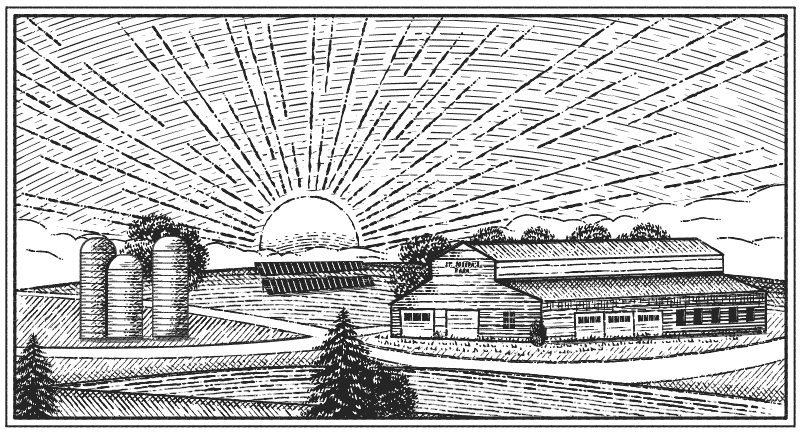

Well before sunrise every day for nearly 90 years, the Holy Cross brothers who worked on St. Joseph’s Farm seven miles northeast of Notre Dame’s campus got up at 3 a.m. to milk the cows.

Brother Angelo Trettel, C.S.C., set out for campus in the dark with 535 gallons of fresh milk for the first time in 1930 and never missed a day in his delivery truck until the dairy cows were sold in 1957. He was carrying on a tradition started by Brother Lawrence Menage, C.S.C., who came from France with Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., and helped found a Catholic college in the Indiana wilderness in 1842.

“They said Brother Lawrence drove the milk in early, then he slept the whole way home because the horses knew where they were going,” said Brother Paul Kelly, C.S.C., who lived on the farm for three years before it was sold in 2008.

The milk cows had to go after the Navy took over most of campus during World War II, since military regulations required small cartons. The brothers couldn’t compete in that market but held on for another decade before turning to beef cattle.

A delicate dance between clinging to tradition and embracing modern change has defined St. Joseph’s Farm since Father Sorin bought a 1,320-acre property in 1867. He intended to use the swampy parcel as a peat bog that would fuel campus fireplaces.

“I would think the legacy is that the farm was the life and blood of Notre Dame.” –Brother Paul Kelly, C.S.C.

For 125 years, the Holy Cross brothers — and until 1936 some hardy religious sisters — toiled on St. Joseph’s Farm to feed the students, faculty and administration of Notre Dame. Brother Kelly said they finally stopped working the farm themselves in 1995 because there weren’t enough of them left who wanted to farm.

“I would think the legacy is that the farm was the life and blood of Notre Dame,” he said. “In the early years, the farm provided the milk, eggs, apples and meat for Notre Dame. The brothers made the altar wine for the Basilica. The farm took care of them right from the beginning, and now it’s providing energy, power.”

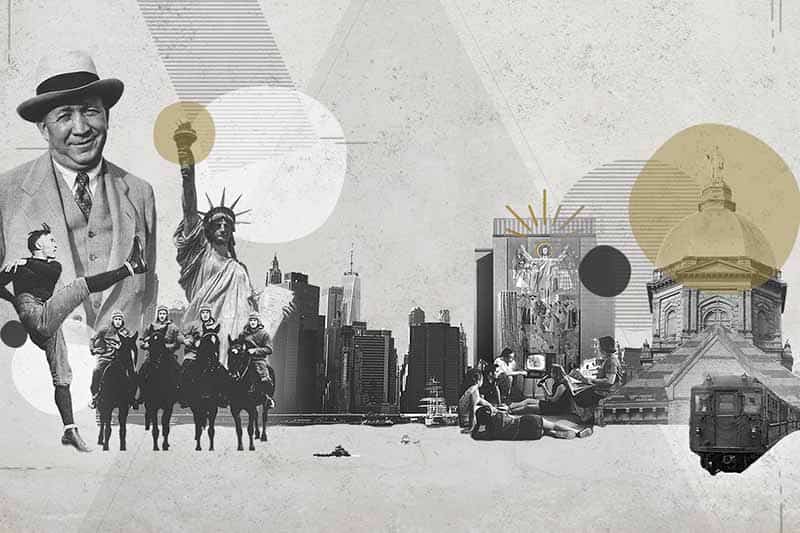

On May 6, ribbons were cut on a new partnership that carries on the tradition of the farm fueling the campus, with a modern twist. Indiana Michigan Power officially opened a $37 million solar project there that will provide clean energy credits equal to 10 percent of the University’s total demand for electricity, helping Notre Dame meet its goals around clean, renewable energy.

