Twelve University of Notre Dame students were gathered in the offices of Philippe Villeneuve, chief architect of France’s national monuments, on the Île de la Cité in Paris — nearly in the shadow of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame.

They listened, rapt, as Villeneuve described the moment he learned that the cathedral was on fire on April 15, 2019.

“When the cathedral burned, I burned also. So, I was destroyed as the cathedral was,” he told them. “It was personal.”

Villeneuve went on to describe how he was forced to quickly put his emotions aside that day and froidement—the English word “coldly” eluded him—begin making decisions about what to do to save the iconic monument.

“She could have completely collapsed. Nobody could know what would happen after the fire,” he said. “The fire began Monday and on Tuesday I was in the cathedral to observe, to analyze, and to project the work needed to save her—not to restore, but to save her.”

This meeting came at the end of the students’ first full day in Paris, as they began a weeklong deep dive into every aspect of the cathedral’s rebuilding—talking with the architects involved, meeting with artisans and craftspeople, and traveling to one of the quarries providing stone for the restoration.

Organized by a group of undergraduates from Notre Dame’s School of Architecture, the spring break trip allowed them to take a behind-the-scenes look at one of the world’s most anticipated and closely watched restoration projects—and gain invaluable insight into the field of historic preservation.

Villeneuve went on to describe the harrowing two years of work it took to secure the structure before reconstruction work could begin and his gratitude at being able to leave behind the “spirit of fear” that encompassed the crew during that time.

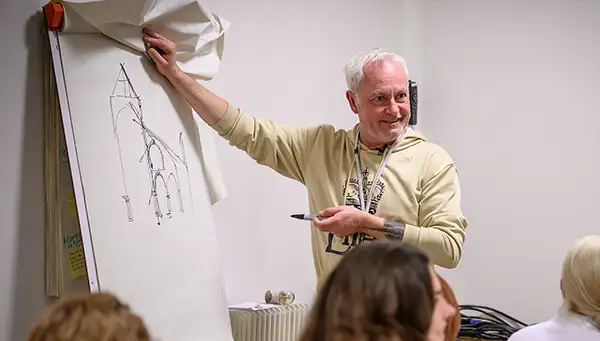

Nearly four years after the fire, he spoke animatedly to the group—including 10 students and two faculty members from the University’s School of Architecture, one graduate student from the College of Engineering and one business and French major—about the intricacies of the restoration process.

Answering their questions in a jovial mix of English and French, Villeneuve talked of how he battled to have the cathedral restored exactly as it was, the challenges of sourcing materials and labor, and the impact he hopes this project will have on future restoration work.

“This project has had such global reverberations that we’ve seen in the U.S. but that we know exist worldwide as well. What is it about Notre-Dame and about the restoration process that transcends boundaries—national boundaries, cultural boundaries, even religious boundaries?” architecture student Angelica Ketcham ’23 asked Villeneuve.

For someone so connected to the cathedral—Villeneuve had finished getting another section of a large tattoo of Notre-Dame shortly before meeting with the students—he seemed humbled and mystified by the outpouring of support it has received.

“I don’t think we knew the impact of Notre-Dame among the world before this,” he answered. “I don’t think that in France we could imagine that the fire could touch so deeply so many different people. My cathedral was destroyed by fire, and all the world came to help.”

On their first morning in Paris, the students, accompanied by architecture professors Selena Anders and Kate Chambers, visited Sainte-Chapelle, a royal gothic chapel that stands less than half a mile from Notre-Dame. Commissioned by King Louis IX, it was built in the 13th century, nearly a century before work on Notre-Dame was finished.

Together, they mark a turning point in the French gothic architecture form, Anders said.

“So, we have Notre-Dame still being completed and Sainte-Chapelle coming up,” she told the group. “This is the beginning of a kind of ‘formulization’ of Gothic architecture that gets translated to the rest of Europe. The rose window comes into Italy and other countries from France. And we’re seeing it at the beginning, the nucleus of this development here on the Île de la Cité today.”

