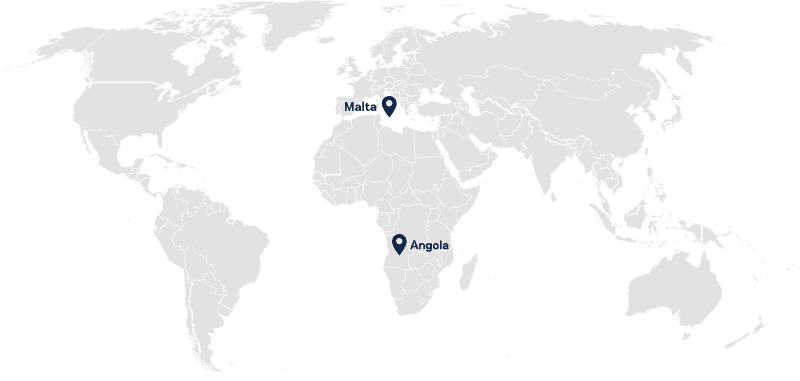

Two groups of University of Notre Dame students — one affiliated with the Washington Program and the other with the nonpartisan Student Policy Network — welcomed the announcement of sanctions against two Maltese officials and the daughter of the former Angolan president.

In December, the U.S. Department of State announced travel sanctions against Konrad Mizzi, Keith Schembri and Isabel dos Santos.

Mizzi, the former Maltese minister of energy and conservation of water, and Schembri, former chief of staff to the prime minister of Malta, are accused of awarding government contracts for the construction of a power plant and related services in exchange for kickbacks and bribes.

Daphne Caruana Galizia, a well-known Maltese journalist, blogger and anti-corruption activist, uncovered the scheme. She was later assassinated by a car bomb. Yorgen Fenech, a prominent Maltese businessman, is on trial for plotting the murder. Two of the alleged bombers are awaiting trial. A third has pleaded guilty.

dos Santos is the daughter of former Angolan Prime Minister Eduardo dos Santos, who ruled the country from 1979 to 2017. She is accused, along with her late husband, of misappropriating public funds for her own benefit as chair of a state-owned enterprise.

Students in the Washington Program’s Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act Clinic submitted to the Departments of State and Treasury a report outlining the allegations against Mizzi and Schembri, and requesting sanctions against them, in 2020. The Student Policy Network, a student-led offshoot of the Magnitsky clinic, submitted a similar report on dos Santos. Both worked with a prominent nonpartisan human rights organization, as well as George Lopez, the Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., Professor Emeritus of Peace Studies at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and a leading expert on economic sanctions, peacebuilding and related issues.

The involvement of undergraduate students in sanctions work is unusual. More commonly, such work is done by law students, pro-bono attorneys or nongovernmental organizations with some sort of background in the law.

Washington Program

The University of Notre Dame Washington Program offers students the ability to study off-campus, becoming immersed in the political and cultural life of Washington DC.Imposed by the Department of State, the sanctions against Mizzi, Schembri and dos Santos bar them and their immediate family members from entering the United States. Financial sanctions, the domain of the Department of Treasury, have not been announced, but may be forthcoming as well.

Thomas Kellenberg, an attorney and former law professor, leads the Magnitsky Clinic in his role as executive director of the Washington Program, a position he has held since the program’s founding in 1998. Kellenberg also assists the Student Policy Network with its sanctions work. He is a graduate of Notre Dame and Harvard Law School.

“We can’t show a direct causal relationship between our dossier and the (Mizzi and Schembri) sanctions,” Kellenberg said, noting the government does not typically disclose the underlying basis for sanctions, only the bare facts of the case. “But clearly, it was part of what the State Department looked at when making a decision.”

He described the impact of the sanctions as threefold. From a punitive standpoint, he said, they “preclude these people from opportunities that we have in the U.S. — to visit, to send their children to school here.” At the same time, “it is symbolically important that the U.S. recognizes that these people need to be sanctioned,” he said. “And it sends a signal to the Maltese government that they need to take corruption seriously.”

