I knocked timidly—I was still new to the job. No answer, but the door was half open, and I had been told to go to this hospital room first: “She wants to hear Amazing Grace.” I walked in and recited my formulation to the tiny shape in the bed. “May I play some music for you, or would you prefer to rest right now?” She turned her head in my direction; a sound began in her throat but did not form into words. Confused, but not deterred, I lifted the viola to my shoulder and played. I played the hymn with all the skill, gentleness, and beauty that my conservatory training and countless hours of practice allowed. When the bow left the string and the last resonance returned to silence, I opened my eyes towards the woman on the bed. She had turned her head towards the window, closed her eyes, and breathed her last. Confusion and shock flooded me. I stumbled out of the room, past the arriving nurses. Did I do something wrong? “No,” the social worker, my supervisor, assured me. “She rode that song right up to heaven.” — Elaine Stratton Hild

Coda

Modern humans have an extremely vested interest in the end of life. Many are interested especially in extending the end. One study found American patients spend $18,500 at hospitals during the last six months of life, as tests, procedures and lengthy hospital visits all add up. Perhaps it’s a side effect of being alive at this moment in history, when faith in medical science is often well founded: Average life expectancy has been pushed into the late 70s or early 80s, double that in Medieval times. A lot of that is a testament to preventative care, to be sure, but there’s no question we have become increasingly adept at staving off the inevitable.

We have become, as Elaine Stratton Hild describes it, very specialized in the area of end-of-life care. “We are excellent at understanding the body, and how we can control symptoms, control pain,” she says. “On the other hand, because we’ve specialized in that, we’ve created some weaknesses in other areas.”

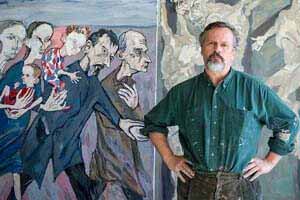

Hild is a musicologist who specializes in Medieval chants for the sick and dying. Her work is noteworthy for its scholarly contribution, but it may also yield observations that can help strengthen those “weaknesses” that exist in end-of-life care.

Hild was an accomplished viola player, accepted to the Cleveland Institute of Music conservatory at age 18. While studying there, the head of the music therapy department at University Hospitals of Cleveland approached Hild’s class to begin an experimental program in which the students would play for patients. It was on one of her first assignments that the poignant “Amazing Grace” moment took place. She continued playing for patients in hospitals and hospices until a diagnosis of focal dystonia — a neurological condition that causes involuntary muscle contractions — brought an abrupt end to her viola playing. (She now plays the harp, which does not aggravate the condition.)

“When I looked back at all of my hours of practicing and playing [viola] I thought, ‘What good was all that?’” Hild says. “I realized it was those performances in the hospital, those performances when I was able to offer comfort to the grieving family, or to offer peace to someone who was nervous at the end of their life — those were the meaningful performances, and that’s what made my practice and my playing worthwhile.”

So Hild directed her energies to learning music history, especially the kind of music reserved for people at the end of their lives. She said the experience of playing in those instances herself was overwhelming, but also positively challenging. What type of music would be appropriate for someone’s last moments on earth? What role could it play in emotional, even physical comfort at the end of life? In Medieval times, there were ready answers to these questions. The thinkers of the day considered music to be a kind of bridge between the seen and the unseen, the earthly and the heavenly. As such, music had an important role to play at the end of life.

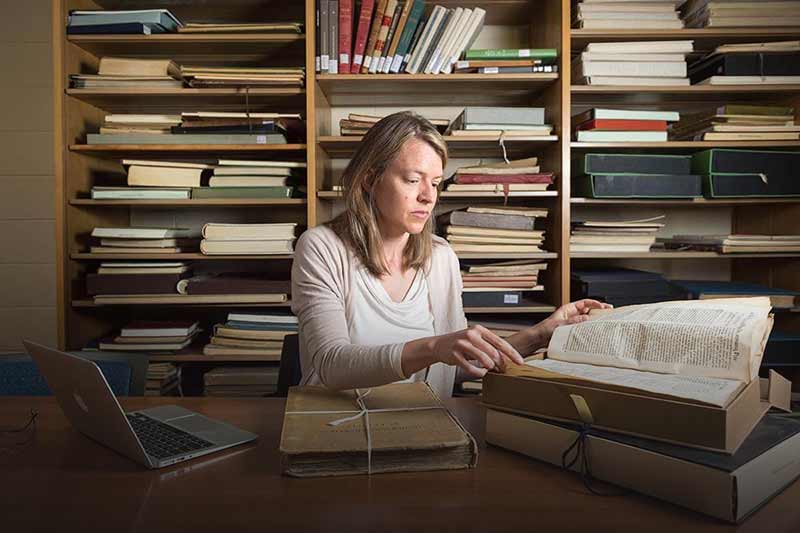

To learn these traditions, Hild traveled to Germany, to Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg. She learned Latin, and learned the notation used in Medieval manuscripts. She labored to find manuscript sources that might contain rites for the sick and dying, combing through catalog descriptions and traveling to engage with the manuscripts themselves. The work requires a certain blend of tenacity and patience. When she found a manuscript likely to have the rites, she examined it to find a certain notation indicating it was music, and if it was specific enough to reconstruct a melody. And then the output: transcribing the recoverable notations into a modern musical framework. It’s a skillset that is all but extinct. Hild estimates fewer than 100 people in the world can do it.