That transformation into the modern economy is reminiscent of another South Bend legacy. Studebaker was the only buggy maker in the country to make a successful transition to manufacturing automobiles, driving their business from the agricultural era into the industrial age. A recent renovation of a standing factory transformed the last Studebaker eyesore into a high-tech hub of the information age.

From peat fuel to fresh milk to corn and beef to solar panels, St. Joseph’s Farm has likewise adapted and endured. Current farm owners Paul and Cathy Blum appreciate its special history.

“When we bought the place, a consultant told us to knock it all down,” said Cathy, who runs an event business out of several century-old barns. “But we wanted to be good stewards to the buildings in the spirit of the brothers’ community.”

The Peat Bog

The story of St. Joseph’s Farm began with a classic Father Sorin scheme. Provincial Council records show that he bought the land in 1867 from Edmund Erwin for $10 an acre to use as cattle pasture and to “supply the college with turf.”

In a 1966 book on the Holy Cross Brothers in America, Brother Kilian Bierne, C.S.C., called the purchase a gamble because “much of it was waterlogged, and was considered little more than a marsh” that the owner was happy to unload.

Brother Lawrence Menage, C.S.C.

Born in France in 1816, Brother Lawrence accompanied Father Sorin to America in 1842 and went to Montgomery, Indiana, before joining a second group of religious coming to Notre Dame the next year. Described as having a gruff exterior, he would need that toughness as a member of the seven-person St. Joseph Gold Rush Company, which traveled 3,500 miles of rough terrain to California and back in 1850. He was among the first associated with the farm as an agent empowered by Father Sorin to buy land and the first to deliver milk to the college. The lands around Notre Dame were under his charge for 32 years until he died in 1874.

True to form, Father Sorin bought the peat bog without Congregation approval and later asked the General Council to ratify his action. The council approved and noted that his investment greatly increased a few years later when the main railroad between Chicago and New York abutted the property with a stop nearby. Father Sorin later added another 300 acres by buying an adjoining farm.

Father Sorin reported that his peat gamble was a success: “Our neighbors are astonished beyond measure that Catholics from beyond the sea have come to discover such treasure for them.”

With a grant of $400 from the University, the first barn and the Brothers’ Residence were built in 1870 with room for eight to 10 brothers and as many hired men. A Sisters’ Residence was built in 1872 for a group of Holy Cross sisters who cooked, washed, made butter, raised poultry and milked the cows.

“They endured great poverty and many hardships in the commencement of this mission,” according to the Chronicles of the Sisters of the Holy Cross at Notre Dame. “They had neither table nor chairs and only one tin cup for drinking purposes. With all these privations they were happy with the Blessed Sacrament near them.”

The main farms for Notre Dame began at its foundation right on campus, starting along the shores of the two small lakes. Around 1900, expansion moved the farm to South Quad until the need for new dorms and South Dining Hall in 1925 pushed the farms to land east of campus near Bulla Road. All farming activity eventually moved to St. Joseph’s Farm during the 1930s.

