Editor’s note: The last names of the men at Westville Correctional Facility have been omitted to protect their privacy.

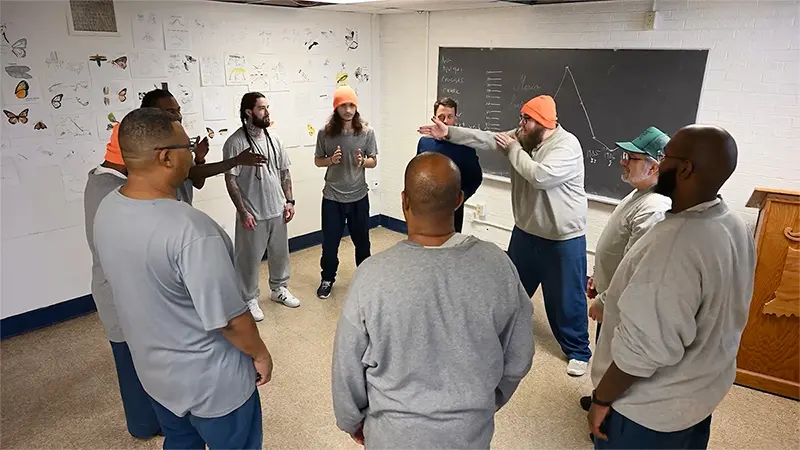

Zip! Zap! Zoom!

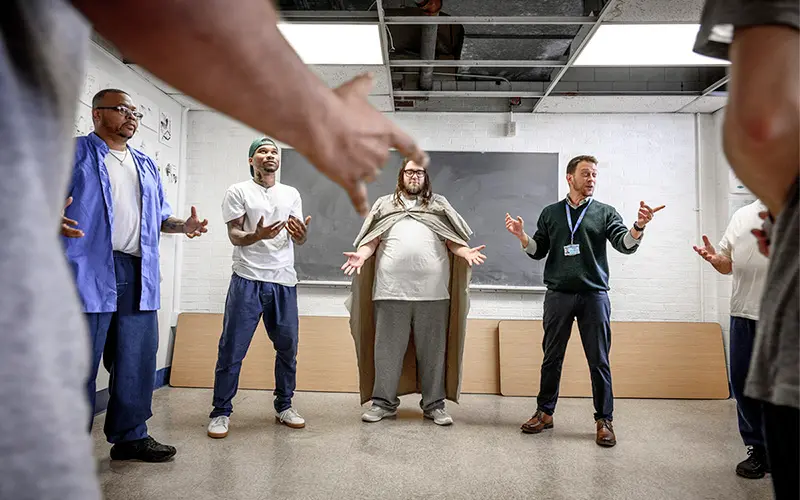

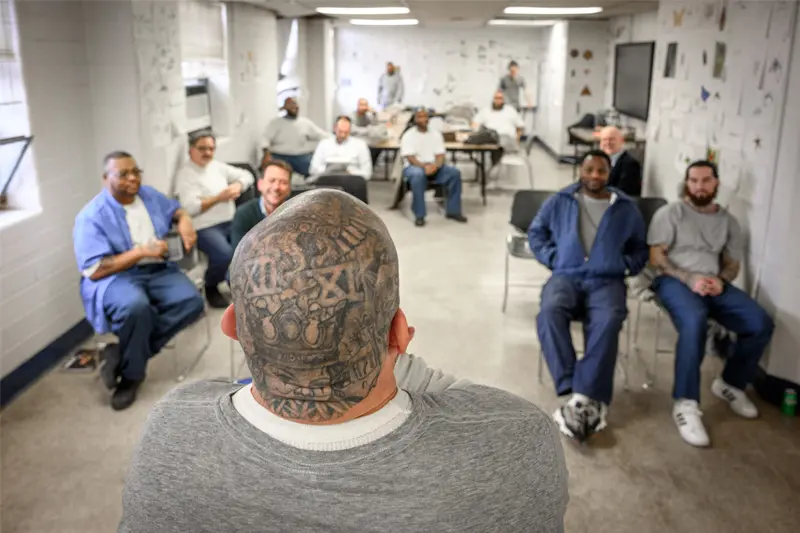

About a dozen students at Westville Correctional Facility stand in a circle and trade finger points while saying these words in a competitive game that doubles as a warm-up for an acting class.

