For Stephen Hartley, the path to becoming a better architect involves getting your hands dirty.

Hartley, an associate professor of the practice in Notre Dame’s School of Architecture, wants his students to have a deeper appreciation for the work craftspeople do to fulfill an architect’s vision—by learning the vocabulary of the trades, understanding their history, and, when possible, trying out the tools.

That was the goal behind a new class he created last fall, called Painting with Light, that explored the significance and long history of stained glass as an art form and architectural element.

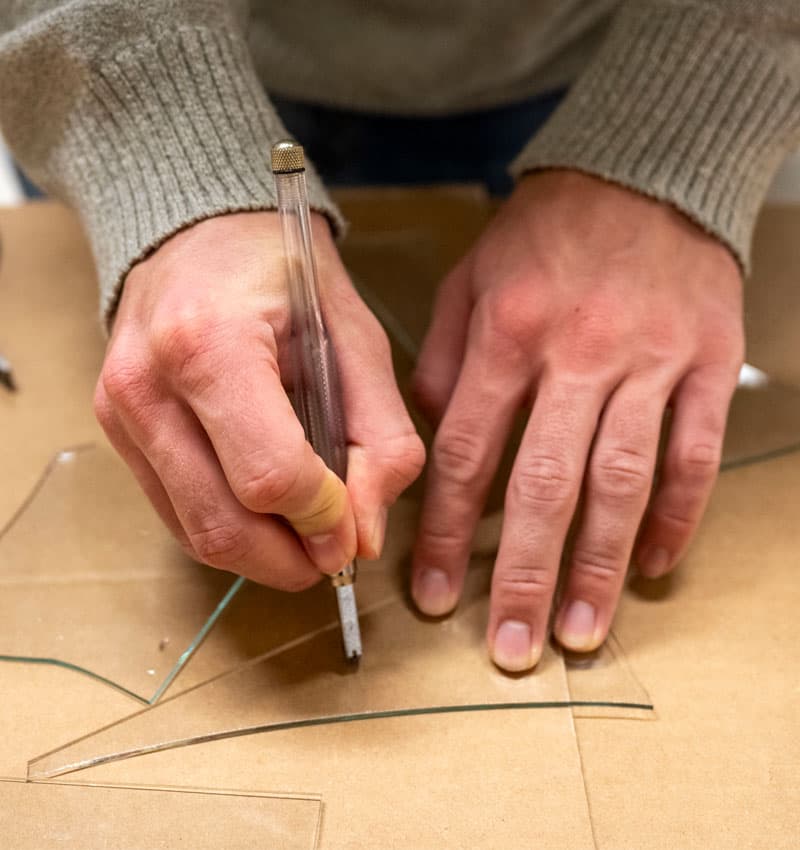

During the course, students had the chance to try their hand at various techniques including cutting and painting glass, as well as creating and presenting their own window designs. The class also worked with St. Adalbert Catholic Church on South Bend’s westside to assess and document the condition of its stained-glass windows.

“I’m not trying to train glass artists, but I am trying to help people have a greater appreciation of what it means to do this,” Hartley said. “Too often in higher education and in society, we silo ourselves, even from fields we engage with, and projects break down when we don’t understand one another’s perspectives.

“We need to return to the concept of the designer and builder working in tandem. If we all had a better understanding of everyone else’s roles in making beautiful buildings, more beautiful buildings would be built.”

Charles Z. Lawrence Collection

The idea for Painting with Light came to Hartley in 2019, when he found himself in the house of renowned stained-glass artist Charles Z. Lawrence, who had recently passed away. Hartley, who had briefly worked with Lawrence 20 years earlier, had been contacted by Lawrence’s daughter who wanted to donate some of her father’s books.

While meeting with her, Hartley learned that the artist had also kept hundreds of sketches from projects he’d worked on—including windows Lawrence did for the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, DC. Lawrence’s daughter said that she and her siblings did not have room for all the drawings they’d found, and she offered them to him.

Hartley saw the drafts not only as works of art themselves, but as an invaluable teaching tool illustrating the painstaking hours invested in designing a window. In all, he brought back more than 200 drawings and full-scale mock-ups, as well as two sample windows Lawrence created for the National Cathedral.

