In a speech to college summer interns in 1962, President John F. Kennedy stumped for the Peace Corps international volunteer organization he created by telling a motivational story about Tom Scanlon.

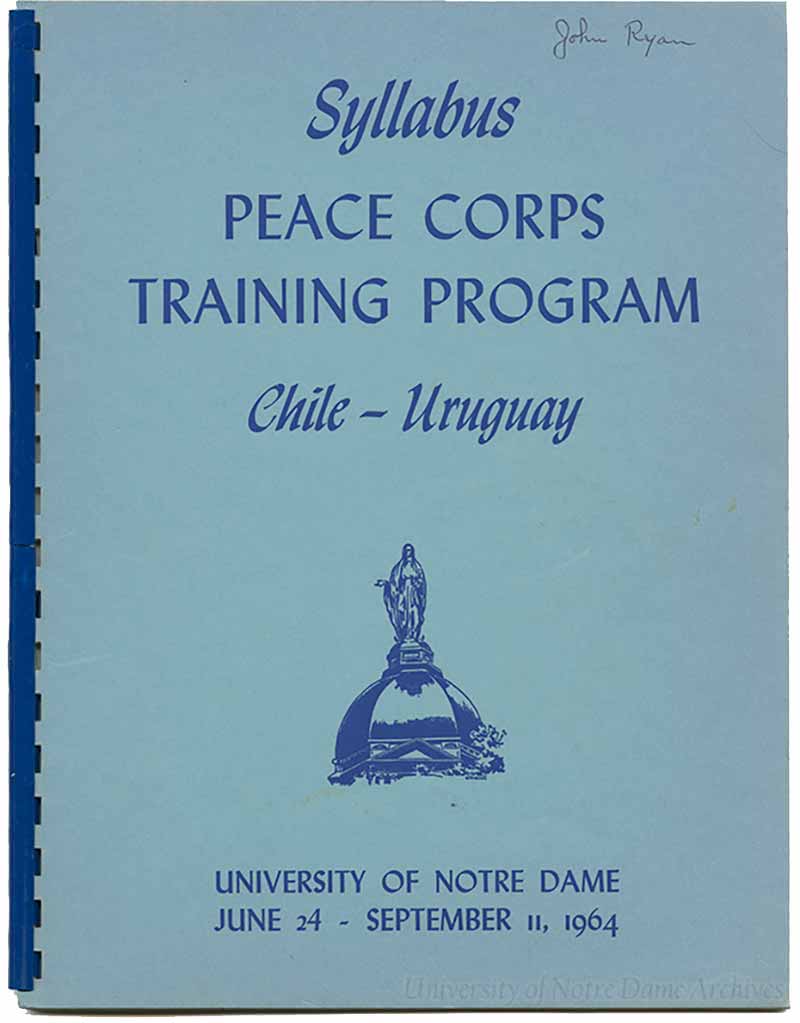

The president didn’t mention that Scanlon was a 1960 Notre Dame graduate or that the “friend” who told him the tale was Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C. Nor does the history timeline on the Peace Corps website mention the 45 young people who trained at Notre Dame and landed in Chile about a month after another cohort (Ghana) is celebrated as the first group to serve.

Ditto for a recent documentary celebrating the Peace Corps’ history, which didn’t mention the role Father Hesburgh played in helping Sargent Shriver make Kennedy’s vision possible. Even Father Hesburgh hints at some secrecy in his 1999 memoir.

“Everybody knows about the Peace Corps, but relatively few people know that Notre Dame played a pivotal role in the earliest beginning of the program,” he wrote.

Notre Dame has had a close relationship with the Peace Corps from the beginning that continues to this day. The University has sent 921 volunteers to serve since its start, including 17 who had to be evacuated in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Many returned Peace Corps volunteers who work on campus said the challenging restart of the service program this summer is a good time to remember its campus connections.