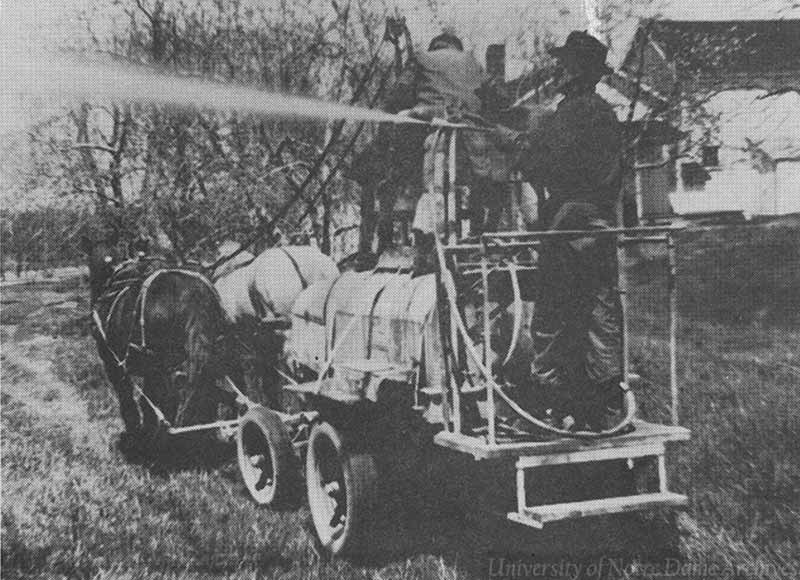

Brother Leo Donovan, C.S.C.

Although Brother Leo never lived on St. Joseph’s Farm, he was an innovative agricultural expert for Notre Dame in the early 1900s. He assumed management of Notre Dame’s 900-acre campus farm in 1900 and realized the sandy soil there was exhausted. He took agricultural courses at Iowa and Illinois universities and devised techniques of applying manure, limestone and rock phosphate to fertilize the soil, increasing yields. One 30-acre plot went from 300 bushels of potatoes to 8,200. These yields allowed greater livestock breeding, and Brother Leo’s cattle and hogs won many awards before he was named Indiana State Champion Feeder in 1937. He gave lectures around the country and helped start Notre Dame’s School of Agriculture (1917-1932).

An 1873 article in the student publication Notre Dame Scholastic describes St. Joseph’s Farm in florid terms despite the fact that poor drainage prevented cultivation on the majority of the property for another 60 years.

“Its sight impressed us with the thought of those famous monastery and convent lands of old … which we have seen often in Europe round the walls of old abbeys,” the article says. “There were the endless fields of rye and oats and wheat stretching nearly as far as the eye could see, with their beautiful green and yellow hues; there the plain of corn, and just by the rich meadows of tame hay, mowed down by four or five machines (Bless the monks! We live in an enlightened age now).”

The student visitors from the surveying class also overstated the future of peat production, noting that 800 tons a year were cut and dried and “the supply is inexhaustible for centuries to come.” Instead, it appears turf production stopped later that year when its poor quality led the University to buy woodlands to produce logs for campus fireplaces. Other Scholastic articles reveal that the three-hour buggy ride to the farm was a favorite annual visit for the grade-school Minims.

Working Farm

A record of finances in 1878 shows that besides meat and milk, the farm was supplying turnips, beets, carrots, cabbage, celery, tomatoes, squash, corn, pumpkins, beans, lettuce, fruit, onions, peas and potatoes. The same year, the brothers opened their chapel for the few neighboring Catholics, a number that would steadily grow into St. Joseph’s Farm Parish in 1936.

Holy Cross Archivist Brother Philip Smith, C.S.C., recently discovered how sisters returned to St. Joseph’s Farm. The Holy Cross sisters left in 1894 after their authority was transferred to Saint Mary’s College.

In 1903, a power struggle between the French Third Republic and the Catholic Church led to the dissolution of religious orders there, prompting thousands to leave. A group of 50 Sisters of Mary of the Presentation in Broons were trying to figure out where to go when Rev. John Zahm, C.S.C., the U.S. provincial then, offered them positions at Holy Cross colleges in America, according to an unpublished history of the sisters’ order.

Sister Fulbert Rebours, Mary of the Presentation

After the French government enacted anti-religious laws in 1903, Sister Fulbert and 50 of her colleagues from Broons were offered places at Holy Cross colleges in America by Notre Dame’s Father John Zahm. Mother Fulbert (far right) was a nurse and superior of 17 sisters who worked at St. Joseph’s Farm for more than 33 years until the last four moved to a hospital in Illinois in 1936. She cared for Rev. Gilbert Francais, C.S.C., the former superior general of the Congregation, from 1913 to 1929.