“Democracy suffers when journalists are killed.” –Thomas Kellenberg

Kellenberg, who also serves as executive director of the nonprofit International Human Rights Advocates, established the Magnitsky Clinic in the spring of 2020, just before the onset of the pandemic. He set his sights on the Galizia case early on. It was already well documented in the press. It also involved the well publicized “Panama Papers,” a leak of more than 11.5 million financial and legal documents exposing wide-spread fraud and corruption, in addition to ordinary tax avoidance, among the global elite, including Mizzi and Schembri.

“Democracy suffers when journalists are killed, so personally, I thought it was an important case,” Kellenberg said. From a student perspective, he said, it also “shines a light in a whole variety of different ways on the nexus between corruption and human rights violations.”

Said Lopez, with the Kroc Institute, “Under Tom’s leadership, this group made the most of their multi-disciplinary backgrounds in history, political science, business and economics to conduct the deep dives you need to uncover illicit money and to cross-reference the violations and atrocities they found. The work of the clinic was cited to me as outstanding by a State Department colleague working on sanctions issues in November. You don’t get this type of recognition unless your work is a difference maker.”

‘An immense amount of research’

Generally speaking, students who participate in the Magnitsky Clinic work as a team to request sanctions against an individual or entity that has engaged in “serious human rights abuses” or “significant acts of corruption” in violation of U.S. laws or policy. This involves meticulous research of public records and investigations, as well as other publicly available documents. Students rely heavily on the work of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which published the “Panama Papers.”

“It takes an immense amount of research from open-source materials,” Kellenberg said.

The Schembri/Mizzi dossier spanned 39 pages. The dos Santos one was 45 pages. Each took months to compile.

Greg Miller, a senior honors economics major from Chandler, Arizona, knows just how difficult the process can be. A former Rhodes finalist, Miller contributed to both the Mizzi/Schembri and dos Santos dossiers, first as a Magnitsky student and later with the Student Policy Network, which he cofounded with senior political science honors major Patrick Aimone, a fellow Magnitsky student and Rhodes finalist and his roommate in the Washington Program.

With respect to the Galizia case, Miller, who is primarily interested in housing policy and may go to law school, said, “I mostly worked on forming the timeline of everything that occurred to visualize how the corruption took place, particularly in relation to the timeline of the killing of (Galizia). I also created diagrams to figure out how each (shell) company related to the next and who was paying who and who was getting kickbacks.”

“It was the perfect opportunity to bring the research and writing skills I already had into this new environment and then fine tune them in a legal context.” –Greg Miller

He did the same with the dos Santos case, he said, working closely with others in the Student Policy Network, as well as human rights lawyers, to document her alleged crimes and push for sanctions against her and her husband.

From the perspective of someone interested in both public policy and the law, and simply as an introduction to the Magnitsky Act and the complicated world of international sanctions, it was a valuable experience, Miller said.

“It was the perfect opportunity to bring the research and writing skills I already had into this new environment and then fine tune them in a legal context,” he said.

He said he was sitting in his apartment eating Goldfish when news of the sanctions came down. “It was crazy,” he said. “I’m a college student eating Goldfish and there’s this international story that I’m involved with.”

In addition to sanctions work, including two pending sanctions requests, the Student Policy Network pursues other public policy research and advocacy projects as well. Recently, it published a study examining the social and economic benefits of driving cards for undocumented residents in Indiana, which is helping to inform debate around the issue in the state general assembly.

Kellenberg, for his part, praised the Student Policy Network — and Miller specifically — for its work on the dos Santos case, calling it “excellent.”

“The work they are doing is top rate,” he said. “Their dossier was as good as anything that we put together in class.”

He added, “I have the utmost respect for Greg and Patrick and the work that they are doing, and I hope that it continues.”

Miller expects that it will. He pointed to ongoing interest in the organization, as well as its mission, among students of all ages.

“We’ve created a leadership structure,” he said, “and we have high engagement. We’re getting younger individuals involved.”