Zip! The mood is jovial. Zap! Aaron takes the energy from Shakka and turns to send it to Antwan. Zoom! Anyone who hesitates accepts their loss and steps out of the circle without complaint.

A prison is a setting where any vulnerability can lead to physical attack. Yet the students in Scott Jackson’s Acting Shakespeare class—part of Notre Dame's collaboration with Holy Cross College at Westville—are willing to follow along with his funky warm-ups and dramatic breathing exercises.

“We’re going to be vulnerable, take the hard focus out of our eyes and be trusting,” says Jackson, the Mary Irene Ryan Family Executive Artistic Director of Shakespeare at Notre Dame. “We’re breathing out from our core, the seat of impulse and instinct.”

The students even take on the roles of female characters in the Bard’s plays and openly practice their flowery Elizabethan-era verse in the dormitory, where they live with other prisoners who may look at them askance. Mark says his bunkmate was getting worried, hearing him whispering his lines about revenge and blood—but relaxed after seeing others practicing too.

“I’m so proud of how they’ve changed the culture of the whole dormitory,” Jackson says. “I want to give them the tools to release that critical voice in the mind, that judging mind, so that they can fully invest in what success looks like in the present moment.

“If we think of the two branches of the autonomic nervous system, I’m pulling them from that activated fight-or-flight state into something where the mind is quieter in the parasympathetic state, the rest-and-digest state. Ideally what happens is that for these three hours, we cultivate a sense of presence in these guys that we transcend the space we’re in. I’m just teaching an acting class. It’s not in prison anymore.”

Based on the students’ enthusiasm for the monologues and scenes they perform, it’s working.

But why would Jackson endure the uncertain schedules, scant resources, and strict conditions that exist at Westville? On a moral level, he truly believes that these men can benefit from the class.

“They are more than the worst thing that they’ve ever done in their life, and recovering a certain sense of self starts a process of actualization,” he says. “I’ve seen participants in my program who have walked away from a monologue or a scene changed by it. They’re looking at their own life in a different way and feeling that much less alienated.”

On a larger level, it benefits all of us. The United States has substantially more people locked up behind bars than any comparable country in the world. And most of them, hundreds of thousands, will get out one day. American prisoners have a recidivism rate of about 75 percent within five years, meaning they commit more crimes and return to prison.

Shakespeare Behind Bars, a similar program with a three-decade track record, has a recidivism rate of just 6 percent of its more than 300 graduates who have returned to citizenship.

Is what’s past prologue?

One shining example is Miles Folsom. He grew up in Northwest Indiana and was first arrested at the age of 9 for stealing a toxic chemical from a water treatment plant on the edge of the woods. He liked the skull and crossbones drawing on the bottle.

That experience branded the child and hardened into a habit of stealing that culminated at age 15 in aggravated assault with a weapon during a drug robbery. A year later, he was sentenced as an adult to 36 years in a maximum-security adult prison.

