Bryon Roesselet has done the math.

With more than 30 years and 70,000 hours of gilding experience, the architectural conservator and senior artist at Conrad Schmitt Studios Inc. has restored murals, sacred spaces, federal buildings, and historical interiors all over the country.

“On average, you’re up and down a 25-foot scaffold every two hours or so, which is probably on the low side,” he said. “It’s the equivalent of going up and down Mount Everest 30 times from sea level.”

It’s grueling, yet delicate work.

“With gold and gilding in particular, I think the main thing that you learn is that it’s different when you get into it from what the expectation is,” Roesselet said. “It’s not all sitting with a tiny little square of gold and a little leather pad and a little knife and picking up a leaf at a time. . . .You’re putting gold on at a completely different pace. The procedure is really good craftsmanship.”

In addition to that craftsmanship, gilding is a trade that demands patience, focus, and stamina.

The physical aspects of the job can’t be disregarded, according to Jill Eide, a historic preservationist at Conrad Schmitt who specializes in gilding. Eide has been in the trade for 25 years. She and Roesselet were among the first of the Conrad Schmitt team to start work on the 12th regilding of the Main Building’s Golden Dome.

“Some (jobs) are cakewalks and easy,” Eide said. “And some you’re dealing with elements and the physical aspect of it, which takes a toll on us.”

This is Eide’s fourth dome. She has gilded state capitol domes in New Hampshire, Maine and Colorado.

Maneuvering around scaffold, sweating through hot days, fighting wind and weather, this particular project is no cake walk.

A thunderstorm might prompt an evacuation of the site. A rainy day could slow the work. Even sunny days are unpredictable, with winds carrying bits and pieces of micron-thin gold leaf across campus.

This trade is part art, part science—part endurance sport.

The gold standard

To cover the Dome (approximately 6,500 square feet) and the 17-foot-tall, 4,000-pound statue of Mary, Roesselet, Eide and the Conrad Schmitt team will use 23.75-carat gold—which is actually better for gilding than pure 24-carat gold.

The gold leaf is sourced from Giusto Manetti Battiloro, one of the world’s leading producers of gold leaf. The company has been practicing the art of gold beating for more than 400 years. Ingots—solid blocks of gold—are reduced to thin sheets of gold leaf in what is a multistage process until each gold leaf is only 250,000ths of an inch thick.

For the Main Building project, Roesselet, Eide and the Conrad Schmitt team will use what’s called “double gold,” which equals 30 grams of gold per 1,000 leaves.

“All the wonderful artifacts from ancient Egypt that had gold leaf on them, (that) is essentially the same gold leaf that we’re using today,” Roesselet said. “And it’s produced essentially in the same way it’s produced today. You put it between layers of leather and you pound on it until it gets thinner and you keep getting it thinner and thinner and get it to the shape you want.”

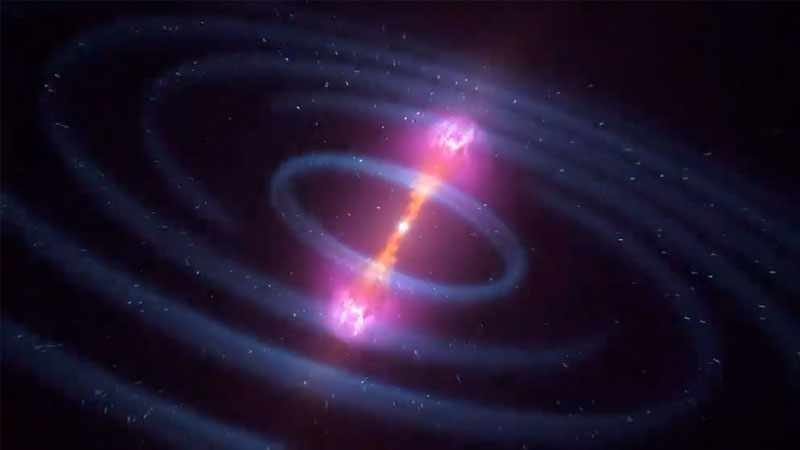

A gift from the stars

Believed to have been discovered around 3000 B.C., it’s easy to forget that gold is otherworldly—the result of a cosmic collision between neutron stars crashing into one another, setting off a chain of nuclear reactions, forming neutron-heavy metals and scattering them across the universe.

Primary deposits occur when minute quantities of gold in rocks dissolve in hydrothermal waters above magma at the core of volcanoes, according to Jeremy Fein, professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences.

As the water works its way up through Earth’s crust and cools at the surface, the gold precipitates in higher concentrations in its metallic form, typically forming with crystalline quartz in veins within the rock.

Those primary deposits provide far more gold for use volumetrically than secondary deposits—nuggets and fragments that break free from rock through erosion, washing into streams and rivers with other sediment, Fein said.

Gold’s lack of reactivity to oxygen makes it the most malleable of metals. Its electrons move close to the speed of light, contributing to its signature and mesmerizing hue.

The Egyptians gilded sarcophagi with gold leaf, used the metal for jewelry, and hammered it into thin sheets for sandals. Cleopatra wore a thin layer of pure gold as a nightly face mask—a beauty treatment that is still used today.