As one example of her findings, Hild explains how one chant for the sick communicated a layered scriptural appeal imminently appropriate for the moment: The piece starts with a call for Jesus to heal the afflicted pulled from Matthew chapter eight, then follows it immediately with a psalm that says, “Out of the depths I cry to you, oh Lord.”

“The psalm is lending some kind of intensity to the words of the chant,” Hild analyzes. “It’s as if you’re hearing that Gospel account with even more emotional understanding.”

It was a similar scene at the moment of a loved one’s passing. The community would have gathered around and sung a specific chant that commended their loved one’s soul to heaven: “Hurry, angels of the Lord, you who are taking this soul, and offering it in the sight of the most high,” the chant says.

In addition to the makings of an important historical and musicological contribution, what Hild found is a perspective on end-of-life care that is quite different from that of modern America. By our modern standard, Medieval medicine was at best rudimentary. At worst it was bizarre or macabre. It stands in increasingly stark contrast to advances in modern medicine that have added some 40-plus years to the average life expectancy in the Middle Ages. But in spite of our evolved understanding of the body and ability to extend life, Hild suggests there might be a knowledge gap that scientific advancements have created that wasn’t there centuries ago. Hearing is now understood to be the last sense a person loses before death. It is, as Hild puts it, the last form of beauty we can receive. And bringing it into a sterile hospital room may provide a warmer, human aspect to the circumstance, whether done for religious motivations or not, she says.

“We are overly medicalized at the end of our lives,” Hild says. “There was a movement in America to re-naturalize the birth process, and I think in this decade we’re more in the process of recovering the end of our lives from an overly medicalized model.”

Part of that recovery may be an acknowledgment of our mortality itself and the impact a death will have on a community of friends and relatives. Often end-of-life care includes a sort of isolation of the sick person, who spends valuable time in a hospital apart from loved ones. The Medieval model prescribed quite the opposite, the family gathering around the bedside to sing together. This created an order out of the chaos that aided both the afflicted and their support system.

“Imagine it,” Hild says. “When a group of people sing together, they have to breathe together. When we’re losing a loved one, sometimes it’s hard to breathe. Yet the community is forced to take a breath together, and to match their breath and their voices to one another. It joins the community together, and it’s something beautiful to do for someone who’s just gone beyond your reach.

“I wish we could recover some of that. Not that we need to sing Medieval chants, but at least we can see there is something that can be done.”

Hild came to the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study (NDIAS) as a residential fellow to create a book of the chants she’s pieced together through her research. It’s a scholarly pursuit, but also a personal one.

“That’s one reason I appreciate the Institute for Advanced Study so much, because they don’t need to draw distinction,” Hild says. “They’re looking for people who are doing academic work that can also make a contribution to contemporary society, so they respect the rigorous academic work that in itself is a type of calling.”

Through NDIAS, Hild joined a community of scholars that eschews disciplinary lines in favor of finding commonalities in individual research endeavors, and the mutual benefit those connections can yield. Hild admits a touch of surprise at the fascination among the fellows in regard to each other’s projects, and the implications one may have in another. She points to a seminar delivered by Tom McLeish, a professor at York University who focused on soft-matter physics and natural philosophy at NDIAS. As the presentation unfolded, a rich conversation developed as the fellows began to ask questions and apply the subject matter to their own fields of study. It’s a result, Hild says, of the naturally curious and approachable people NDIAS attracts.

There was another, perhaps greater surprise that arose from involvement on campus. Hild was approached by Jonathan Hehn, director of the Notre Dame Basilica Schola and the Gregorian Chant schola within the Notre Dame Liturgical Choir, who raised the possibility of a collaboration. Hild eagerly agreed. After a series of rehearsals, the chants Hild uncovered were performed as part of a concert in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart on April 29. It is believed to be the first time several of the selections had been performed in centuries. And while Hild notes the setting was a stark contrast from the Medieval bedsides where the songs were traditionally performed, she indicates that the painting “The Death of St. Joseph,” which adorns a southern wall inside the Basilica, made the environment fitting indeed.

“Again, this is something that happens at Notre Dame,” Hild says. “Because people are quite open and curious. When I came … I was quite sure I’d be sitting in my office doing the scholarly work. I did not know that I would be able to hear the chants performed at a high level. So it [was] a real unexpected surprise and gift.”

Hild often speaks of other gifts — the kind that the end of life can give us. A terminal diagnosis can prompt certain conciliatory conversations or important service projects that can yield fulfillment and a sense of wholeness. They can be, though perhaps not as often as possible, a chance to spend precious time with loved ones as well.

And that is another point at which Hild’s personal story and her time at Notre Dame meet. As her father neared the end of his battle with cancer, Hild and her mother and sister joined him by his bed. Hild chipped away at the NDIAS fellowship application while her father rested. He inquired about her work, asking, “Now in the Middle Ages, what would they be doing?”

On the day of his death, at the behest of her mother, Hild hit “send” on her application.

“It’s just one of these strange, amazing experiences that the last week of his life I was writing the application in the room with him,” Hild says. “It was just such a coincidence. He was asking about it, he was so curious, so whenever I’m here, I feel like I’m with him a little bit too.”

Produced by the Office of Public Affairs and Communications

- Writer: Andy Fuller

- Photographer: Barbara Johnston

- Videographer: Tony Fuller