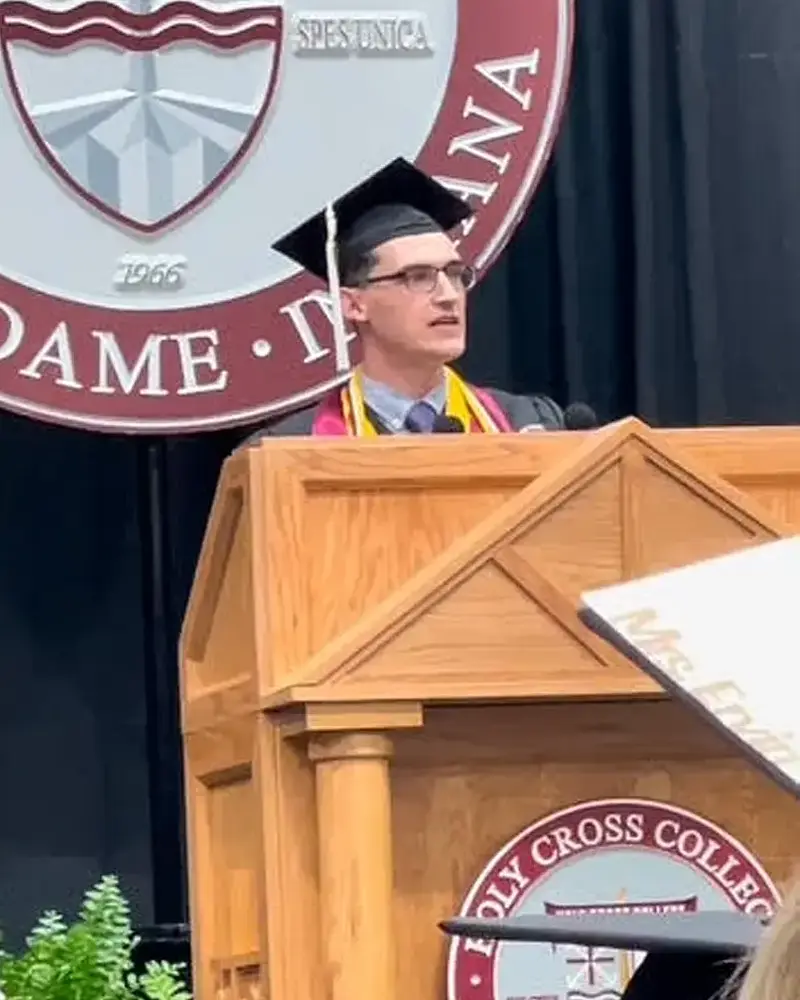

At a talk at Notre Dame in January, Folsom, now 32, says he finally found the words to change his path when he started reading voraciously in prison. He took Jackson’s class after transferring to Westville, and he got out of prison in 2020 and graduated from Holy Cross College as the 2022 valedictorian. He says the Acting Shakespeare course played a significant role in his success both while inside and after release.

“These men are in this world of incarceration, and it is a violent, aggressive world,” Folsom says. “Whatever coping looks like, it is a walling off of the world around you into a container that slowly fills with all the emotions you never let out. Every stimulus that was put into you, every jab that you never returned fills that container, and it fills it slowly, and usually not with the prettiest of things.

“The only way we ever see it drained is usually through overflow, and somebody starts yelling. But I found the performance of those words in Shakespeare to be almost a direct cathartic line to that chamber of emotions, in that I could direct them straight out and they would slowly drain.”

Folsom now runs a construction and house-flipping company in South Bend and does a lot of public speaking about his painful past. His business card reads, “My life’s mission is to build the world’s most humane prison.”

The better part of valor

Jackson arrives at the prison security gate at around 10:00 a.m. for a class in early September. Westville is about an hour west of Notre Dame’s campus.

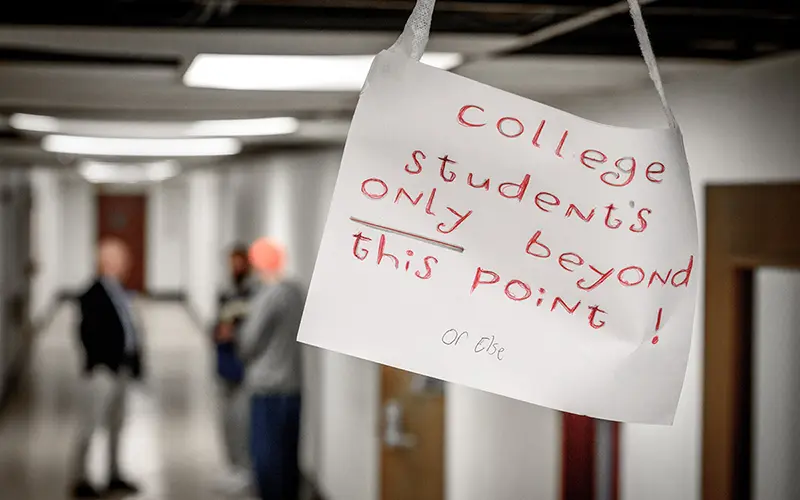

The usual security screening and frisking is friendly because he has been coming for more than a decade and knows the guards. They likely appreciate the positive influence teachers have on the prison, where the Moreau College Initiative students live in a separate dormitory and are motivated to follow the rules and keep taking classes that can earn them an associate or bachelor’s degree from Holy Cross College. MCI is a part of Notre Dame Programs for Education in Prison (NDPEP), an Institute for Social Concerns initiative that brings together a range of programs for incarcerated people in Indiana.