Painting with Light began with Hartley presenting part of that collection, and explaining each step in the process of creating a stained-glass window. After an initial sketch, the artist creates a detailed drawing showing how the design will be separated into individual panes and selecting colors for each piece. The next step is to create a “luminaire”—a mock-up of the window painted onto clear vellum and framed so that light can shine through it. The artist then creates a full-scale template for the window, with each of the hundreds of individual sections labeled. And, finally, for a project like the National Cathedral, he or she will also create sample window panels that are shipped to the site to be viewed in that light at different times of day.

Hartley estimates that an artist can work on a major project for three to five years before the windows are completed and installed.

Christina Sieben, a fifth-year architecture student with a concentration in historic preservation, said the class has given her a new perspective on stained glass.

“Just to be able to dive deep into one particular element of architecture and its history has been really amazing,” she said. “I’ve always thought, oh, stained glass is beautiful, but there’s so much more to it that I had no clue I was missing out on. I’d never thought about the intricacies of how it is put together, the pros and cons of different methods, or how it can fail or be repaired. It’s given me such a deeper appreciation of it.

“Having this understanding will help me design around it and better communicate with and advocate for the companies who do this work. It will help me as I design to really just see the bigger picture of everything I work on.”

St. Adalbert Catholic Church

One of the most meaningful aspects of the class for fifth-year architecture student Nathan Walz was the students’ work with St. Adalbert Catholic Church. Established in 1910, the parish has been a cornerstone of South Bend’s westside neighborhood—first for a primarily Polish immigrant community and now serving a predominantly Latino population.

The church, which was completed in 1926, welcomes more than 900 parishioners for Masses in English and Spanish each weekend. However, the building is in need of a new roof and extensive renovations, and last fall, the parish was awarded a $250,000 matching grant from the National Fund for Sacred Places to begin repairs.

Being able to contribute to St. Adalbert’s renovation was particularly gratifying for Walz, who has a concentration in historic preservation and hopes to focus on ecclesiastical architecture in his career.

“There’s an enormous amount of hours that go into various student projects, and a lot of those projects never leave the building,” he said. “So, it was really special to be able to create an end product that will actually contribute to this restoration.

“Buildings in the public sphere—like churches, libraries, museums, and concert halls—create a sense of community and cultural identity. It’s crucial to invest in these resources that are accessible to everyone.”

A church can also be an arrival point for an immigrant community—and St. Adalbert is doubly so, Walz continued.

“When an immigrant population comes to the U.S. and establishes themselves, a church building says, ‘We’re putting down roots. We’re here to stay,’” Walz said. “It was an important historical moment first for the Polish immigrants who founded St. Adalbert’s and then for the Hispanic community who adopted it and made it their own. And if you lose that marker, then a large part of that identity is lost as well.”

The class made site visits to St. Adalbert to photograph and document the condition of each window and then spent weeks creating a detailed report of their status and the recommended repairs for the church. Hartley hopes it will be the beginning of a longer-term partnership with the parish.

“Part of our Catholic mission is to serve the community and those in need, and St. Adalbert’s needs our help so that they can continue to serve others,” he said. “Whenever we can use our instruction to engage with our community—and allow our students to learn to communicate with clients and address real-world issues at the same time—I think that’s a success.”

