Teaching English at Oakland High in the late 1990s, Ernest Morrell faced the age-old problem of how to get modern students interested in a canon of long-dead writers and poets.

“I just got tired of teaching the regular way that I was supposed to — it did not seem all that enticing or effective,” said Morrell, now the director of the Notre Dame Center for Literacy Education. “I think, more than being innovative, I was a pragmatist and realized if I wanted to get kids looking at me and not at the top of the desk, I had to do something different.”

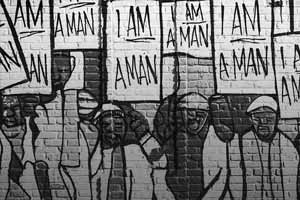

So Morrell and a colleague, who were both pursuing a higher degree, decided to introduce elements of pop culture such as rap songs into their classrooms as a way to engage the students with topics that kids know and care about. The goal was to start where they are and connect it to what they needed to learn, using hip-hop culture “as a bridge linking the seemingly vast span between the streets and the world of academics.”

They found the songs rich in imagery and metaphor, used them to teach concepts like irony and tone, and had students analyze their theme, plot and character development. Their students wrote papers comparing, for instance, the wasteland imagery in the poetry of T.S. Eliot with that of socially conscious early rapper Grandmaster Flash.

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (excerpt) T.S. Eliot

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

The Message (excerpt) Grandmaster Flash

I can't take the smell, can't take the noise

Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice

Rats in the front room, roaches in the back

Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat

I tried to get away but I couldn't get far

'Cause a man with a tow truck repossessed my car

They co-wrote a 2002 paper analyzing their pedagogy and results in a journal published by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). They wrote: “Hip-hop music should stand on its own merit in the academy and be a worthy subject of study in its own right rather than necessarily leading to something more ‘acceptable’ like a Shakespeare text. It can, however, serve as a bridge between urban cultures and the literary canon.”

Their work, Morrell said, was “noticed for all the right and wrong reasons,” ranging from a positive article in the Los Angeles Times to furious blowback in other circles. His colleague appeared as a guest on Bill O’Reilly’s Fox News show, where the host repeatedly excoriated multicultural attempts to “dumb down” education despite their peer-reviewed study of a positive impact.

That was the moment Morrell decided to fully pursue the academic route, launching his transition from high school teacher to literacy education expert.

“I remember going back to my professors and saying, ‘You need to help me pull together some research so that I can show that this stuff works,’” he said. “Then I got kind of hooked on it. I saw the power of academic research to really change outcomes and classrooms. And some of the things that we were fighting about on the Bill O’Reilly show are just common sense now.”

After stints at UCLA, Michigan State and Columbia, Morrell came to Notre Dame in 2017 as the Coyle Professor of Literacy Education, a professor in English and Africana studies, and director of the new center. Last year, he moved the work of the NCTE’s Squire Office of Policy Research in the English Language Arts to Notre Dame. That effort will kick off this fall with national studies of the hottest topics in the field: how popular culture and a concept known as translanguaging are impacting U.S. classrooms.

“We don’t want to throw really good research into the noise,” Morrell said. “But we do want to be ready because these are real answers for people — especially the digital literacies — that speak very poignantly to this moment of remote learning.”

Aspiring teacher

Morrell grew up in the San Francisco Bay area, mostly in Oakland and San Jose. He was the second of eight children to a mother who taught kindergarten and a father who taught high school.

“What I learned from them is kind of an approach to how one is an educator,” he said. “It’s a kind of a full-throated commitment to young people and their families, and a belief in the excellence in young people.”

After graduating from the University of California, Santa Barbara, Morrell turned down opportunities ranging from a graduate fellowship at Harvard Business School to a lucrative finance career with Bank of America.

Instead, he chose like his parents to teach “what you would call vulnerable populations.” His experience teaching English and coaching three sports, plus gospel choir, in the 1990s “definitely informs my research now,” he said.

Oakland High draws equal portions from a diverse community of Asian, Central American and African American populations in the area. Morrell said he still follows many of his former students on Facebook, watching their careers unfold as entrepreneurs, legislators, judges and more.

“It was really a chance to see the power of education for first-generation immigrants and those who were from the community that there’s a public narrative about — a real chance to, quote, unquote, make a difference,” he said. “And that was inspiring.”

Incorporating popular culture into the classroom felt natural to Morrell and Jeff Duncan-Andrade, his colleague at Oakland High. They would deconstruct hip-hop songs or have the students do a mock trial or make their own films. Neither thought it was a big deal at first, just a necessary means of grounding in the students’ world to draw their interest.