More than a dozen of these sisters ended up at St. Joseph’s Farm, where they worked until 1936. “The Sisters were put in charge of the kitchen and linen departments,” said the history, which called the farm an agreeable “solitude.” They also taught catechism to children during Mass on the farm.

In 1912, the South Bend News-Times reported that “one of the best dairy barns in northern Indiana” had been completed at St. Joseph’s Farm. Brother Onesimus Hoagland, C.S.C., who had charge of the building, said “the structure is as sanitary as it is possible to make it.” Six hired hands from Holland helped two brothers milk the 60 Holsteins in separate slots called stanchions.

That barn, the largest of its kind in the state, now hosts weddings and other events. Owner Cathy Blum said she can still feel the brothers’ presence there.

“Just walking into the event barn, you can almost hear the noises and experience the blood, sweat and hard work,” she said. “They came and lived here for 20, 30, 40 years, so this was their whole life. They gave their lives to feed the students at Notre Dame. It was their vocation and they were proud of it.”

Simple Life

Farm work defined the simple life of the brothers, but it would be a misconception to believe they felt it inferior to the spiritual work of their brother priests. Many of the brothers wanted to farm, while others accepted it as their vocation.

Brother Ken Allen, C.S.C., one of only two left who worked on St. Joseph’s Farm, said the Congregation asked his work preference when he joined, and he put “farm” in all three slots. “I didn’t want to be stuck in school,” he said by phone from Portland. “To be on a farm is a privilege because you learn so much about everything. I appreciate that the farm is not forgotten; it was a big part of my life and the community.”

Brother Richard Huber, C.S.C., worked at the farm from 1951 to 1960 and again from 1977 to 1986. Now retired at Columba Hall on campus, Brother Huber said, “I was sent there because they needed someone to milk the cows.” He later miraculously survived an accidental fall through a hay-feeding door that put him in a coma for months. “I didn’t choose it, but you lived the religious life,” he said.

In a 72-page history of St. Joseph’s Farm published in 1987, Brother Carl Tiedt, C.S.C., devotes an entire section to “The mission of Christ in manual labor.” For a farmer, “His day is spent in the dedication of his sweat and energy for Christ, and this is powerfully bound to Mission,” Brother Tiedt wrote. “All of us are involved in this mission: those who go out to work and those whose labors sustain the community itself.”

Notre Dame President Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., recalled his novitiate year working on a farm as integral to his formation. “It was where you discovered that there was more to becoming a Holy Cross priest than tending to your religious and intellectual development,” he wrote in his memoir. “Rolling Prairie was our boot camp, complete with rigorous physical training and a hard-nosed drill instructor.” He finished in good shape but knew it wasn’t for him.

Brother Paulinus Walker, C.S.C.

From Montgomery, Indiana, Brother Paulinus joined the congregation in 1918 and spent six months supervising the dining hall at Notre Dame and the next 47 years at St. Joseph’s Farm. He was in charge of the orchards and vineyards. His memoirs, included in Brother Tiedt’s book, tell amusing stories about farm hands, who were often hobos off the railroad in the Depression years. Brother Paulinus told tales of their drinking and thievery with the same fondness as those of mischievous pranks the brothers pulled on one another. He died in 1966.

St. Joseph’s Farm life was rugged even though the brothers embraced the latest technology. Various disasters struck over the years, including several floods, tubercular cows in 1922, a 1927 horse barn fire and a 1962 tornado. Indoor plumbing wasn’t installed until 1932.

Brother Paulinus Walker, C.S.C., who tended the orchards and vineyards on St. Joseph’s Farm from 1918 to 1965, said: “In the old days, modern facilities were lacking on the farm. A hand pump out of doors was the only source for water in those days when men were men and religious were hard and strong.”

Brother Kelly recalled one story of a hired hand who hauled manure at the farm. “That’s all he did for 40 years,” Brother Kelly said. “Every Sunday, he drove his car to town and got his chewing tobacco and visited friends. When he died, they cleaned out his room and found a wooden chest with gallon jars filled with all his money. He never spent much of anything.”

Peak Productivity

St. Joseph’s Farm seems to have begun its heyday in the 1930s. Factors in its emergence were the closure of the campus farms and the Depression pushing more men into religious life. Brothers also took over as superiors for the first time in 1931 and took legal possession in 1948.