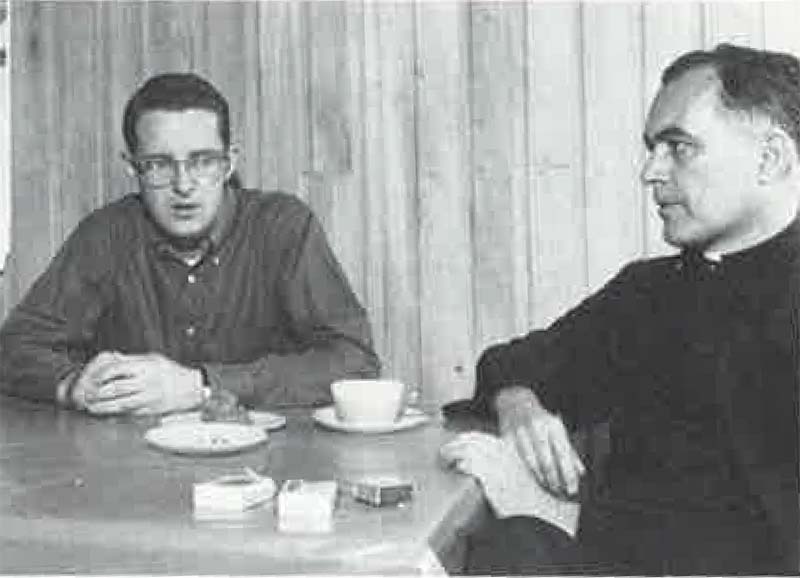

On March 1, 1961, Father Hesburgh walked out of an office near the White House that he used for his Civil Rights Commission work. He ran into his former legal secretary, Harris Wofford, and his friend Sargent Shriver, who called him over to excitedly show him a draft of the executive order creating the Peace Corps, which they expected Kennedy to sign that day.

Later that night, the pair called Father Hesburgh and asked him to provide a pilot project to begin the Peace Corps. Father Hesburgh told them to pick between Bangladesh, Uganda and Chile — three places where the Congregation of Holy Cross had worked for many years. They chose Chile, so Father Hesburgh convened a group of Latin American scholars for lunch the next day to propose ideas.

Father Hesburgh sent their plan to Shriver and didn’t hear back for weeks. Finally, Shriver admitted that some people were “gun shy” about the project becoming too Catholic, especially since Shriver and Kennedy were also Catholic in an era when that was a political liability.

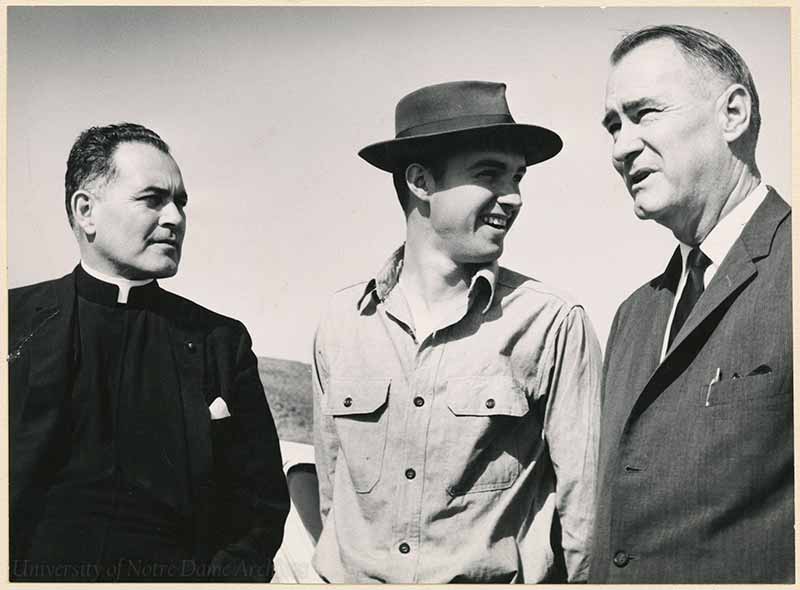

In response, Father Hesburgh brought on board the Indiana Conference of Higher Education, and he went on a reconnaissance trip to Chile with an administrator from Indiana University. They found little interest in their original plan to teach literacy through radio programming, but they formed a partnership with the Institute for Rural Education, which taught subjects like crop rotation, animal husbandry, hygiene and nutrition.

