When coronavirus outbreaks threatened the closure of meatpacking facilities across the nation, Notre Dame historian Joshua Specht experienced a striking sense of déjà vu in the parallels to his research on meat production and consumption in the late 19th century.

National concern hardly centered on the facility workers getting sick, but instead focused on the steady supply of meat to the American table. Nothing makes a pandemic hit home, Specht says, like going to the local grocery store and discovering that it’s all out of bacon, hamburgers or steaks.

"People will feel the pandemic in a much more personal way if they experience shortages" — Joshua Specht

As a result, meat-producing facilities were designated essential and forced to stay open, regardless of the risk to workers, more than 15,000 of whom were infected with COVID-19 by late May.

A similar phenomenon occurred when Upton Sinclair wrote about Chicago slaughterhouses in “The Jungle” in 1905. Sinclair aimed to move hearts toward better treatment of immigrant workers, but his disgusting descriptions of sausage making instead inspired Congress to improve the sanitary conditions of the end product.

“This is a problem decades in the making,” Specht says. “How we produce our food has created a vulnerability to coronavirus. And it’s not easy to unwind that because all factories are built around high speeds and people crammed together.”

Specht came to Notre Dame in the fall of 2019 soon after publishing his first book, “Red Meat Republic: A Hoof-to-Table History of How Beef Changed America.” Recent events at modern meatpacking facilities have intensified interest in his research, compelling him to apply his expertise to how the same problems persist in modern times.

“All of the challenges and questions people were grappling with in the late 19th century have returned anew,” he says.

When the Senate hauled the early meatpacking barons into an investigation after “The Jungle,” their response was that they feed meat to the common man, which is very popular. They argued that “you’re going to have to accept this system, warts and all,” Specht says.

Specht coined the term “coronapolitics” to describe current events, where “the prosperity and ‘life as normal’ for the many depends on the risk of the few.” But the method is time-tested.

“Whenever anyone criticized how they produced their meat, they flipped that around and framed it as an attack on consumption,” Specht says. “So, if they have to change, then people won’t get cheap meat, and that’s exactly the playbook today.”

Specht grew up in Northern Virginia in a family that mostly worked for the federal government. He describes his father’s family as a “certain kind of generational American story” because his grandfather grew up on a farm in Oklahoma but got into the oil business. His father spent summers working on the farm, but Joshua only visited there every three or four years.

“I got interested in how we produce our food and how we connect to rural spaces as someone who feels it’s in my own story but also has that disconnect, in that I was a kid of strip malls and suburbs,” Specht says.

He went to the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, with plans to become a lawyer. But he fell in love with history and wrote an honors thesis on counterfeit money in early America. When he went to Harvard for graduate school, someone else wrote an exhaustive book on the topic, so he flipped back to his early interest in food production.

While there, he also met his future wife, Sarah Shortall, an expert in modern French history and Catholic thought, who began teaching at Notre Dame three years ago. Specht took a position teaching history in Melbourne, Australia, before an invitation as a visiting professor brought the two together at the University. He was hired to a tenure-track position during the stressful pandemic period.

"The big difference between today and the past is that some people today are increasingly concerned with the backstory of their food."

Specht says the recent media attention forced him to work forward through the 20th century history of meatpacking. Beyond what was in his book, he knew he had to be clear and careful to provide a historical perspective without getting bogged down in politics. Still, he says a recent op-ed piece titled “Cash Cows” brought mixed reactions.

“I’m not going to pretend like academic writing doesn’t have some political ideas or implications, or my perspective,” he says. “But it’s talking about issues today, very much informed by history, and about the costs of how we produce our food and how we need to rethink our food.”

It’s not surprising, he says, that most people are more concerned about food supply or food quality than they are about the fate of the people making it in faraway and invisible places. What you eat and how you cook helps define a culture.

“The big difference between today and the past is that some people today are increasingly concerned with the backstory of their food,” he says.

“Red Meat Republic” is the story of how beef went from a rare treat to an expectation at almost every meal, conquering America and giving rise to the modern industrial food complex.

The cultural significance of eating beef has a long history in Europe, where it was usually reserved for special occasions like religious feasts or holidays. In England, there was also a class element, making it a symbol of success.

“If you look at America in the late 19th century with immigrants from all over the world, you see them writing letters home,” Specht says. “They’ll say, well, life is pretty tough in America, but I get to eat meat, every meal, every day.”