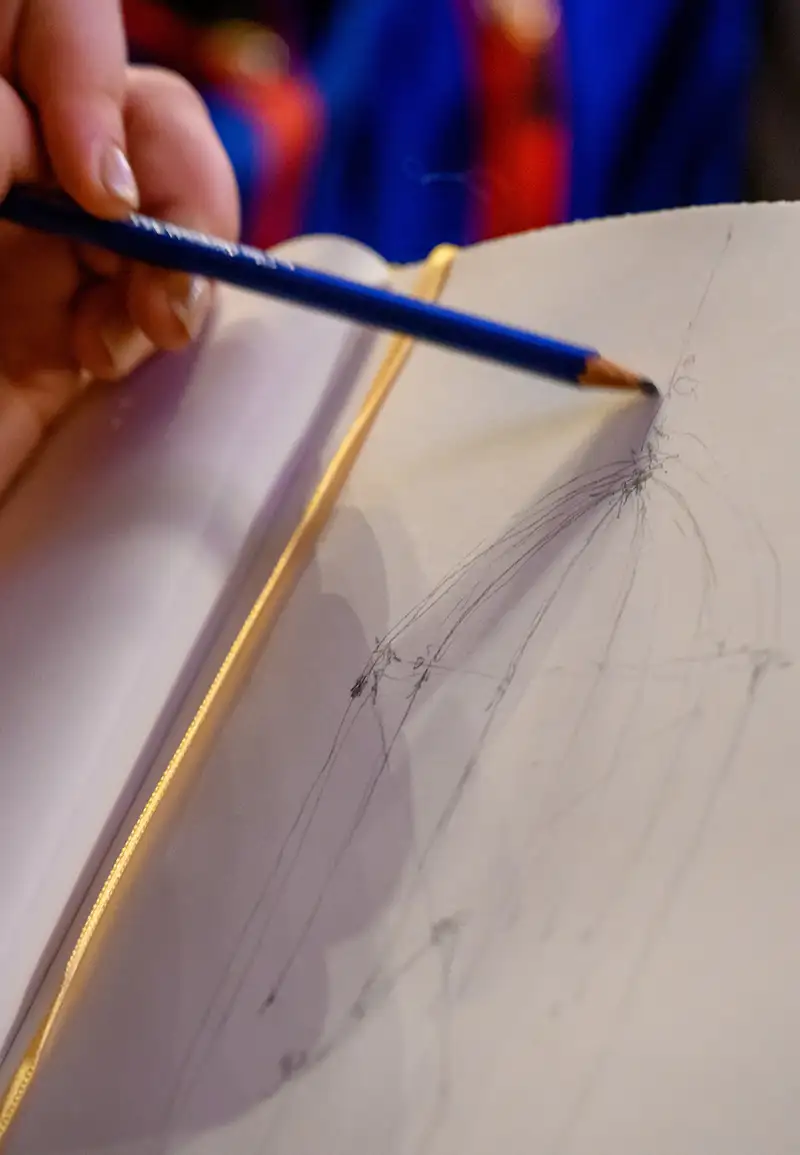

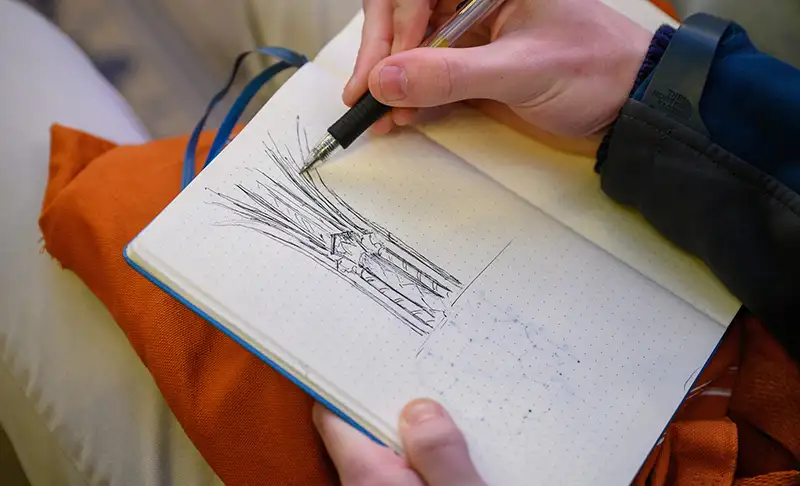

Inside the upper chapel of Sainte-Chapelle, light streamed through the 1,113 panels of the stained-glass windows, bringing the Biblical scenes to life in a kaleidoscope of color. As tourists walked through, taking occasional photos, the architecture students instead began sketching details. The Notre Dame architecture program places a unique emphasis on developing hand-drawing skills, and the students’ sketchbooks were always in easy reach.

“Being here, you’re able to absorb the city. Hearing the sounds, seeing how the people work, it helps you understand the buildings and the place in a way you couldn’t otherwise,” she said. “And drawing adds to that by helping you to look at things closer. You start to see the story in the building when you move your pencil on the page. Even if it’s just a quick sketch, it helps me file it into my memory and build this repertoire of buildings I can learn from and use later.

“Once you sketch it, you remember it forever.”

After leaving Sainte-Chapelle, the group walked the short distance to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame—getting their first glimpse of the monument shrouded in scaffolding, enclosed by a barbed wire fence, and surrounded by cranes and heavy equipment.

As an architecture student, Ketcham found beauty not only in the cathedral, but also in the temporary structures surrounding it—in what will ultimately be a fleeting moment of its history.