The year before, the University Council denied the farm $1,700 needed to drain the marshy areas around Juday Creek. Brother Tiedt’s book says Brother Nilus Grix, C.S.C., finally “cleared the ditches with a tractor motor built on a car frame with a hand-made bucket and cable” in 1941. After further dredging with a crane and tractor in 1948, the farm expanded from one-third in cultivation to nearly all of it. Bumper crops of grain reportedly followed.

Brother Nilus Grix, C.S.C.

After two years teaching at an Indianapolis high school, Brother Nilus came to the farm in 1934 and served in different management roles until his death in 1974. Over 40 years, he was in charge of the dairy barn and heavily involved in the St. Joseph County 4-H Club for young farmers. As fair board director for nearly a decade, he helped increase the fairgrounds and added livestock buildings and a grandstand. The show arena at the county fairgrounds is named after him.

The brothers found inventive ways to make money. Two of them trapped and raised rabbits, reporting in 1940 that they sold the pelts and wrote a $185 check to the order’s foreign missions. Farm duties were highly organized into different departments: dairy, hog barns, crops, orchards, kitchen, steam plant, maintenance, painting and more.

As the local Catholic population grew, the farm parish in 1951 built a parochial school about a mile away and became a separate parish called St. Pius in 1956. The farm chapel continued operation for its religious community and families nearby.

A big blow came in 1957 after the farm lost its biggest source of income over Notre Dame’s switch to cartoned milk. The South Bend Tribune reported: “One of the nation’s oldest, largest and most prized dairy herd went out of business today.” About 1,500 buyers from 19 states attended the auction of 170 Holsteins.

“It was an emotional experience for Brother Joachim Reiniche, C.S.C., St. Joseph Farm herdsman,” the Tribune reported. “By the end of the day, he would be a man without a charge. He welcomed the crowd with the statement, ‘I’m happy to see all of you here’; then dropped the microphone as he broke into tears.”

Still, the farm adapted by switching to beef cattle. By the time of Brother Tiedt’s 1987 book, the farm had 500 steers, 27 buildings, nine grain bins, six silos and hundreds of acres of corn, wheat, soy beans and hay. Brother Angelo Trettel, a whiz mechanic who spent 51 years there, had devised an automatic feed-mixing plant for the cattle barn. There was also a thriving community life.