The long walk to the classroom building is pleasant but won’t be in December. Jackson always finds it colder behind the gates. There is no guarantee that each new class will buy into his techniques and believe there is value in acting out 400-year-old dramatic verse.

“I’ve learned so much here about how I present myself,” Jackson says. “My energy, when I walk in this space, is immediately read by these guys. They know if they can trust you or not, almost from the beginning.”

He carries nothing but a notebook and a fat volume of Shakespeare plays that he doesn’t usually need to reference. When the students suggest an act and scene of a potential monologue they might perform, he asks them to give the first few lines and then launches into the rest from memory, inevitably calling it one of his favorites.

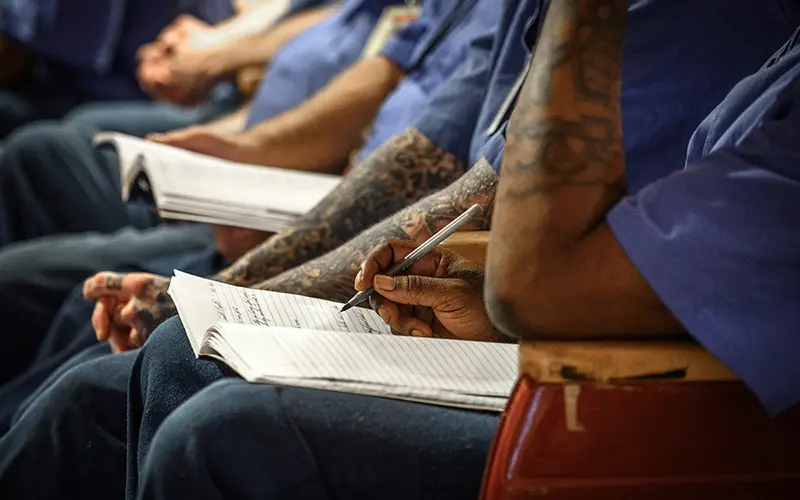

A dozen students saunter into the classroom at different times, some carrying a laundry bag with their books and notebooks, all wearing variations of the same prison-provided clothing. They vary in age from early 20s to late 50s, with every race and tattoo level represented.

Jackson quickly launches into the pranayama breathing exercises that derive from the kundalini yoga classes he also teaches at Westville. “I always go in with a Plan A, Plan B, and Plan Z to meet them where they’re at, because you don’t know what’s happened this week on the unit—if they’ve lost commissary and no one’s had sugar in a few days,” he says.

Right on cue, the “chow” call that can come at different times each day pulls the guys out for a quick lunch. The acting prep exercises will have to resume later. After break, Clarence admits that he thought it was “all voodoo” but was surprised to feel “magnetic” in his hands.

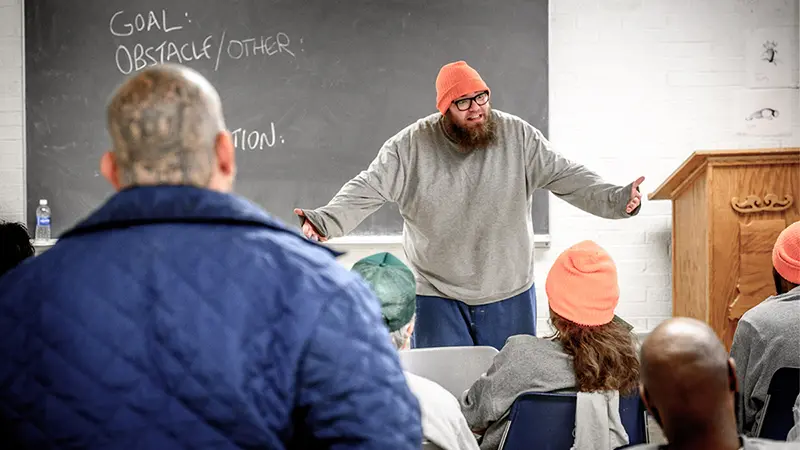

The class discusses a handout about understanding characters through a GOTE analysis: Goals, Obstacles, Tactics, Expectation. Jackson emphasizes that it’s critical to break down a scene to understand each character’s motivations—what they want at each moment.

