“Breathtaking.”

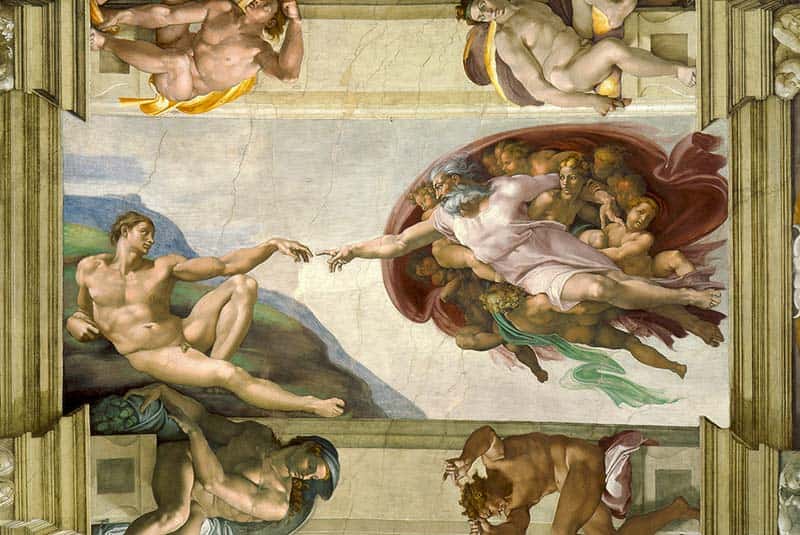

It’s a descriptor for something so awe-inspiring, so moving that an encounter doesn’t just capture our imagination and our emotions, it elicits a physical response. It’s a common reaction among the millions of people who visit the Sistine Chapel each year, where Michelangelo’s frescoes on the chapel’s ceiling depicting several Old Testament scenes (most famously, the “Creation of Adam”) are among the most recognizable and significant works of art in the world. They at once capture the imagination and contextualize faith and humanity in ways so powerful and moving that for many, an actual physiological reaction is warranted. Breath is taken away.

Several years ago, there was a sense that perhaps the Vatican Museums were becoming victims of their own success. The number of annual visitors was soaring ever higher, and as they passed through the galleries and the sacred Chapel, they brought with them dust from the outside. They also raised the temperature with their collective body heat and they did something else quite natural and necessary, but also potentially harmful: They breathed. The dirt, heat, humidity and carbon dioxide was rising to the ceiling where it settled on the paintings, threatening to degrade their appearance over a period of many years if the problem wasn’t addressed. In 2014, U.S.-based Carrier Corp. donated and installed a new ventilation system that would channel air — and the pollutants it carried — away from the artwork on the walls and ceiling. Breathtaking in the literal sense, you might say.

It was a solution with an immediate impact: The Vatican had mulled limiting the number of people allowed into the Sistine Chapel if a resolution was not found, or even creating some kind of virtual experience wherein visitors would see “Creation of Adam” in pixels, not paint. Not exactly something worth waiting in line for. Instead, the 6 million annual visitors can continue to view the works in their (climate-controlled) natural state.

“People travel for art,” says Sophia Bevacqua ’17, who is serving a five-year fellowship at the Vatican Museums. “They plan trips of a lifetime to Rome to see the Sistine Chapel and St. Peter’s Basilica because these facets of the Vatican Museums are not only masterpieces, but peak culture.”

Bevacqua works in the Vatican Museums Patron’s Office, with seven laboratories dedicated to preserving and restoring the site’s vast collections. The labs are specialized by art form: tapestries and textiles, painting and wood, ethnological materials, stone materials, metals and ceramics, mosaics, and paper. Together they form the largest art restoration complex in the world. Bevacqua is something of an intermediary in restoration projects. She works with the laboratories to determine which works of art will be restored, which methods will be used to do the work, and how much each project will cost. She then works to match upcoming restoration projects with benefaction from the museums’ pool of approximately 2,400 donors. She’s also working on an exhibition curated by Vatican Museums director Barbara Jatta of pieces that will tour major museums in the U.S.

She describes the opportunity as the result of a healthy amount of serendipity. It started as a research assistant job for art history professor Heather Hyde Minor, who was appointed academic director of the Rome Global Gateway last year. Almost immediately thereafter, she heard about the opportunity at the Vatican from a friend. The timing was indeed serendipitous, but as is often the case, good fortune was the result of hard work and experience. Bevacqua was no stranger to museum work, with stints at Notre Dame’s Snite Museum and also an internship at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, which she completed while studying at Notre Dame’s London Global Gateway.

“She is a great example of what we do (at the Rome Global Gateway),” Hyde Minor said. “I pushed her to find something that interested her, but in a practical way that I think was new and different. The fact that she’s able to have a work experience that will provide her with tremendous preparation for graduate school, and also have a research component, it’s almost ideal.”

The chance to be involved in preserving and restoring Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces, breathing new life into them for new generations, was enticing not just for its implications in the art world, but for the world generally, Bevacqua says. She calls the work of restoration “cultural maintenance.”