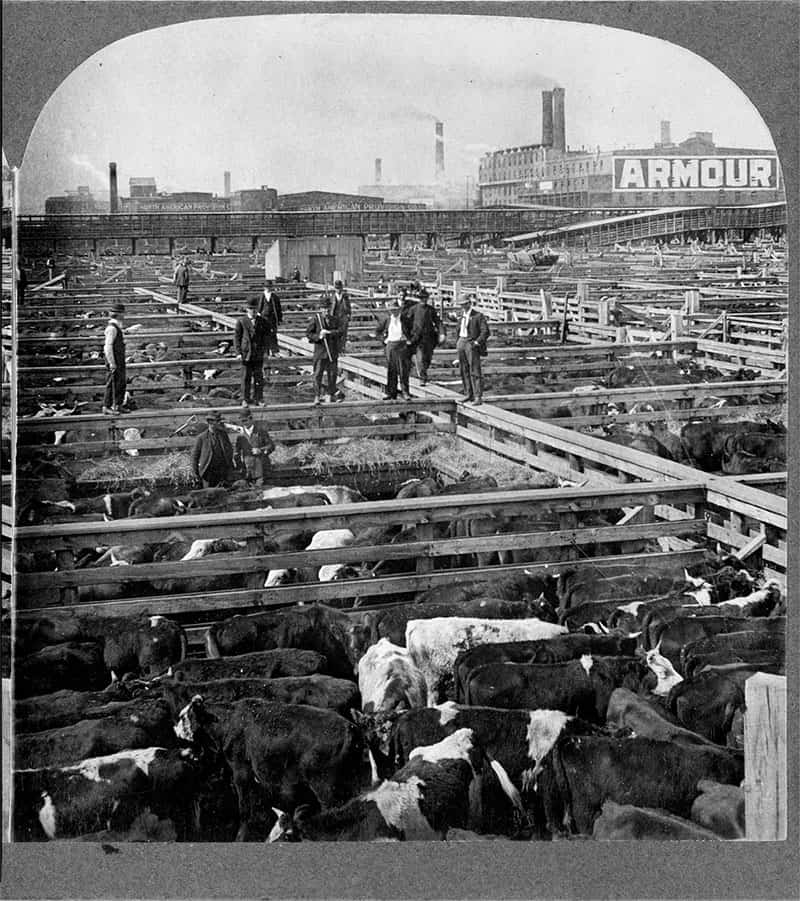

The period right after the Civil War was the high point of cowboy culture and the Western myth. The end of that century was when the Industrial Revolution took off, trains and refrigeration allowed meat to be transported long distances, and Chicago became the meatpacking capital of the world.

“You get the story of cattle ranching and the cattle trail in the West, and you get the moment when beef and the cowboy are woven into the country’s DNA,” Specht says. “What it means to be American is deeply shaped by ranching and cowboys at this particular moment.

“The connection between liberty and meat is strong. Meat became the metric for success in America, and I think that still influences the U.S. to this day.”

Specht notes that innovative methods of butchering animals changed the cost of meat. The stockyards in Chicago at the time were considered a modern wonder of the world that people went to tour. Henry Ford in his memoirs wrote that witnessing the disassembly of cows inspired his creation of the motor vehicle assembly line.