Final projects

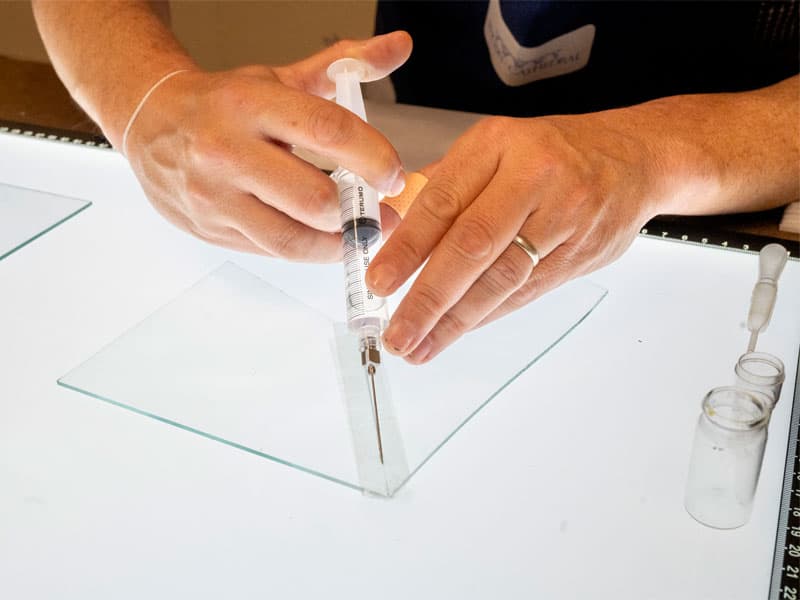

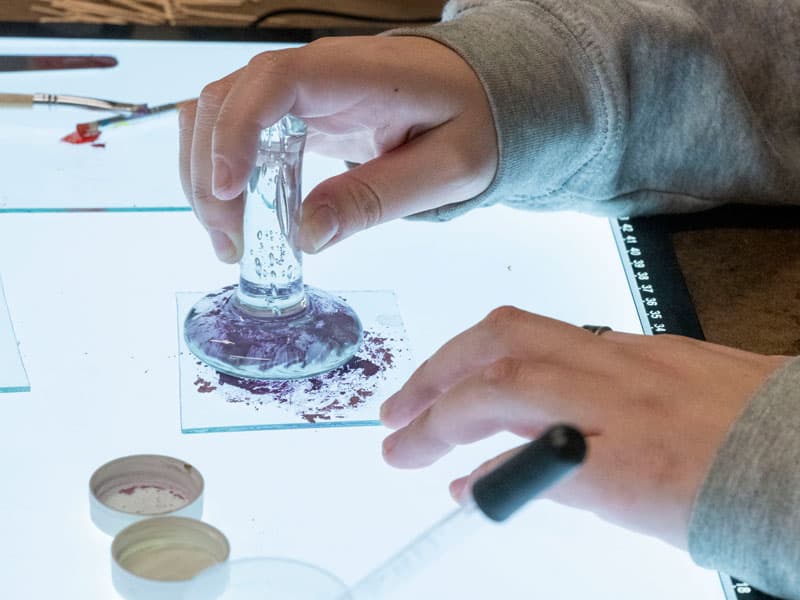

Throughout the semester, Hartley allowed the students to try out various stained-glass-making skills, from cutting glass to mixing and applying paints to a repair technique called “chemical edge bonding.”

Working in the historic preservation workshop in Walsh Family Hall and donning safety glasses to cut their own lines in sheets of glass brought everything they learned in the classroom to life, Walz said.

“I think in an experiential course like this one, you’re better able to make connections between things,” Walz said. “I came to Notre Dame’s architecture program because I was interested in buildings and how they’re put together. And the hands-on experiences we’ve had—whether that’s working with wood and stone in a historic preservation class, visiting ancient buildings in Rome, or experimenting with stained glass here—have really enhanced our learning.”

The students also worked individually and in small groups throughout the course to design their own stained-glass windows. Though they weren’t able to create permanent windows from their designs, they created and presented luminaires as their final projects.

Sieben, Walz, and senior Gabriel Goertz worked together on their final project: a three-panel luminaire depicting the evolution from the natural world to the built environment through architecture. For Goertz, a senior chemistry major, the class challenged him to think in a different way and explore an interest completely outside his discipline.

“I feel like sometimes students don’t take the time to explore their interests because they’re so career-focused. But why not get the most out of your undergraduate education?” he said. “There’s so much here that is unique to the Notre Dame experience. We’re not just a business school or a STEM school, and I’ve found a lot of opportunities I wouldn’t have anywhere else.”

Hartley plans to continue offering the class in the future and hopes to share it with more students from other disciplines—including those studying art, theology, and medieval studies—as well as architecture.

While the art form has evolved in many ways since its beginnings in the Middle Ages, stained glass as a medium has a unique power to elicit awe and wonder, he said.

“It all started with the windows being created in the cathedrals of the Middle Ages as a kind of ‘poor man’s Bible’ for those attending Mass,” Hartley said. “I can’t imagine how powerful it would have been for people in that time to step inside and see those huge expanses of stained glass, telling stories in vibrant light that they would have never seen.

“Today, stained glass still has the ability to inspire us—and to serve as a tangible expression of a spiritual connection.”