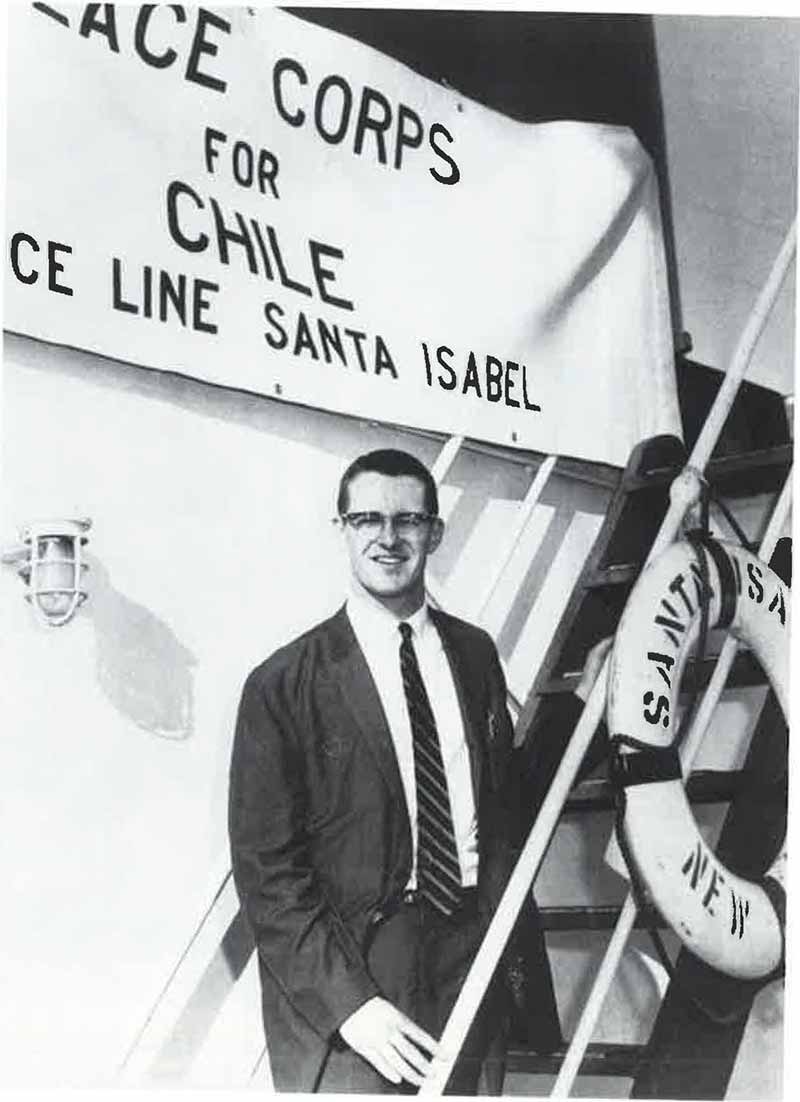

Scanlon recalled that Father Hesburgh, who personally recruited him to join the Peace Corps, welcomed all 45 volunteers by name when they arrived for training on campus — he’d memorized their names from provided pictures.

“It was a period when America’s reputation as the leader of the free world was declining,” Father Hesburgh wrote, “and many of our own young people needed a constructive outlet—for their own pent-up idealism.”

Commitment Test

Father Hesburgh starts the Scanlon story — the one that tickled JFK — this way: “He hardly knew a horse from a cow, but he organized farm cooperatives that are still in existence today.”

Scanlon had heard about three remote villages on top of a nearby mountain that the police and government avoided. He climbed up and talked to the communist leader about treating the sick and increasing profits from a special wood harvested there. The leader responded with a test of Scanlon’s determination: If you want to discuss it, come back in June when the southern hemisphere winter fills the mountains with snow.

Father Hesburgh visited every volunteer across Chile to deliver a certificate signed by Kennedy. Scanlon told his mentor he was “waiting for the snow,” a phrase that Kennedy borrowed and that Scanlon would use for the title of his memoir.

“I certainly saw our challenge as putting the best foot forward for the United States.” —Tom Scanlon

Unfazed by the ideological battle of the era, Scanlon and a nurse rode horses up the mountain in winter weather to spend a week in the villages. The nurse used penicillin to clear up a skin condition plaguing the village children, and Scanlon organized a cooperative to get better prices for the cypress wood called alerce.

The shocked leader responded: “I may be a Communist, but if you two are any example of what Americans are like, I’m all for America.”

In a pre-internet era, Scanlon learned that Kennedy had used the story when a photographer showed up a week later and told him about the speech. “Father Ted was like my PR guy,” Scanlon joked. “I certainly saw our challenge as putting the best foot forward for the United States.”

Notre Dame served as a training center for the Peace Corps for five years, until Father Hesburgh said the rules and regulations of the bureaucracy led him to conclude that the University had made its contribution.

“It was, and still is, a beautiful concept, a fitting legacy: Wage peace, not war,” Father Hesburgh wrote.

After returning, Scanlon earned a degree in international relations, worked at USAID and joined a project in Mexico before starting his own international development consulting firm in 1970.

“The Peace Corps just exposed me to a whole different world of exciting opportunity,” he said. “I’ve been running my company now for 52 years. That’s a pretty big impact.”