“It was incredible, seeing the amount of scaffolding, the number of massive vehicles needed to move pieces of the cathedral, and the enormous buttressing system of wood they had to install,” she said. “So there was the impressive rebuilding of the cathedral itself, but also the architectural beauty of the scaffolding and the things they put in place to support the building. It was very moving to see in person—and as such a temporary thing, all the more important to see on site.”

The group would have the opportunity to step inside that construction zone, but first, they spent a day visiting the Saint-Vaast Quarry, an hour north of Paris, where limestone is being sourced for the reconstruction.

Not only did stones fall from the vaulted ceiling and explode from the heat during the fire, but because the fire burned so hot—at temperatures above 1,000 degrees Celsius (above 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit)—it also changed the chemical composition and compromised the structural integrity of some of the stones that remained in place, meaning that every stone must be tested for soundness.

Donning hard hats and vests, the crew followed Nicolas Pirat as he offered them a tour and explained the process of how the stones are selected, extracted, and prepared for use as statues, as cornices, or as part of flooring, cladding, and other structural elements.

Pirat described how sample stones are sent to the architect or owner of the project to be evaluated for color and texture and, once approved, used as a reference when sourcing the materials.

From an engineering standpoint, it was fascinating, said Jack Mowat ’22, who received a bachelor’s in civil engineering and completed his master’s in structural engineering at Notre Dame in 2023.

“I loved the opportunity to visit a quarry that has sourced limestone for historic and current buildings in Paris and all over the world,” Mowat said. “I’ve taken earth science classes, geotechnical engineering classes, and a masonry class, and having an understanding of the materials that make up the foundations and the walls and the vaults of these structures is very exciting.”

The following morning, the students were ushered past the barbed wire fence at Notre-Dame to meet with Pascal Prunet, another of the architects guiding the cathedral’s restoration, and were allowed the opportunity to climb the scaffolding themselves to get a bird’s-eye view of the work.

They were close enough to see statues and carved flourishes invisible from the ground. Close enough to discuss the types of bolts used in the great wooden supports for each of the flying buttresses encircling the cathedral.

“Walking up the scaffolding was one of those moments that you realize this is really a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said architecture student Elisabeth Hanley ’23. “I felt just overwhelming gratitude that we were able to do that and for the connections and support that the University of Notre Dame afforded us to be able to go.

“It was incredible to see the cathedral at that level and be that close to it. While it is under reconstruction, you see details that people never get to see from that vantage point, looking at the different pinnacles on the flying buttresses around the back of the nave and the structural supports and seeing how each element’s a little bit different because it was built over time. But there’s a homogeneity to it, also, that was really interesting architecturally.”

The restoration process has yielded more discoveries, the students learned from Prunet, including the unearthing of two sarcophagi beneath the cathedral and the uncovering of paintings on the ceilings previously hidden by centuries of dust and candle soot.

Prunet also spoke about the challenges of rebuilding the cathedral’s vaults, which had bowed over time, even before the 2019 disaster, and the building of the new spire that required the selection and felling of massive oak trees, some of which had been planted during the reign of Louis XIV.

“Listening to Pascal, I learned a new respect for the complexity of vault construction,” Ketcham said. “Because you see this massive monolith of stone and often forget that it’s also a ton of very, very specific individual pieces. He spoke with us about the puzzle of the collapsed ceiling and the level of complexity he is having to deal with—using ancient carving techniques, choosing what quarry to source it from based on the original limestone, and the new technology needed to map where stones fell from the ceiling. That layering was incredibly impressive.”

Another challenge of the restoration prevented the students from entering the inside of the cathedral: the toxic lead dust from the 460 tons of lead used in the roof and spire that melted during the fire and coated every interior surface. At the time of the trip, even four years after the fire, the painstaking decontamination efforts were still underway.

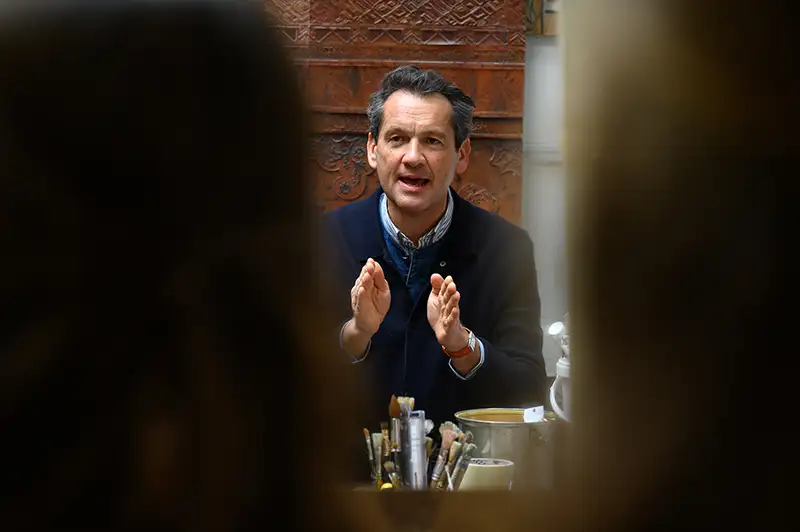

Following the Notre-Dame visit, the students continued on to the studios of Ateliers de France, a group that oversees historic restoration projects and is dedicated to preserving French craftsmanship and knowledge of historical techniques.