But after the L.A. Times story and O’Reilly show appearance brought recognition and controversy, both began to look more closely at their underlying reasons for doing so and at how to measure their success. Both were in the process of earning graduate degrees at University of California, Berkeley, so their classrooms became their research laboratories.

“That’s really where my research life got launched, just trying to think of ways to make it more innovative, more engaging, ways to get kids to see how their own lives were already filled with literacy,” he said. “Trying to make connections between those literacies and what happened in the classroom, and also to have the classroom be a space where those kind of out-of-school literacies were more highly regarded.”

Pop-culture academic

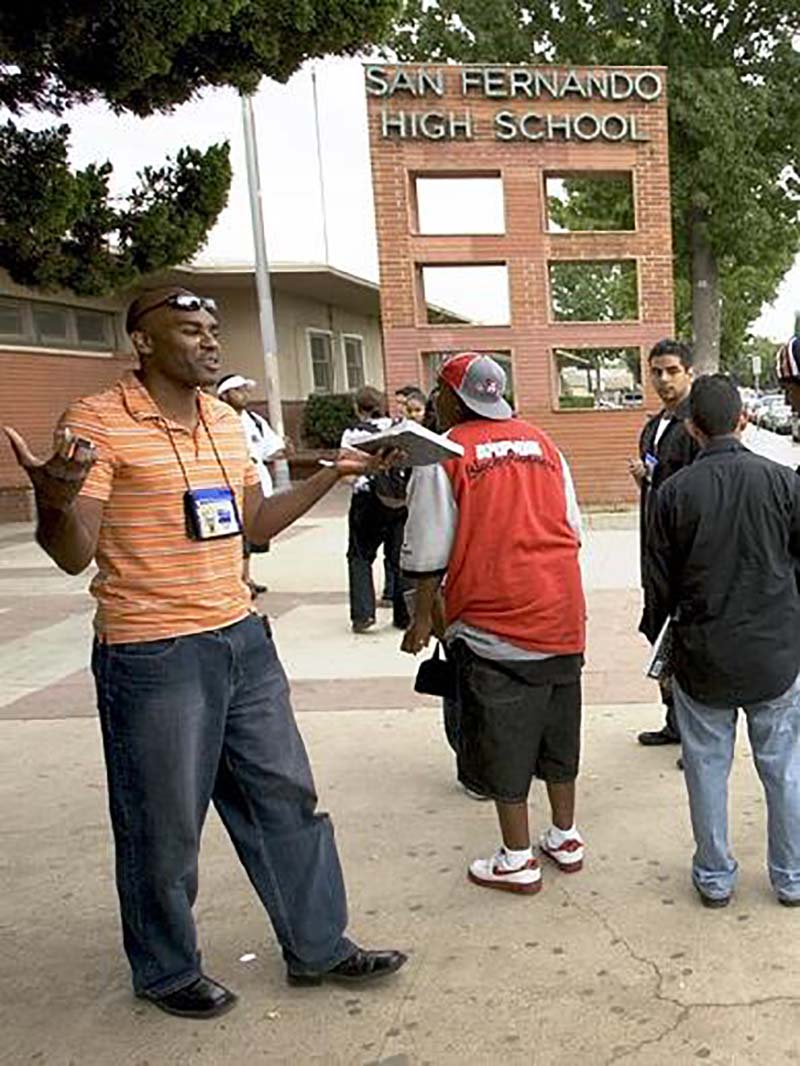

Morrell moved to Los Angeles in 1999 to complete his dissertation, and he began working as an adjunct faculty member and research associate at UCLA. Degree in hand, he joined the faculty at Michigan State from 2001 to 2005 while continuing some projects in Los Angeles, where he returned to UCLA until 2011.

During those years in L.A., Morrell pursued several interesting side projects that he does not view as detours. For about seven years, he founded and ran a record company called Desert Highway Records, which produced blues and folk music with the intention of keeping American art forms alive. Really, the endeavor fit his belief that popular culture is “where people tell really important stories about themselves.”

“English lit is always taking from what was once popular culture, but the intervening time is maybe 300 or 500 years, not anything immediate,” Morrell said. “I didn’t see the enterprise of music as being any different than what Homer was singing about in Greece.”

For about a dozen years, he also ran a seminar for high school students to become trained in how to do original research. Each project was headed by a class teacher along with a UCLA graduate student, looking into a topic that affected the students personally, such as school funding, neighborhood violence or dropout rates.