Last year, Scanlon did an interview with Jaclyn Biedronski, a returned Peace Corps volunteer who now works in the Pulte Institute for Global Development. The video, which includes a clip of Scanlon interviewing Father Hesburgh, was released as part of a 60th anniversary campus screening of “A Towering Task: The Story of the Peace Corps.”

Historic Pause

More than 240,000 Americans followed in the footsteps of Scanlon and the first group of 45 volunteers who trained at Notre Dame, serving in 142 countries. And while the Peace Corps has been forced to evacuate volunteers from a particular area before — due to political unrest, natural disasters or an Ebola outbreak — March 2020 broke new ground.

“It was heartbreaking,” said Andrea Tiller, who until late April served for four years as the Peace Corps recruiter for Indiana. “We’ve got evacuations down, but every single country was definitely historical. We brought 7,300-plus volunteers home from the bush in a week.”

That total includes 17 Notre Dame alumni. Despite not completing their 27-month service, all volunteers were given full benefits, which include $10,000 and programs like the Coverdell Fellowship, which provides financial assistance to pursue graduate degrees at participating colleges. About a third of the 123 universities, including Notre Dame, offer a full tuition benefit.

“This is the next 60 years for Peace Corps and this is a new world. And so a big part of the projects heading back into service are going to be related to COVID.” —Andrea Tiller

Tiller, who served in Mongolia, said restarting the Peace Corps has been much easier than in 1961, largely because the organization in the United States is well established and the program kept intact its infrastructure of employees and offices in host countries abroad.

Almost exactly two years after pulling volunteers from the field, the Peace Corps sent its first volunteers back into service in Zambia and the Dominican Republic on March 22. Another 22 countries have extended invitations to return this year, though it will take time to build back up to full strength. First priority is given to evacuated volunteers.

“This is the next 60 years for Peace Corps and this is a new world,” Tiller said. “And so a big part of the projects heading back into service are going to be related to COVID.”

Biedronski, a Pulte Institute program coordinator, certainly appreciated what the Peace Corps did for her career. She used the Coverdell Fellowship to get a master’s degree in global affairs at Notre Dame last May. Now she runs two USAID research projects, managing 11 students.

There will be some logistical challenges to re-opening volunteer sites, Biedronski said. She served from 2016 to 2018 in Mozambique, near the border with Zimbabwe, and closed down a house she and another volunteer shared because visa issues prevented the replacement of their positions.

“We got rid of the house furniture that we inherited,” Biedronski said. “They’ll need to restart leases and refurnish volunteer homes. It’s going to be like opening new sites.”

Cultural Impact

Biedronski was born in Baltimore but moved as a baby to a small coastal town in Mexico. Her family moved again to Florida when she was 13, and she majored in international studies and psychology at the University of Florida.

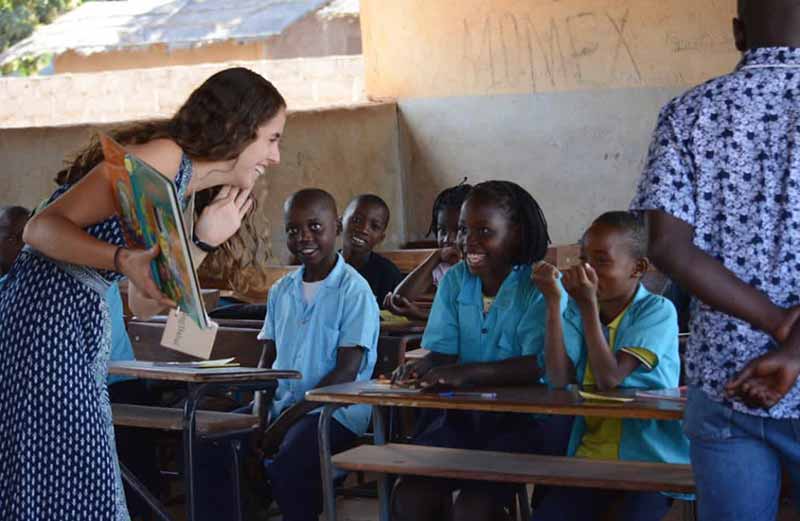

She said she joined the Peace Corps because a family friend talked about the experience when she was young. “In my 8-year-old mind, it sounded like the best thing to do,” she said. While volunteering in Ghana during college, she also met the Peace Corps veteran founder of Global Mamas, a nonprofit that helps African women improve profits from their handcrafted products.