“Goals and obstacles don’t change, but tactics are always changing with each expectation,” he says. “These acting techniques are applicable to our lives and how we interact with others.”

Jackson helps the students choose and edit their monologues for the midterm project. He emphasizes the importance of quickly memorizing their lines of verse (about 30) so they can focus on bringing the character’s words to life.

It’s now 2:00 p.m., and the same students will stay for their next class, a more traditional analysis of Shakespeare plays as literature with Steve Fallon, a retired Notre Dame humanities expert. The students are no less engaged, intensely dissecting a single question for 20 minutes: which play has the most tragic ending and why.

The play’s the thing

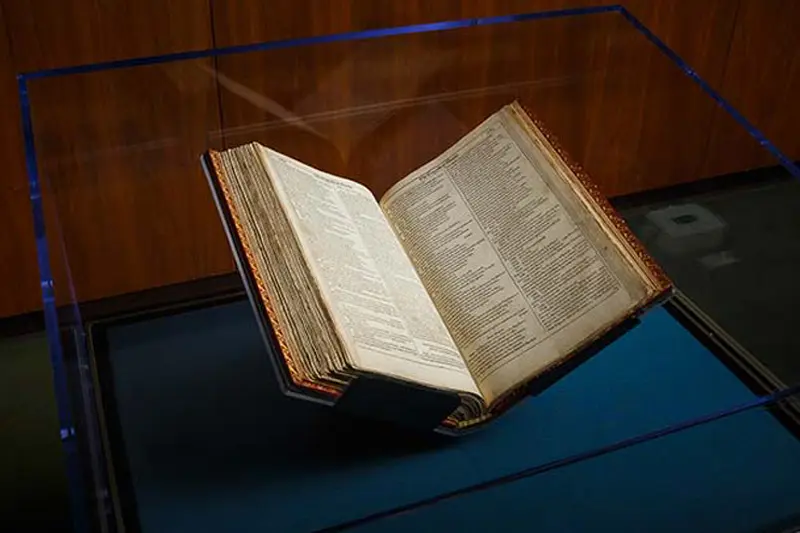

If it’s true that acting skills can help prisoners, it still begs the question of why Shakespeare.

In a webcast about the Shakespeare in Prisons Network, an international organization for practitioners that Notre Dame founded, Peter Holland contends that there is something unique about the Bard’s work—complex characters that allow people to truly encounter and consider the other.

“Many of these kids who had no expectation of finishing high school are people who have transformed their aims and ambitions through the extraordinary experience of encountering Shakespeare,” says Holland, the McMeel Family Professor in Shakespeare Studies. “They say, ‘I wasn’t going anywhere. And then I got to grips with playing a Shakespeare role and I got confidence in myself and I rethought what I can achieve.’”

In 2013, Holland and Jackson teamed with Shakespeare Behind Bars founder Curt Tofteland to launch the Shakespeare in Prisons Network and convene the first international conference of practitioners on Notre Dame’s campus. Holland says it was easy to convince the administration and funders that this fit the University’s mission and Catholic social justice tradition.

They expected about 25 participants, but they ended up having to cut off registration at 63 to preserve the budget. Four conferences later and with another scheduled in 2025, the network has grown to more than 350 individuals and organizations from 17 countries, with recent growth coming from online participation of formerly incarcerated students.

The Poverty Initiative

Notre Dame's poverty initiative emphasizes the need for better ways to improve outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Tofteland explains why the enthusiasm doesn’t surprise him: “One of the reasons that I’ve worked in prisons for almost 30 years now is because I get to bear witness to miracles of transformation, miracles of change. And that’s really what my addiction is, that miraculous thing that can happen where a light bulb goes on and all of a sudden a human being sees themself in the world in a very different way.”