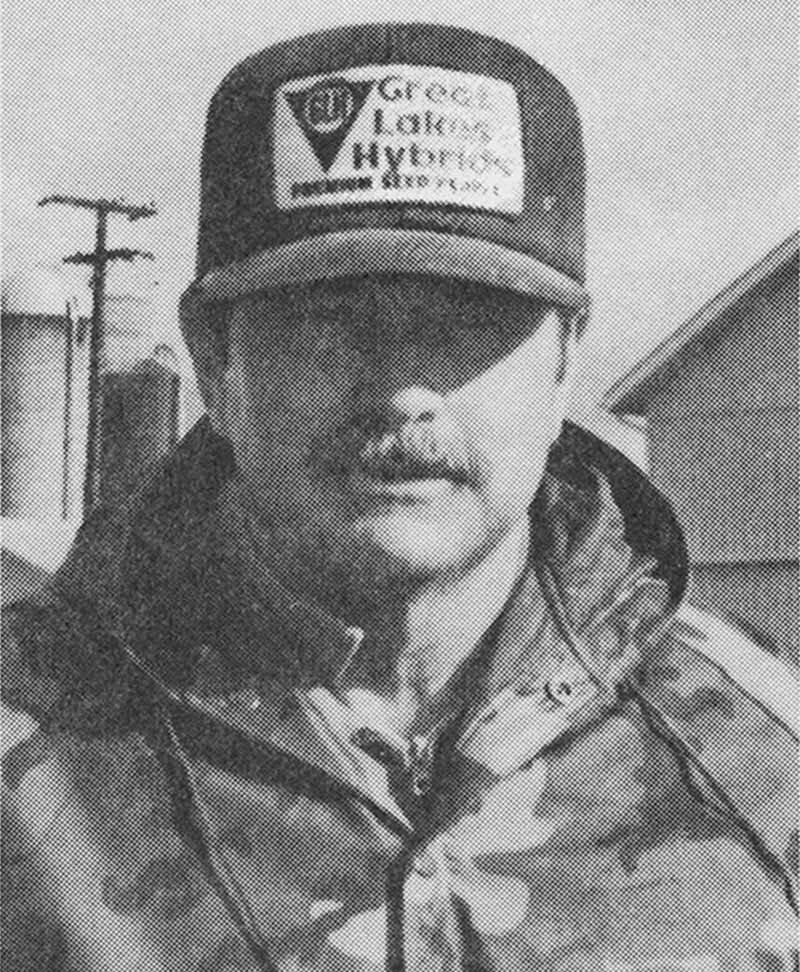

Brother Angelo Trettel, C.S.C.

Known as the “patriarch” of St. Joseph’s Farm with 51 years of continuous service, Brother Angelo came from Minnesota in 1930. An automotive mechanic by trade, he delivered milk to campus each early morning for 27 years, becoming a familiar figure on the route in his blue-striped overalls and leather cap. He kept everything running on the farm and was proud of his automated feed-mixing plant for the cattle barn. He was still active when he died on the farm in 1981.

Marquita Chamblee spent a lot of time on the farm in her youth because her father was a doctor for the brothers there and at Moreau Seminary. Interested in veterinary medicine, she worked as a farmhand there during her college summers in the late 1970s and remembers the “mystical sense of spirituality at the farm” and the noontime meals where neighbors were welcome.

“They always included a trip up to the chapel either before or right after the meal and a quick prayer,” Chamblee said. “I think I was just impressed by the level of commitment that these men had to their faith. I also saw a real deep connection to the land … and so to me the spiritual was at two levels.”

Decline and Adapt

Brother Kelly said the first time he visited the farm was in 1957 right before the dairy cows were sold. Trained as an accountant, he worked as treasurer at schools and farms until he was asked to sell many of the brothers’ properties as their numbers shrank.

“They stopped farming because we didn't have any more brothers to farm,” he said. “Brother Don Dunleavy had been there nearly 40 years, and he was worn out.”

A South Bend Tribune article from 1995 describes the auction where the brothers sold their farming equipment, starting with the morning prayer at the statue of St. Joseph.

“After silent reflection on the renewal of life, a priest will anoint those gathered with a sprinkle of holy water,” the articles says. “It is followed by the traditional blessing of the crops that this year won’t be theirs.”

“The crops will be planted in 1995 as they have been every year since 1870. But the 1,600 acres will be seeded this year by Ed Leininger, a neighboring farmer who has leased the land.”

Brother Dunleavy, who started there in 1968, continued to live on the farm for another decade until Brother Kelly was asked to care for the last director shortly before his death. According to a St. Pius Parish article, one of Ed Leininger’s granddaughters was baptized at the final parish Mass in the farm chapel in 1999.

That chapel was in the sisters’ residence, where the Blum family now lives. Paul Blum, who grew up farming in New York, saw the struggles of small farmers in the 1980s and had an idea — buy big tracts of land and lease it back to the farmers.

“All family farms died in America,” he said. “We devised a way to make them survive with more acres. They lacked economy of scale and the best technology. That improved when they got bigger. What I call the families’ farm replaced the family farm.”

Cathy Blum saw further opportunity in the old farm buildings, building up her event business, which includes one barn that local soccer clubs use in the winter. The University rented the event barn to celebrate the end of its 2017 re-enactment of the Notre Dame Trail. The same auctioneer who connected Brother Kelly with the Blums in 2008 told the family about the solar opportunity last year. The panels, hard to miss from the Toll Road, began producing electricity this year.

Paul Kempf, assistant vice president for utilities and maintenance at Notre Dame, said naming the project St. Joseph Solar Farm is an appropriate “homage to what it was long ago.”

“Food is energy, how we work as a human machine,” Kempf said. “Heating, cooling — it’s all essentially energy. There’s nothing you can do in life without energy.”

Brother Kelly said he also appreciates the solar project as a tie to the past. Before selling the farm, he removed a historic window from the Brothers’ Residence to bring to the University Archives. Scratched on a pane is a reference to the burning of the Main Building on campus:

“23 of Ap. 1879, College on Fire”