Assigned to Mozambique, Biedronski taught English to middle schoolers in classes of 85-90. Even though she spoke the country’s common language of Portuguese, she said she quickly realized she wasn’t well-equipped to help the local people in tasks foreign to her.

“We knew we were getting a lot more than we could possibly ever give back to the community,” she said. “That creates some tension within the volunteer because you begin to have some doubts: ‘What am I doing here?’”

But development aid is only one of the three core goals of the Peace Corps. The other two are exposing Americans to the world so they can become more internationally aware, and creating goodwill in other countries through positive interactions with Americans.

“Two-thirds of the goal is that cultural exchange,” Biedronski said. “I think that’s a beautiful aspect of the Peace Corps. It provides interactions between Americans unlikely to travel to these places and communities not likely to encounter Americans.”

“I think my Peace Corps experience helps me see things with a critical eye in terms of cultural appropriateness — how we engage with individuals, and to be respectful.” —Jaclyn Biedronski

She said she was not aware of the Notre Dame connection to the Peace Corps until the Pulte Institute asked her to interview Tom Scanlon. Tiller, however, said she regularly brought up Hesburgh’s contributions as she recruited new volunteers from Notre Dame.

Biedronski said her Peace Corps experience not only brought her to Notre Dame but it opened her eyes to larger problems in developing countries. Structural issues from corruption to education to aid doing more harm than good all need policy solutions, she said. And her on-the-ground experience is invaluable in her research.

“I think my Peace Corps experience helps me see things with a critical eye in terms of cultural appropriateness — how we engage with individuals, and to be respectful,” she said. “I wouldn’t be sitting here if I hadn't done the Peace Corps.”

Ukraine Connections

The bonds that volunteers build in their host countries can be very strong. For Mathilda Nassar, her service in Ukraine from 2016 to 2018 means the current war there is painful and terrifying.

She was born in Palestine to an American mother and Palestinian father. War was a part of her childhood until she was 11 and her family went to the United States for her sister’s heart surgery. They settled in Richmond, Virginia, rather than return.

Nassar went to Roanoke College and studied international relations with a concentration in peace studies. Before coming to Notre Dame, she worked in advocacy for Palestine, especially since her family has been fighting a legal battle for 30 years to keep Israel from confiscating their farm near Bethlehem, where they run a grassroots peace organization.

At the time, she wanted to learn the Russian language, and her mother served in the Peace Corps in Senegal in the 1980s. “I had always grown up with this kind of dream of world peace — maybe it was too ideal,” she said. “I was just very inspired by the stories of her service and I wanted to have that experience.”

“I think all of us Peace Corps volunteers, we form a bond with our country of service. It’s a really special time when we grow up a lot. We have really fallen in love with Ukraine. That’s why having to watch it fall apart, it’s just really devastating.” —Mathilda Nassar

Nassar was accepted to serve in Ukraine. She taught English in a secondary school in Dubno, about two hours from Lviv in the western part of the country.

“This is a little bit removed from the fighting and the war, which I’m thankful for,” she said. “But it doesn’t make it better. Just that my loved ones there are safe for now, which is something that a lot of volunteers don’t have the privilege of saying.”

Nassar said the Ukrainian culture and national identity were so strong in her experience that she doubts Russia can conquer them. The people were energetic and loved to celebrate history and holidays with traditional music and dance. She met her husband, an American serving nearby, during her service in Ukraine.

“I think all of us Peace Corps volunteers, we form a bond with our country of service,” Nassar said. “It’s a really special time when we grow up a lot. We have really fallen in love with Ukraine. That’s why having to watch it fall apart, it’s just really devastating.”

In response to the war, a group of returned volunteers have formed a crisis support group. Their projects include raising money, sending first aid kits, raising awareness and attending protests. “It’s basically a space for us to discuss everything that we’re feeling, because it feels weird to have this world here in the West go on and everything’s torn apart there.”

Nassar received a Kroc Institute fellowship to study at Notre Dame and received her master’s degree in global affairs last May. She now works for the Flatley Center for Undergraduate Scholarly Engagement as the student engagement program coordinator, helping students apply for prominent scholarships and fellowships, including Fulbright and Peace Corps. She said her Peace Corps experience is a key asset.

“I think you learn a lot of soft skills that have helped me be kind of successful in the job market, and also in going to grad school,” she said. “And then grad school prepared me for the role I’m in right now, so it’s been kind of a domino effect.”

Father Hesburgh — who championed the Peace Corps mission to “wage peace, not war” — likely wouldn’t have it any other way.