“On the Notre-Dame project, we have seven different companies working on stone, stone sculpture, paintings, floor mosaics in marble, etc.,” said Philippe Courtois, communication director for Ateliers. “So, Notre-Dame is very interesting for us because we have the opportunity to put all this know-how together on a single project.”

Courtois described the difficulty and importance of compiling a team of expert craftspeople when every aspect of the restoration is committed to using historically accurate techniques—like hewing wooden beams by hand with an axe—rather than relying on contemporary technologies.

“Why did the architects decide to redo the carpentry exactly the same way as the original?” he asked the group. “One reason is that they consider what we call the non-material patrimony just as important as the physical patrimony. So, you have the cathedral itself, but you also have the know-how to make it this way. And because that knowledge was not lost, they consider it very valuable to use and keep alive the techniques that we’ve kept through all these centuries.”

For Kyle Dellenbaugh ’24, who is focusing on ecclesiastical architecture, the visit to Ateliers de France was particularly inspiring.

“It’s made me see things in a whole new way—to see the kind of work they do and know that those skills are still being passed on and that we’re still capable of doing these things,” he said. “We’re still capable of building inspiring architecture that can impact the world and can make the world a better place.”

Hanley agreed, saying her experience visiting the quarry and the workshops was a good reminder of the number of people involved in the process.

“I love the fact that the knowledge and techniques are just as important as the physical patrimony and that we can transfer these skills through history,” she said.

“So many different hands go into creating beautiful buildings, and those allied arts are really important. I think we understate the value of trades in a lot of ways, and it’s good to be reminded of their value and that we couldn’t do anything without them.”

Throughout the week, the students also made visits to other historic buildings and museums throughout Paris, including Les Invalides, Beaux-Arts de Paris, and a day trip to Versailles.

“For many of these students, this is their first time coming to Paris,” Chambers, the architecture professor, said. “We wanted to help give them exposure to some of the big cultural sites while they’re here—which also relate back to the restoration at Notre-Dame, of course. We went to Versailles yesterday, and they got to see another building that has experienced many iterations over its lifetime and has undergone multiple restorations over hundreds of years—including work by Ateliers de France. And so, they are able to compare and contrast their experiences of these different monuments.”

Seeing those monuments underscored the link between historic preservation and sustainability, Fredricksen said—a lesson she’ll take with her into her practice.

“Sustainability isn’t just about protecting the environment. It’s making things that last a long time, that live beyond us,” she said. “Construction is one of the most wasteful industries, and I think as architects or future architects, we play a huge role in that. Understanding the significance of these historic buildings and how we can maintain them and make our cities last is so important.

“These lessons should be at the forefront of our education and need to be valued by students and faculty and the extended community. And I think the University of Notre Dame has been very supportive of that.”

While Chambers and Anders served as guides during the trip, both emphasized that this experience was unique because it was organized by the staff of STOA, the student magazine for the School of Architecture. The students were inspired to plan the trip after architects Villeneuve and Rémi Fromont visited the Notre Dame campus in fall 2022 and plan to dedicate the spring 2024 issue of STOA to their experiences at Notre-Dame.

“This was a student-led trip, and this is their opportunity to have their own architectural voice and their own story to tell,” Chambers said. “And it has been amazing to be able to support them in that endeavor as they move through the upper levels of architecture school and out into professional practice.”

The students made a trip to the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine museum on their last day in Paris. There, a number of artifacts from the cathedral are on display, including copper statues of the apostles—which were, miraculously, moved from Notre-Dame only a few days before the fire as part of a restoration project—alongside charred beams and fallen stones.

As part of the exhibit, alternative architectural proposals that were submitted for the cathedral restoration were also on view, including one with a modern spire made entirely of glass and another featuring a pool on the roof.

Looking at the proposals, Ketcham was grateful that Villeneuve won out and that the cathedral will be restored as it was.

“I thought it was really fantastic that one of the first questions the architects asked was, ‘Who are we to do something different? Why would we change it? It’s been here for 800 years,’” she said. “That’s the best and most humble response you could have. To take something that has been touched by so many people, especially all of the unnamed laborers who put in all the work on the stained glass, the timber and stone, and to say, no, this is my vision. It would take away from how people see Notre-Dame—as belonging to Paris, to France, to humanity as a whole.”

This trip was made possible with the support of a grant from the Nanovic Institute for European Studies at the Keough School of Global Affairs.