For centuries, powdered gold mixed with sap from lacquer trees has been used in the Japanese art of kintsugi, creating an adhesive used to repair broken pottery.

When creating the Lycurgus Cup, a glass chalice featuring a depiction of King Lycurgus of Thrace, Romans showed that using gold nanoparticles in decorative glass causes the glass to appear in different colors when reflecting light at various angles. The chalice presents both green and red.

“When you make gold very small—into nanoparticles—it changes how the material interacts with light, moving the absorption from blue to infrared,” said J. Daniel Gezelter, professor of chemistry and biochemistry and senior associate dean of education and undergraduate programs in the College of Science. “Depending on the size of the gold nanoparticles, you can tune where they absorb light and get different colored solutions.”

That ability to absorb light, particularly in the near infrared, makes the metal uniquely interesting to researchers looking for ways to target and treat disease, including cancer.

“Living tissue is nearly transparent (in the near infrared), so we hope the nanoparticles can be used for diagnostics, particularly with cancer cells,” Gezelter said. One of the big ideas is to functionalize gold nanoparticles to attach to cancer cells. Because tissue itself is nearly transparent in this part of the spectrum, the gold stands out.

When illuminating these particles with concentrated light, “those particles can transfer a lot of energy,” Gezelter said. “They will transfer that energy as heat to the cells where they are attached, potentially killing off cancer cells,” a process known as photothermal therapy.

In controlled environments, gold can last forever. But reduced to micro-thin levels, gold leaf is extremely delicate—vulnerable to wind, rain, even particulates in the air.

A job with a view

Countless faculty, administrators, students, alumni, fans, and friends will cast their gaze to Mary and the Dome in their lifetime. None of them will get the chance to see the view from the top.

“This is exceptional,” Roesselet said. “We don’t have too many jobs that go up to 208 feet.”

“The view is great,” he added. “But we stay focused on what we’re working on.”

Before any gold is applied, Roesselet, Eide, and the team from Conrad Schmitt Studios conduct an inspection of Mary and the Dome, testing which cleaning techniques will be most efficient for the space, and which primer and sizing (adhesive) will provide the best bond.

The team selects the primer with the best adhesion to the cleaned substrate for overall application—two to three coats, depending on the surface characteristics, Roesselet said.

The inspection is followed by a thorough cleaning to remove dirt and dust and abrade the surface. Roesselet describes it as a controlled cleaning using standard spray bottles, biodegradable soap, and Scotch-Brite pads. The team gently removes any bumps or nicks in the previous layer of sizing caused by abrasives in the environment.

When driven by rain and wind, particulates in the air can be abrasive and have more of an impact than any kind of chemical reaction that could break down the primer and/or sizing.

Once they have a clean, smooth surface, the team uses an oil mordant gilding technique, which consists of applying an oil-based sizing. The sizing is left to set for at least 12 hours to create a sticky surface before any actual application begins.

“You want to build up that tack,” Roesselet said. Based on the temperature and humidity in the air, it sometimes takes longer. “After it achieves the proper tack, it’ll have an open time where it’ll still be tacky enough to gild over.”

Roesselet, Eide, and the rest of the team will be working with a “master roll” of gold leaf—a 4-inch-wide roll of tissue paper, 67 feet long, with 500 square gold leaves in each roll like a glittering roll of stamps—for a total of 20 square feet of gold. A thin layer of rouge powder, the same used by makeup artists, is applied to hold the gold leaf to the tissue paper.

Smaller rolls are used for touch-ups.

“Once we get into full gilding mode, you’ll be astonished at how fast the gold actually is going on,” Roesselet said.

Gilders carefully press each gold leaf into the surface, handling the tissue side of the paper only, layering the leaves to prevent gaps and fill in the ridges, seams, cracks, and curves of the primary surface.

“With gilding you’re actually controlling the paper that the gold is attached to; you’re not actually handling the gold,” Roesselet said.

Makeup brushes are used to smooth out the overlap and clean off any excess.

“We want something soft that doesn’t abrade it,” Eide said. At 250,000ths of an inch, gold leaf is so thin that even those makeup brushes leave a mark.

“Believe it or not, even with the soft brush, you have to brush (excess gold leaf) off in the same consistent direction or else those super-fine scratches that you create in the gold actually will be visible and will vary with the way the light is,” Roesselet said.

Both Mary and the Dome have their individual challenges. The detailing of Mary’s robes, her hair, the lines of her face are all spaces where the Conrad Schmitt team will need to watch for gaps and make sure they’ve got everything covered.

When they’ve moved on to the Dome, things get a little tricky.

Sizing can’t be touched after it’s been applied. Oils transferred from skin will impact the integrity of the sizing, attract dirt, and break the reflectance enough to become visible over time. For this reason, gilding the Dome is trickier. Getting in position is limited by both the surface and the scaffold.

When all is said and done, less than 10 pounds of fresh gold leaf will have been used to cover Mary and the Dome.

It’s been 18 years since the last regilding.

With a little luck and expert craftsmanship, it’ll stay gold for another 18 years.