Shakespeare acting courses teach prisoners to shed their old personas and embrace new roles. But can the outside public release their own dark perceptions of them and allow them to change?

Classes for people in prison may seem like an odd outreach to some, but studies have shown that earning a degree reduces recidivism dramatically, leading to a path out of poverty. Recognizing that many people exiting prisons struggle to make ends meet, the Notre Dame Poverty Initiative, a pillar of the University’s recently released strategic framework, has emphasized the need for better ways to improve outcomes for this vulnerable population.

All the world’s a stage

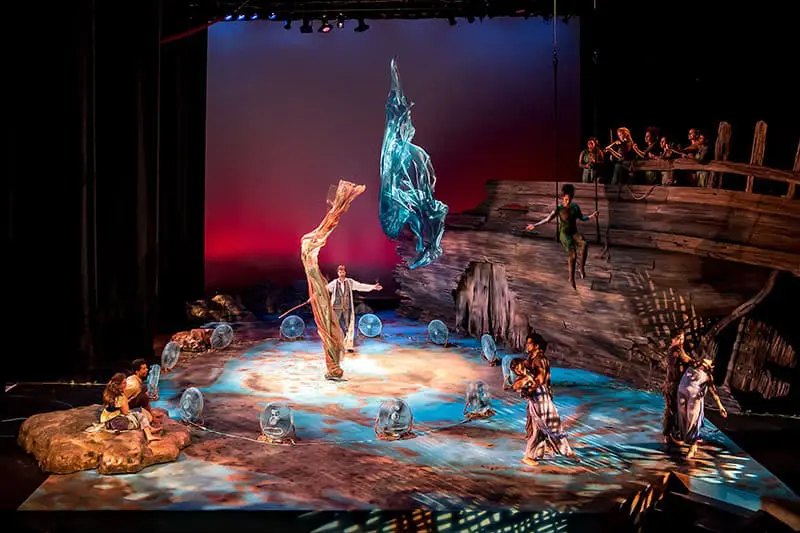

By late September, the drama is over about whether the students have bought into Jackson’s acting class. When the Actors From The London Stage visit to perform Twelfth Night, most of his students rush to the front row, many with the text in their lap to follow along.

You might not think prisoners would be entranced by watching five British actors play every role with few props in a dilapidated American Legion Hall, but many are. The students gather around Jackson at intermission to praise the drunk character and the songs, but they also ask about the significance of certain props and why there are only five actors.

“The whole show fits in a suitcase, and that’s how many people fit in a car,” Jackson answers.