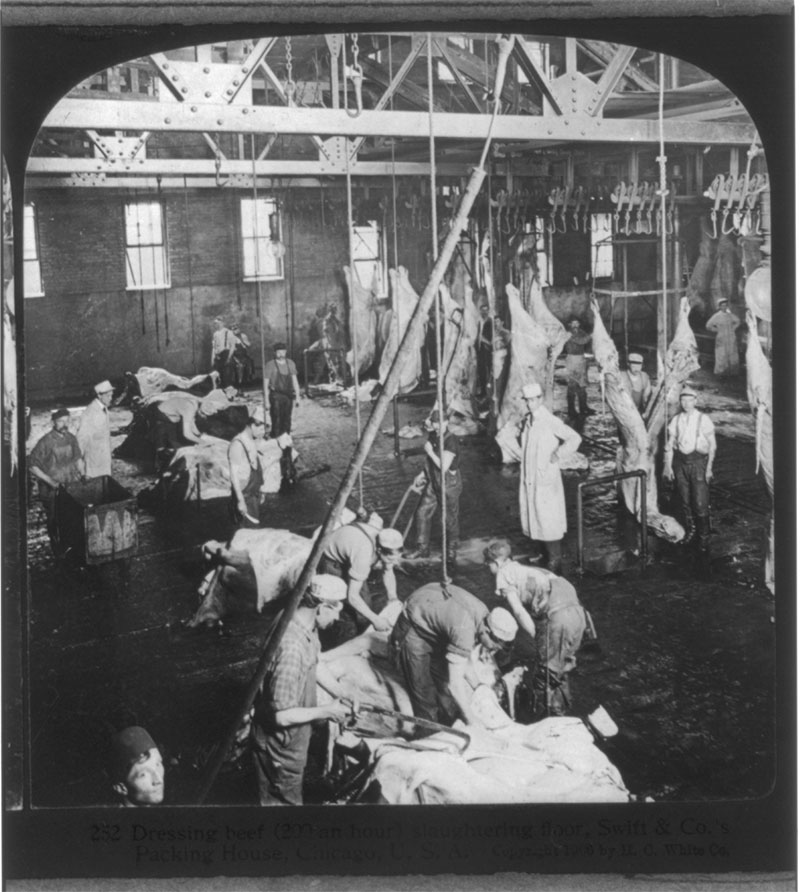

While a trained butcher could dress a couple of cows in a day, the Chicago slaughterhouses could process thousands of carcasses per day. Today’s American beef industry is even more efficient, producing more than 100 billion pounds of meat each year for worldwide consumption.

“They developed this novel system of the disassembly line, everyone working at specific tasks, working in unison,” Specht says. “And those tasks are relatively simpler so you can train people more quickly. That division of labor is a familiar story to us today, but the thing we shouldn’t forget is it also allows people to be worked harder and harder and replaced more easily.”

Modern concerns such as animal welfare and climate change related to grazing and land use, Specht says, were simply not operative during that period. The recent success of plant-based meat substitutes could disrupt the system but are unlikely to alter it permanently.

“One of reasons why the system we have wins out is that price becomes the organizing principle, and the core justification,” he says. “The animal is just an input, and once it’s reduced to an input, its exploitation is baked into the system.”

After the 1906 Meat Inspection Act that followed “The Jungle,” Specht says sanitation regulations and union organization slowly led to better working conditions at meatpacking plants. By the 1950s, the work was still difficult and dangerous, but the tradeoff was a living wage. Specht calls the changes that follow this period the second key moment in meat production, and he is interested in writing his next book about how it has affected communities nationwide.

While history still repeats itself, the silver lining is that people are now paying more attention, creating at least a potential for improvement.

After 1960, producers began to move the slaughterhouses from big cities to rural areas that are closer to where the animals live and also hostile to unions. Labor conditions began to deteriorate again. Instead of Eastern Europeans, the facilities hired African Americans, women and, later, refugees and immigrants.

“As a strategy of employment, food processors basically target vulnerable populations, people who don’t have a lot of power to fight back,” Specht says. “These are people who may not be familiar with the American legal system or as willing to push their rights because they already feel like they’re kind of tenuous. They’re often willing to accept this incredibly dangerous and relatively low-pay work.”

Coronavirus outbreaks at the plants were quite predictable, Specht says, as was the inevitability that producers would sacrifice workers to keep the public furnished with meat.

“The sacrifice, the people taking the risk of being essential workers, becomes connected to a particular population, around class, often shaped by race and gender as well, and by who works,” he says.

In his essay “Cash Cows,” the environmental and business historian put it this way:

“A version of this story is playing out across the American economy. Central to meatpacking is a brutally efficient system of labor organization paired with social forces that keep people disempowered and coming to work. Coronavirus feeds on this model which is increasingly at the core of the American economy.”

Specht says his recent research explores the tension between local American communities and national and global economic forces. He’s interested in how the opening of a meat processing plant changes a community, as does its shuttering. How we produce food will again be the central issue. While history still repeats itself, the silver lining is that people are now paying more attention, creating at least a potential for improvement.

“Coronavirus is making it impossible to avoid the concerns, at least,” Specht says. “Everyone has to look at the problems of how we produce meat. At least in terms of the human cost. I think the odds are that it’s likely the status quo will return. But I think it is a moment of real changes in the conversation.”