“They would learn how to conduct interviews, how to do field notes, how to distribute surveys,” he said. “They would design their projects, analyze their data, write it up as a formal research report, but they would also do a PowerPoint or documentary films, and we’d figure out how to take some kind of social action around what they’d learned.”

“I think, more than being innovative, I was a pragmatist and realized if I wanted to get kids looking at me and not at the top of the desk, I had to do something different.” –Ernest Morrell

That kind of work convinced Morrell that young students could be trusted to do complex academic work if the topic was compelling to them and they got the right training. Developing strong beliefs around students’ innate abilities also led to the final project: political advocacy.

Morrell came to realize that many of the important decisions about local education happened at the state level. The projects he’d been doing for about a decade repeatedly took him to the state capitol. So he decided to run for office in the California State Assembly. “I thought it might be an interesting path to pursue for educational justice,” he said.

He ended up pulling out of that campaign because in 2011 he was offered an opportunity to direct a historic literacy center at Columbia University in New York. The Institute for Urban and Minority Education has studied and advocated for how to improve the quality of life of urban youth through education for more than 40 years.

“It’s a big national stage,” he said. “If Michigan State was the infancy of my academic career and UCLA was the adolescence, then it was at Columbia I became a full-on adult.”

Urban Catholic

Morrell became more involved over the years with the National Council of Teachers of English, serving on its leadership board and as its president. He began to become more interested in Catholic schools and the intersection between Catholic and urban education.

In trying to figure out who was active in that area, Morrell quickly came across Notre Dame’s Alliance for Catholic Education (ACE) and its former director, Rev. Tim Scully, C.S.C. ACE trains top graduates to teach and places them for two years in underserved Catholic schools. What started as a correspondence turned into a friendship and eventually a serious conversation about conducting his research at Notre Dame. The idea for the Center for Literacy Education was born, and Morrell came to Notre Dame in 2017.

“Notre Dame is the intersection between scholarship and advocacy for justice and the Catholic mission,” Morrell said. “We really need to put forward, as Fr. John [Jenkins, C.S.C., University president] would say, ‘being a force for good’ through our research. We can show that this work — using our scholarly tools to advocate for the most vulnerable populations — is at the forefront of the Catholic mission.”

The NCTE’s Squire Office was undergoing a leadership transition when its first director, a Michigan University literacy expert, stepped down. The group asked Morrell if the Notre Dame center he runs would take over the work in May 2019.

And on the same day, Morrell was diagnosed with colon cancer.

The treatment process was a long haul, he said, but the Notre Dame community “made it a great place to be sick.” Between hospital visits from academic leaders and priests, support from colleagues and food deliveries from ACE friends, Morrell said he, his wife and three children received great care. He is happy to finally be in recovery and back to his life’s work.

Morrell and the Squire Office recently launched their latest efforts with two research papers about topics close to his heart. One is about introducing popular culture into the classroom, and the other concerns translanguaging, “one of the hottest buzzwords in the literacy world right now.”

Translanguaging starts with the idea that there are multiple linguistic registers used in students’ everyday lives, and these different types of language can be seen not as a liability, but from a positive viewpoint as a way to build multilingual practices and maximize learning.

For instance, students might speak informal and formal Spanish, as well as street and classroom English. They might switch between these four linguistic registers naturally, in the same way that Morrell used to notice Long Island residents change the way they spoke the closer the train got to New York City. Or the same way an author might switch between formal exposition and character dialogue in dialect.

Students read Toni Morrison in Morrel’s class.

“Yet these same students step into a classroom and see themselves as bereft of language,” Morrell said. “When really they’re more skilled at switching through multiple languages than many adults are. So how do you embrace that and leverage it in our classrooms?

“It’s really kind of going above this notion of individual languages, thinking about how a bunch of different language practices are fused together in the classroom.”

The shift from denigrating to embracing translanguaging has been “a real game changer,” Morrell said. Students and teachers are awash in language but haven’t always realized it. School districts with changing demographics or diverse populations, from L.A. to Texas to Florida, can benefit from this work that won the authors NCTE awards in research.

“Both of the studies are tremendously important because they show ability and skill where sometimes we haven’t seen it,” he said. “They challenge us to think a little bit differently about what formal instruction should be. And they help us to think much more democratically about the world we’ll inhabit.

“They’ll be in the hands of policymakers and teachers and education leaders who will have a real decision-making power over millions of kids’ lives.”