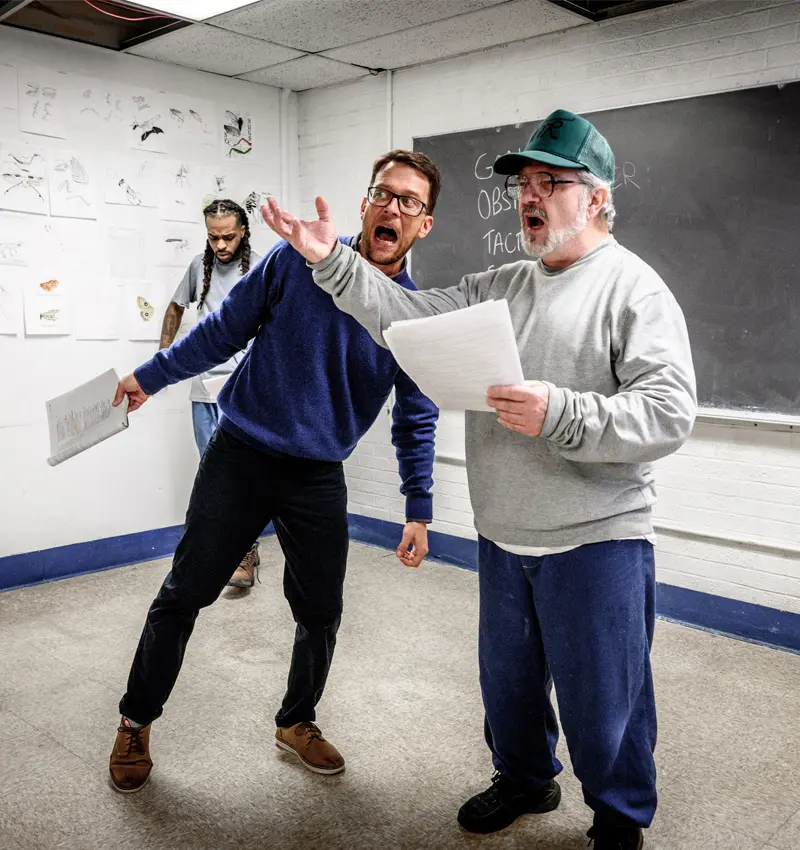

Primed to perform their own monologues and scenes, some stars emerge in the class. Danny volunteers to act out a Macbeth scene with Jackson, who challenges Danny to react when Jackson won’t respond, turning his back and scoffing.

Clarence offers encouragement: “You’re the best in the class; act like you’re going home if you overcome this.” The students help each other learn their lines, calling out the text if someone freezes, and provide constructive feedback.

“That was very intense and nerve-wracking,” Danny says. “You gotta get past the environment and the water dripping over there, and stay with the professor. It’s hard, and you have to be vulnerable, which is dangerous in prison.

“I’m taking that risk. We come to this class to build trust, build faith in humanity. The professor is giving me tools to interact with other people and make me a better person. We have to figure out how to deal with each other in here.”

When Clarence practices his scene, his earnestness overcomes his prison-fitted dentures. After being persuaded not to adopt a fake voice, Clarence brightens in response to Jackson yelling “yes, yes” as he settles in.

Davian, a young Black student, is loud and clear in voice but hesitant in movement in one scene—starkly contrasting with Mark, an older white student with a soft Southern accent. The second attempt improves by leagues as both begin to respond to the other’s energy.

“You made me pay attention there,” Davian says.

There are still some nerves about the final exam, a performance of their scenes, especially when they learn there will be a Notre Dame videographer in attendance.

Madness with method

Danny is feeling sick today, and prison sick is no joke. Joe has made a dagger out of cardboard and a cape out of a large shirt. Clarence wants to practice his scene to make sure he’s not overdoing his movements.

“Do you feel the anxiety?” Jackson asks. “You body may revolt, but trust the work you’ve done. You’ve created an ensemble.”

Breathing exercises and Zip! Zap! Zoom! get the students in the right frame of mind. Each pair performs once for their final grade and then volunteers to go again for the camera. No hesitation. Joe shares his fake dagger with Aaron. Almost no one has to request a line.

Danny digs deep enough to match Zack’s pace, speeding and peaking in volume, then slowing to a menacing whisper in rhythm with the words’ meaning. The others offer cheers and serious feedback.

“We took it to the next level, talking Shakespeare in regular life,” says Corey, whose shaved head is fully covered in tattoos. “I’m a 52-year-old ex-gang member. Who would have thought I’d be Gloucester?”

“I used to be Burger King,” Joe shoots back. “Now, I’m King Lear.”

The students are so fired up they offer to perform their midterm monologues again on camera. Other students who aren’t in the class wander in to watch, offering high-fives when they finish. Several volunteer to give their monologues again the next day at commencement. After Jackson thanks the students for their buy-in, Zack gives him a standing ovation just for teaching the class.

“People often ask me why I do it,” Jackson says later. “This is a gift that I have, a talent that I believe is beneficial for everyone to engage with. It’s a study of how life unfolds and how we respond in the moment and how we can liberate ourselves from these chains of a generational trauma or our upbringing or whatever. It just makes visible some of these psychic knots that promote a certain failure of imagination, an inability to imagine a different future.”

Miles Folsom, Jackson’s former student turned valedictorian, says the class taught him to trust that a subject he knew little about could turn into “something beautiful.” After delivering his own 40-minute talk on campus, Folsom says he had wanted to emulate how Jackson could pull up Shakespeare lines to fit a situation and deliver them with confidence.

“I didn’t have the tactics to easily overcome the anxiety and hesitation that always comes with public speaking,” Folsom says. “The class showed me that I can speak publicly, and I can do it with power. When you speak this way, the Shakespeare way, it registers different and that’s the way you want to speak.”