“I’ve learned to discuss art with a wider audience beyond the academic one,” she says. “This discussion that you have with the museum-goer, be it a written discussion or one that is developed in a curriculum, is the most important part because it facilitates the connection with the work of art that the viewer may take with them when they leave the museum.

“Restoration is a way of perpetually returning to our past. Because when you’re studying a work of art, no only in context of the theory surrounding it, but in its objecthood, you can glean a more profound understanding of how it was made and why it was made in that century.”

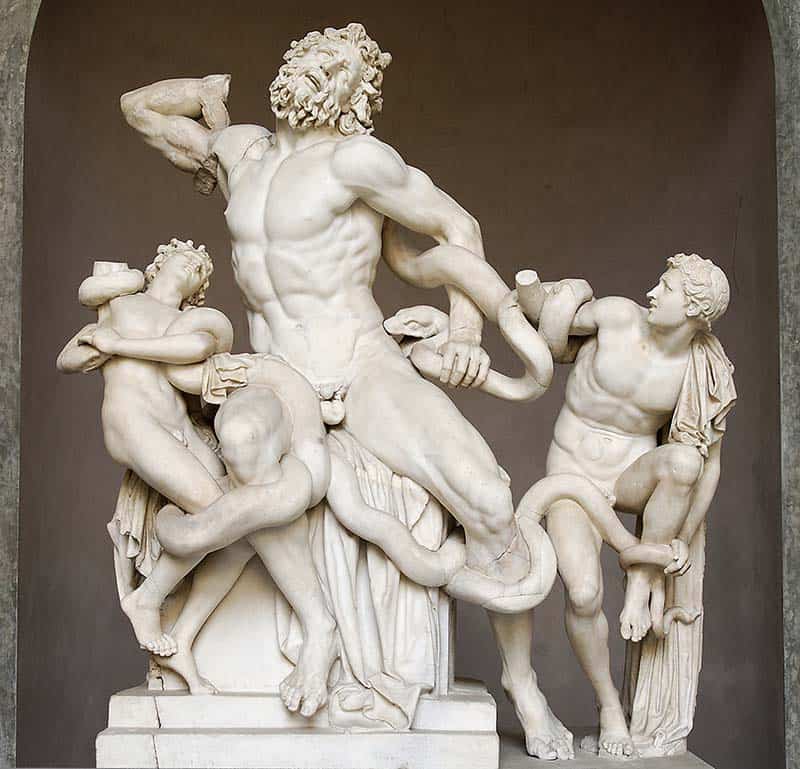

Rome, it goes without saying, is the perfect setting for considering the intersection of art, culture and civilization. Consider the statue group Laocoön and His Sons, believed to have been completed in 40-30 B.C. and unearthed in Rome in 1506. It depicts the fate suffered by Laocoön, a priest of Apollo during the Trojan War. He warned his countrymen not to accept the horse offered by the Greeks, which earned him the ire of the gods Athena and Poseidon. The gods sent sea serpents to kill the priest and his sons. The episode was said to be a deciding factor in the decision of Aeneas to flee to Italy; according to tradition, generations later his bloodline would include Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome.

The statue group has undergone a series of restorations over the centuries. When it was discovered, Laocoön’s right arm was missing. Debate ensued over exactly what form a replacement arm should take: Michelangelo believed the arm should be bent back, so as to depict Laocoön attempting to remove the serpent. Other voices prevailed, however, and an outstretched arm — believed to depict a more heroic gesture — was added. Fast-forward to 1906, when the real arm was discovered in a building yard near where the original sculpture was unearthed. It was indeed bent back, as Michelangelo suggested. The original arm soon replaced the outstretched imposter, and years later in 1980, the entire statue grouping was disassembled and restored. Did the meaning or interpretation change with the bent arm? That’s up to scholars and lay observers to discuss, but it’s the work of the restoration labs at the Vatican Museums that makes those discussions possible.

“We give our visitors the art experience as it was intended,” as Bevacqua puts it. “And also, restoration prevents a museum from becoming a tired, dusty attic full of decaying treasures from the past. Restoration injects the collection with a new vitality by continually returning to these works and ameliorating their conditions for viewer enjoyment, for the next hundred years.”

It was Pope Julius II who purchased Laocoön in 1506 immediately upon its discovery. It was the first of a collection of statues put on display at the Belvedere Courtyard at the Vatican. The collected works of art expanded in form and volume over the centuries to become the Vatican Museums. Indeed, the stated mission of the organization is to “present, preserve and share that extraordinary legacy of culture, history and beauty that the Roman Pontiffs have collected and preserved for centuries.” While Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes may be the most famous expressions of faith at the site, the multitude of other pieces that depict or interpret moments of Christian history give ample cause for the Vatican Museums to be characterized as they have: “the pope’s museums.”

The gravity of that distinction came into full view for Bevacqua in October when Pope Francis asked to meet with the staff from her office, to thank them for their efforts.

“Being raised Catholic in South Bend, Indiana, and attending Notre Dame, it’s another chapter of the Catholic experience, which in Rome takes on a very art-filled significance,” she says.

“Being able to attach the theology of Catholicism that you learn at Notre Dame to a myriad of visual, narrative illustrations within the observed Catholic faith has been a really amazing experience.”