to the story to capture the imagination. While the future of the Rosary Crown is more certain (efforts toward a complete restoration may be undertaken), the Eugenie crown remains fixed in campus lore for the time being, a treasure the remains of which may still rest at the bottom of St. Mary's Lake.